How Latin Rhythms

Took Over The Sound Of Jazz

In my mind one of the most exciting parts of jazz history is when Latin music started to be combined with jazz in between the 1930s and 50s. There’s something about the rhythms joining forces with a big horn section and jazz harmony which really gets the heart pumping. From the early work of Xavier Cugat to the groundbreaking charts played by Machito and his Afro Cubans, there’s a lot of great Latin Jazz which has been created in the past century. Somewhat ironically, the style exists in a space where it is widely popular yet often misunderstood, with few western musicians actually knowing how to write or play the music authentically. And when you turn to the academic front, there is very little research being undertaken, resulting in many tertiary institutions continuing to push a simplified understanding of the music to students. Despite all of this, there are still ways to acquire authentic information about the style and my hope is that by creating this resource it can help others get a little closer to understanding Latin Jazz from a writing standpoint.

Somewhat surprisingly as someone that grew up in a white western family in the suburbs of Sydney, my journey with Latin influenced music started quite young. Back in 2003, as a 9 year old, my sister and I were in the car driving to the shops when she put on a new CD she had just bought from an unknown band called The Cat Empire. Being a kid, I really didn’t know anything about music but I do remember that at the time nothing I had heard on the radio or through my parents CD collection had really caught my ear. That all changed when my sister pressed play. Immediately, The Cat Empire became my first favorite band, and although I couldn’t articulate why I liked their music, something about their initial self-titled album resonated with me. Looking back on the experience, I’ve since realized that what drew me to the music was the integration of Latin music through the use of percussion, certain rhythms, and the irresistible montunos. Without knowing it, that album planted a seed which subconsciously informed my musical tastes for the coming decades.

After relocating to Melbourne due to my parents getting remarried, I found myself attending the local high school which just so happened to be known for its music program. I picked up the double bass and by grade 10 had officially entered the senior big band. With almost no experience playing any sort of jazz other than a few months of filling in with the intermediate band, the first chart that came my way was Maynard Ferguson’s version of Caravan. Like almost everyone that first hears the piece, whether it’s the original Ellington version or any one of the numerous arrangements that have since been written, I fell in love with the groove. Thanks to the director, he chose to fill out the rhythm section with additional Latin percussion and bring in specialty musicians from the Melbourne salsa scene to help us understand how to play the music. Looking back, I very much doubt we did it justice but importantly this was the first time in my life I had ever experienced hearing congas, timbales, and bongos, and I was hooked. There was something about playing with percussion that just felt better than anything else I had experienced thus far, a feeling I still have to this day. I still had no clue what was going on but my desire to learn more about the music was growing.

Fast forward a few years to 2012, I was finally out of high school and had just taken a leave of absence from an engineering degree in hopes of pursuing music as a career. My goal was to study jazz in the United States and when I searched for programs online, the first result I saw was the Manhattan School of Music. As YouTube had now developed a little further than being a place to share funny cat videos, I typed in MSM jazz and clicked on the first result. What I had stumbled upon was a video of Bobby Sanabria directing the MSM Latin Jazz ensemble which was playing Machito’s Wild Jungle. I was blown away. There’s not many times in my life where my jaw has hit the floor but this was one of them. I had never heard Latin music played like that before and it immediately became an all time favorite video. I tried transcribing some of it but still had no understanding about what was going on. However, unlike Maynard’s Caravan, this time around the music was a lot closer to the source and opened my ears to even more possibilities with big band Latin Jazz.

Thanks to the ridiculous price tag of tuition at MSM I decided it wasn’t worth applying, but I did end up looking elsewhere and was lucky enough to be accepted at the University of North Texas. Fortunately, UNT also came with a Latin Jazz big band as well as a specialty professor in the form of José Aponte, two avenues which I heavily leaned into during my time there. It was also where I fell in love with arranging thanks to colleagues like Drew Zaremba, Aaron Hedenstrom, and of course professor Rich DeRosa. For the first time in my life, I was at a point where I could actually learn more about Latin music from an authentic source and be able to apply that knowledge in my writing. Thanks to José, I was able to bring in a number of arrangements into the Latin band and see in real time the issues with the charts and receive feedback. It was an incredibly informative experience, but like many people in their early 20s, I convinced myself I knew what I was doing even when in reality I knew very little.

Years later I was able to bring José out to Australia for a week-long education trip where he worked with my youth program as well as a number of other schools. As it was the final project for the year, I decided to arrange a number of Latin tunes to feature José with the band. Unfortunately, this was single handedly one of the best and worst decisions I’ve ever made. Due to a serious lack of experience arranging Latin Jazz charts, other than the dozen or so I wrote back in college when José guided the percussion on what they should play, I really hadn’t spent any time learning more about writing Latin music authentically. As a result, when José came into the rehearsal with the youth band program, he called me out in front of the whole band. It was definitely embarrassing but what made it feel worse was the fact that everything he said was accurate and completely true.

In the coming months the world was hit by the COVID pandemic and like everyone else I was thrown into a neverending set of lockdowns. With all of my work now grinding to a halt, I decided to take the opportunity to learn more about Latin Jazz. I set up a call with José, who graciously gave me multiple hours of time and said to call him again once I had read every book on a three page list he sent me. What I realized was there was no easy way to learn about the style and no resource out there which nicely put everything I wanted to know together. I started going through his list and every time I came across a new piece of relevant information I added it to a word document. Eventually when the document grew too large, I started formatting it into a timeline, grouping information together based on styles and time periods. Eventually after working on it for 12 hours a day over the course of 8ish months, I finally felt like I had a loose foundation of Latin Jazz and how it came about. I scheduled a call with José and unlike our first call, we could now talk in depth about everything. While I had put in some serious research time, I still didn’t feel as if I really knew the content so I kept reading for another year or so and refined everything I had come across. Over the span of two years I had scoured everything I could and finally felt like I had exhausted every source written in English. It was a great feeling to finally be somewhat confident and know the inner workings of many different Latin styles as well as understand how they related to one another and evolved into Latin Jazz.

Like most things in life, this period of serious research revealed so many avenues and the more I learned the more I realized how little I knew. While I now feel considerably more knowledgeable, there is so much more left to learn, including centuries of folkloric traditions which really form the backbone of all of Latin music. The reason I’ve spent such an extended portion of this introduction telling you about my story, is because I hope it will give you an idea of how I came about the information written in this resource. I am not from a Latin American background nor am I a master of any Latin American styles of music. I’ve simply been an onlooker who has loved this type of music since I was a kid and have tried to learn as much as I can about it. This resource was created to be a starting point for people like me, offering invaluable knowledge I wish I would have known at the start of my journey. However, it doesn’t cover everything and is focused purely on the interactions of Cuban music with America, the core of how Latin Jazz was created.

In order to fully understand the scope of Latin music, a deep dive into the cultures which created the style is necessary. But to do so would mean covering over 500 years of music history, covering aspects from Africa, Europe, and the Americas. When you think about how much is usually covered in the average music degree, this sort of exploration would of course take many more years to cover everything adequately. Naturally, that means there will be times in this resource where we jump into topics where the background information isn’t as thoroughly explored as other entries I’ve written. Eventually, I hope to create future resources to expand the scope of this particular topic once time allows.

For this particular resource, my goal is to provide a foundation of knowledge so that others can feel confident in emulating the sounds of the great Latin Jazz bands of the 20th century, within reason. Unlike other entries I’ve written which sit out on one specific style, Latin Jazz is somewhat special as it is made up of dozens of specific Latin styles which have merged with jazz. As a result, what you’ll find here is a culmination of those different styles, all explored through the perspective of when they began integrating in the United States. However, before we start exploring them it might be worthwhile to first define the term Latin.

What Is Latin Music?

You might be thinking, Toshi, I know what Latin music is. I’ve listened to it for years and can tell you exactly when a chart is Latin or swing or bebop etc. However, in this situation the term Latin is used equally alongside many other styles which is a problem. Latin music itself is unfortunately an incorrect style name as it is the same as saying American music or European music. All it does is generalize music from 33 different countries under the same banner. Of course to understand Latin Jazz in more detail this poses an issue as it is far too broad. Imagine trying to unpack bebop or hardbop and simply referring to it as American music. How would we differentiate those styles from bluegrass or rock, or any other music played in America? It would be impossible and in this case it is impossible with the term Latin too.

The term itself when used in a musical sense actually came about in the first half of the 20th century to describe the ethnicity of the musicians who played this kind of music in the United States. Over time it transitioned to become the generalized name for all Latin American music in a western context, which is where it still sits today. Prior to Latin though, the music was called rhumba, another generalized name which we will unpack further in this resource. However, the true styles which make up this type of music actually have names such as son, mambo, cha cha cha, bolero, rumba, conga, etc. For the most part they all originated in Cuba, the first port of call for ships to the Americas during European colonization. However, they are the result of mass creolization and come from a line of various African traditions which merged with Spanish culture.

These styles made their way into the United States through various pathways over the 20th century, establishing a foundation for Latin music to grow further and integrate with jazz. Eventually, this led to the creation of a hybrid style which was built around characteristics found in swing, bebop, and many Cuban styles, ultimately being called Latin Jazz. While there are many Latin American countries, each with their own unique music, Cuba played the largest role in defining Latin Jazz and Latin music as a whole in the United States. These days the term Latin Jazz gets used quite loosely and many people associate it with Brazilian styles such as samba or bossa nova, however for those that play the music professionally, Latin Jazz is often limited to the sounds of Cuban and Caribbean styles with jazz influences, with bossa nova and samba falling under a different label. Although it would be very worthwhile to also look into the amazing integration of Brazilian music into jazz that occurred from the 1960s onward, this particular resource will only be focusing on the Cuban influence in the United States prior to the 60s.

Early Integrations

The story of how Latin music started integrating into the United States actually dates back prior to the creation of jazz itself. Without going into too much detail, due to Cuba being the gateway for the Americas, cultural exchanges between many different colonies in the Americas began taking place in the first century of European colonization. However, in relation to jazz, the start of musical integration really began in the 19th century in the port city of New Orleans. At this time, Cuban musicians had started blending folkloric rhythms with classical music, creating what came to be known as contradanza and eventually danzón. Due to the connection between New Orleans and Cuba, the style made its way into the United States and was picked up by the American composers like Louis Gottschalk. Eventually, these rhythms became a mainstay in ragtime and heavily influenced Early Jazz, being called the “Spanish Tinge” by artists such as Jelly Roll Morton. I covered this particular integration in more detail in the Early Jazz resource but for the purposes of this resource what is important was the establishment of four key rhythms, the habanera/congo/tango, tresillo, cinquillo, and amphibrach in American music.

Decades later, in 1930 when hot jazz and sweet music were taking the United States by storm, the Cuban artist Justo Azpiazu and his orchestra visited New York and brought with them an arrangement of El Manisero (the peanut vendor), a popular Cuban song at the time. It just so happened that while they were in America they had the chance to record the song and ended up releasing it through the RCA Victor record company. Sales went through the roof and it was the first major Latin song to sell over a million copies in the United States. Thanks to the extreme popularity, many other artists started imitating the sound and quite quickly Cuban music etched a place in popular Western culture.

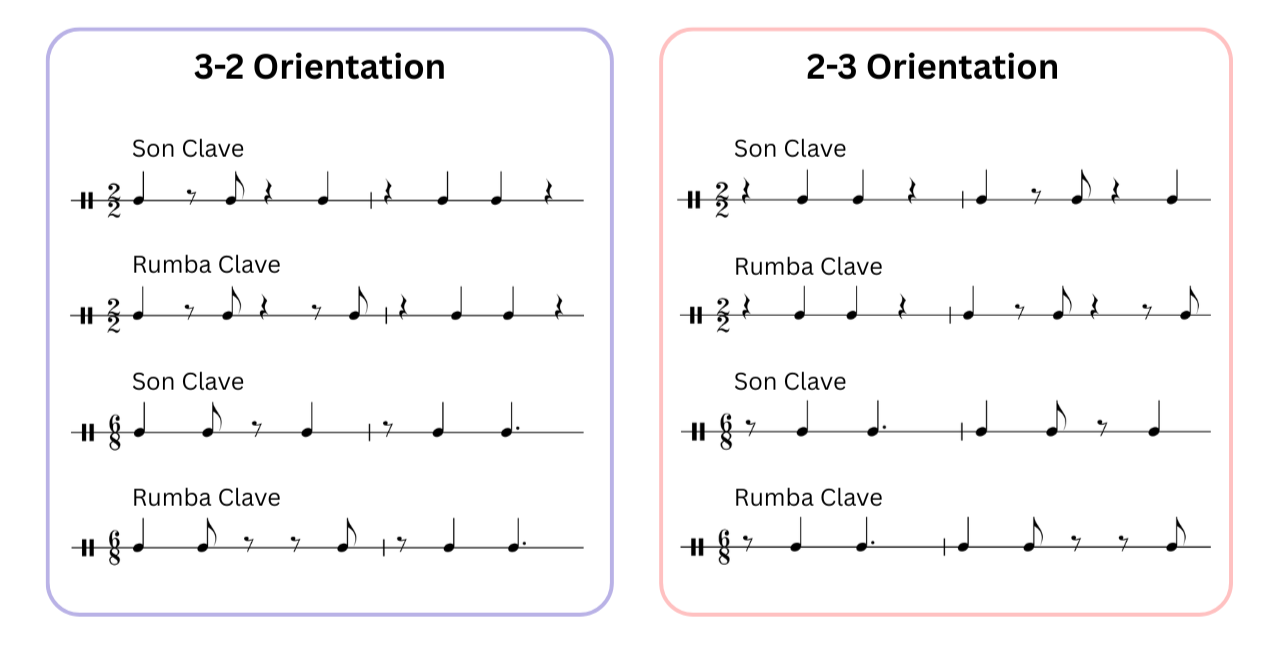

In order to understand what is going on musically in El Manisero, it would be wise to first unpack clave and how it functions in Cuban music. Unlike most European derived music which is built around a one bar phrase structure, the majority of Cuban music is felt in a two bar orientation. Like a metronome, clave operates as a time keeping device and informs which side of the two bar structure musicians are in. Similarly to how most Western musicians don’t perform with a metronome, clave is often omitted with the two bar orientation being implied through the rhythms played by certain instruments. In general, there are two popular clave variations: son and rumba. Both have a similar origin but over the last century they have been used with different Cuban styles. For the most part, rumba clave is used for anything that is more strongly linked to Afro-Cuban traditions such as rumba and conga, while son clave is used with almost every other style like son, bolero, guajiro, guaracha, mambo, danzon, cha cha cha etc. Regardless of which variation of clave is being performed, all options differentiate the two bar feeling through the use of a 2 side and a 3 side.

The primary difficulty with Cuban and Caribbean derived music is that there are a wide variety of rhythmic cells which are used, each lining up with clave in a certain way. The simplest to understand are those that are deemed clave neutral. In other words, these are one bar long rhythms that can be played on either the 2 or the 3 side with no issues. We’ve actually already looked at four of these rhythms, specifically the habanera/congo/tango, tresillo, cinquillo, and amphibrach. Where things start to get tricky are the two bar rhythms, often associated with various percussion instruments. As many of these rhythms are linked with certain styles, instead of unpacking absolutely everything right now, when a new rhythm is introduced throughout this resource I will make a note of its clave direction and the instrument that typically plays it.

In the instance when a rhythm is used incorrectly it is often called being cross clave. For example, if you had a two bar pattern that implies 2-3, it would be incorrect to play it in that orientation alongside a 3-2 clave. Naturally, when you start out you are inevitably going to do this by accident. The best way to fix your mistake is by seeking guidance from someone from the Latin American music community. Like most situations in life, after you have spent some time with these rhythms and understand how they relate to clave, you’ll be able to hear the clave direction being implied in the music.

Getting back to El Manisero, what we can hear in the track are a few key characteristics of the son cubano style. First of all, there is the instrumentation of vocals, a rhythm section with a harmonic instrument, in this case piano, joined by bass, bongos, and two secondary percussion instruments in the maracas and clave, as well as a couple of horns with the trumpet being the most important. While we may think the norm is to have congas and timbales, during the first half of the 20th century, son was purely associated with the bongos. The form of the song is also built around a repeated two bar section (which would later be known as a montuno section), with a brief verse from the vocals as well as improvisation from both the singer and trumpet player.

Looking at the specific patterns each instrument has been assigned, there is a 2-3 son clave pattern being played on the claves (the instrument), a bass line built around the tresillo, and another clave neutral rhythm in the maracas. In the piano part, the left hand doubles the tresillo bass pattern and the right hand plays a simplified cinquillo. Finally, the horns play a two bar variation of the cinquillo, taking the original clave neutral rhythm and making it now imply a 2-3 direction. As the bongos are the only major percussion instrument being utilized, they are free to improvise in response to the trumpet and vocalist, as well as any dancers who may accompany the music.

El Manisero

Justo Azpiazu

Although Azpiazu’s version of El Manisero is only one example of son cubano, it does demonstrate many of the core components of the style and represents the overall sound quite well. When it was initially released in 1930 it was labelled a rumba fox trot, a style marking which tapped into the emerging trend of associating Cuban music with the word rumba. Sometime afterward, the spelling of rumba changed to rhumba when marketing Cuban music to the American public, but instead of being associated with the specific Afro-Cuban style called rumba, rhumba represented all Cuban music that became popular in the United States. In this case, El Manisero was seen as rhumba as well as many other Cuban styles such as bolero, guajiro, guaracha, and son montuno.

A few years after the release of El Manisero, another band leader came onto the New York scene by the name of Xavier Cugat and took Cuban music to even greater heights. Having started his own Latin band in Los Angeles in the late 1920s, in 1931 he moved to New York with the opening of the new Waldorf-Astoria hotel. By 1933 he became the conductor of the hotel’s house orchestra and redefined the music they played, pulling from the music he grew up with in Cuba as well as many of the popular Latin styles of the time such as Argentinian tango. Under Cugat’s direction, the Waldorf-Astoria Orchestra quickly became known as the most popular rhumba band in all of America, and their recordings often went toe to toe with the top artists of the Swing Era. Unlike Azpiazu, Cugat blended Cuban styles with the sweet music of the 20s and 30s, taking the Cuban rhythms and integrating them into the classical model established by the orchestra prior to Cugat’s tenure. As we can see, the result was highly successful and led to Cugat getting to work with a number of artists including the likes of Frank Sinatra, Dinah Shore, and Bing Crosby, as well as collaborating with leading composers such as Cole Porter on tunes like Begin The Beguine.

Listening to his hits from the 30s and early 40s such as My Shawl, Perfidia, and Begin the Beguine, all three have pretty much the same rhythmic accompaniment as El Manisero. There is a bass playing either a tresillo or habanero pattern, an improvising bongo, clave being played by claves, and maracas playing the same clave neutral rhythm. The melody, harmony, form, and tempo are all completely different, but the pieces feel quite similar due to the same rhythmic accompaniment.

Sometime in 1936, Cugat witnessed a young Cuban immigrant living in Miami sing and perform on congas. He was so impressed by the musician that he offered him a job in the Waldorf-Astoria Orchestra. What he didn’t realize at the time was that this particular teenage boy would actually have a tremendous impact on American popular culture and help elevate Cuban music even further in the public sphere. Many know him today thanks to the television show I Love Lucy, but prior to becoming a celebrity, Desi Arnaz actually got his start by playing with Cugat. Born in Cuba in 1917, his stay in the country was cut short thanks to his father’s role in politics. When the Cuban government was overthrown in 1933, the entire Arnaz family was exiled from the country, leading to their relocation to Miami. Shortly after, Arnaz was picked up by Cugat and placed on a trajectory which would eventually lead to him becoming a household name around the United States.

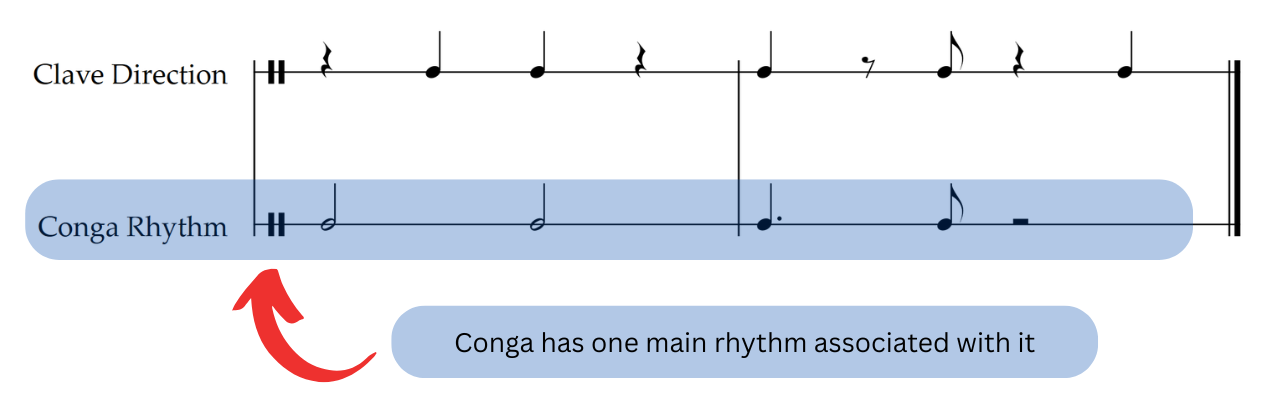

Thanks to the popularity of Cugat and the Waldorf-Astoria Orchestra, Cugat decided to branch out and run multiple bands under his name across the country. Due to the inability to be in more than one place at a given time, he made the most of the general public not being familiar with his appearance and hired other Latin Americans to fill the role. In 1937, Arnaz was booked for one such position for an event in Miami Beach on New Year’s Eve. Cugat was meant to send a band during the week, however in reality, five white musicians unfamiliar with Latin music showed up hours before the gig. Faced with a major issue, Arnaz had to think fast and drew from the music of the Cuban street parades he had heard as a child. Having witnessed how the parades could last for multiple days over the same rhythmic accompaniment, he quickly instructed the musicians to repeat a certain two bar pattern, allowing him to sing over the top and teach the audience how to dance to the rhythm. The specific style Arnaz had drawn upon was called conga de comparsa, or conga for short. Instead of worrying about the many layers of intricate percussion parts, the only rhythm that Arnaz chose to highlight was from the bass drum, which makes up the core of the groove.

While you may not be aware of the conga de comparsa style, it is quite likely that you are aware of the dance known as the conga line which accompanies the music. Based on Arnaz’s own words, it was at this particular event that he introduced both the conga line and the conga to American audiences for the first time. However, in reality it was probably a bit more complicated than that, with the style already having been played in New York and in other parts of Europe in prior years. To Arnaz’s credit though, he was definitely the main person to champion the style, which stuck with him throughout his entire career. Somewhat ironically, Arnaz’s father had been part of the government regime which had outlawed the display of Afro-Cuban music and culture in Cuba, including the very street parades that featured conga de comparsa. This lasted until 1938 when the parades finally were considered legal again. So while Arnaz was making the style become popular in the United States, the original musicians associated with the parades in Cuba were not allowed to perform.

A great example of conga being integrated into American music is the track Uno, Dos y Tres written by Rafael Ortiz. Recorded by Cugat in 1939, his version uses the iconic conga rhythm as the foundation for the entire arrangement with the melody and bass line featuring it throughout. At times other elements of the authentic conga de comparsa are used such as certain cowbell patterns and an accompanying conga part (this time the drum not the style).

Eventually Arnaz departed from Cugat’s band when he landed a major role in a broadway musical called Too Many Girls by Rodgers and Hart. Supposedly he convinced the musical director about incorporating conga into the music but as no recordings of the show exist we will never know if this is true or not. Fortunately for Arnaz, the production was a hit and led to a film being produced in 1940, his first major movie deal. As a result, Arnaz moved to California and brought the conga with him where it started to influence other Hollywood movies. One such example was a movie called Strike Up The Band, which featured Judy Garland singing a song by the name of Do The La Conga, a clear reference to Arnaz and the style. From there it was only a short time before he teamed up with Lucille Ball and became famous through the show I Love Lucy.

By the 1940s, Cuban music had well and truly become a major part of the Western music landscape, whether it be in Hollywood movies, on Broadway, or through hit records by the likes of Xavier Cugat and the Waldorf-Astoria Orchestra. However, none of these instances had the music blend with jazz. The closest it got was perhaps the instrumentation of some of the recordings which utilized a big band horn section, but the music itself was always closer to sweet music or the original Cuban styles themselves. That all changed in the 1940s though, when a certain musician broke from Cab Calloway to start his own band.

The Birth Of Latin Jazz

When looking back at the history of Latin Jazz, many people look at figures like Dizzy Gillespie or Stan Kenton, when in reality it was the result of one man named Mario Bauza. Like many of the characters we have explored thus far, Bauza grew up in Cuba where he played the clarinet. In 1926, he had the opportunity to visit New York while on tour and fell in love with what he saw, specifically the lifestyle of Harlem and the music being created by artists such as Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, and Paul Whiteman. With this one experience he promised himself that he would return and only a few years later he received a chance to do so.

The story of how Bauza made it to New York is one of those classic tales which becomes even more farfetched as the years go by. However, it is far too good not to mention here. In 1930, Bauza was presented an opportunity to come and record in New York thanks to the vocalist Antonic Machin, a member of Azpiazu’s band who was actually the singer on El Manisero that we looked at earlier. Due to unfortunate circumstances, Machin was in need of a trumpeter for a date two weeks away when he was talking with Bauza. Although Bauza was known as a clarinetist, he somehow convinced Machin that he would be able to play trumpet on the recording session. So within two weeks he picked up the trumpet and supposedly was good enough for Machin, granting him access to New York where he chose to remain after the session. Exactly how long Bauza had to learn the instrument nobody really knows, and it seems that Bauza may have experimented with the trumpet prior to his conversation with Machin. Either way, Bauza entered the New York scene in 1930 and started looking for gigs as a trumpeter.

A couple of years later, Bauza found himself as a member of Chick Webb’s band, an outfit that was seen as one of the best bands in New York at the time and had a prized residency at the Savoy Ballroom. Although Bauza had become a prominent trumpet player, he hadn’t yet mastered the approach to jazz articulations and phrasing. Fortunately, Webb was gracious enough to teach him exactly how to play in order to fit in within the New York big band scene. It was also during this period that Bauza was introduced to a young Dizzy Gillespie, who he took under his wing and let sit in on the bandstand from time to time. Eventually, Bauza left Webb and was hired by Cab Calloway in 1938, after a stint with Don Redman’s band as well as Henderson’s. It was during his time that he started to have the idea of implementing Cuban music within a big band setting, likely due to hearing Juan Tizol’s Caravan released by Duke Ellington in 1937. His fellow band members were not receptive to the idea, saying that the music he brought in sounded like some form of country music. However, Calloway entertained the idea enough to lead to the recording of tracks such as Yo Eta Cansa and Vuelva.

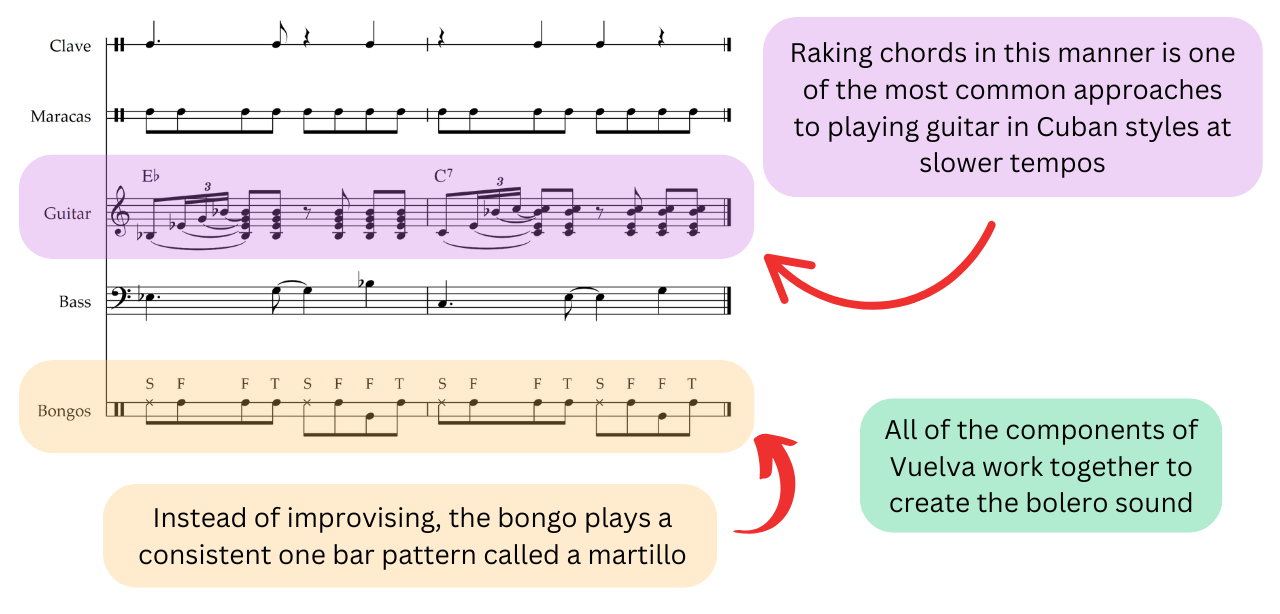

Looking at the tracks in more detail we can see that Vuelva builds off similar sounds to the rhumba tracks of Cugat, with a prominent tresillo bass line and clave pattern clearly being outlined. However there are a few notable differences, such as the use of the bongo martillo pattern instead of improvised interjections, a consistent eighth note/quaver feel in the maracas, and a guitar which rakes the first chord in each bar. These three elements all draw from the bolero style more so than son cubano, and showcase a slight difference in rhumba tracks from American bands.

Vuelva

Cab Calloway

On the other hand, Yo Eta Cansa departed considerably from the standard rhumba feel by building off a new variation of son called afro, short for Afrocubanismo, which had only been created a few years earlier in 1937. The style itself had a prominent rhythm often played in one of the percussion parts which can be heard quite clearly in the accompaniment behind Calloway. Another unique quality of the track is the use of an ostinato bass figure, something which broke from the classic son influence on rhumba and is clearly influenced by Cuban music more so than the common Latin hits of the day.

Yo Eta Cansa

Cab Calloway

Bauza’s story doesn’t stop there though and while in Calloway’s band he had the idea to form his own ensemble which would further blur the line between jazz and Cuban music. He called upon his brother-in-law, Frank “Macho” Grillo, to move to New York and help him put a group together, and after multiple failed attempts and Grillo’s nickname changing to Machito, the two finally started a successful band in December of 1940. They were known as Machito and his Afro-Cubans. Fortunately for the pair, in 1917 the United States had established the Jones Act which gave US citizenship to Puerto Ricans. As a result there were many Puerto Ricans living in New York who were familiar with the styles and rhythms of Afro-Caribbean music, providing the perfect base for the group. A year later Bauza resigned from the Calloway band and pursued directing his new ensemble permanently. To help merge the Cuban sound with jazz, he enlisted John Bartee, an arranger who had been working with Calloway at the time. While these tracks still sound exciting today, they lean more heavily into the Cuban rhythms with not much evidence of jazz being present other than the large horn section being utilized. A great example is Nague, released in 1942.

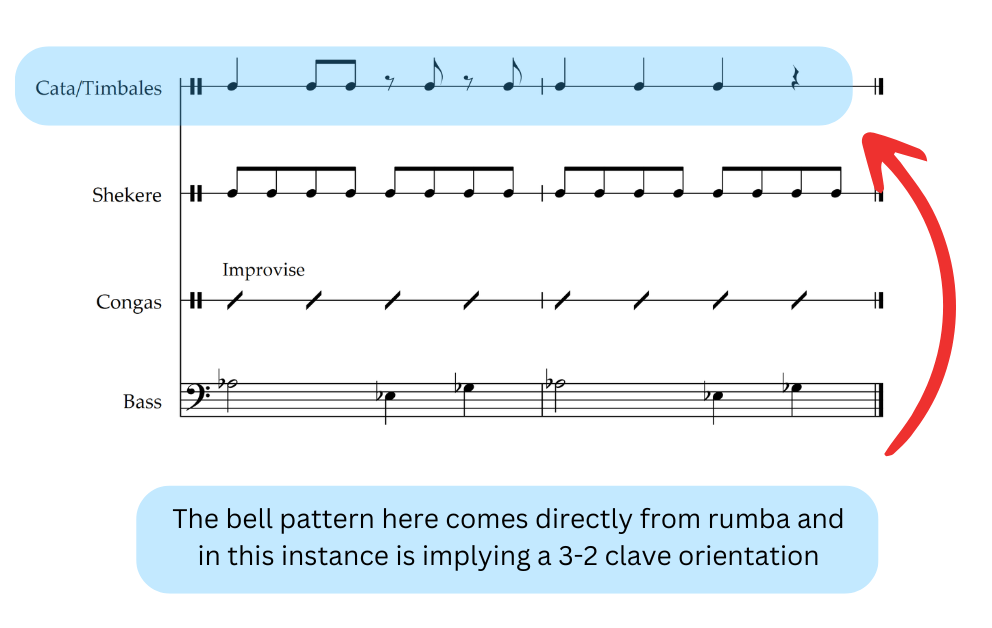

For the first time in the United States, Nague showcased Cuban music in all its glory as it was built on percussion rhythms from traditional rumba. For the most part, what can be heard on the recording is a consistent eighth note/quaver feel in a shaker (likely either a shekere or maracas), a bell pattern played on the catá (a hollow wooden instrument which sounds like a woodblock), an improvised part on the congas or bongos (it is hard to tell due to the recording quality), and a bass playing a simplified habanera pattern. What makes this track particularly unique is that the horns are being voiced based on the techniques used in the big band tradition as we explored in both the Jazz Age and Swing Era resources, providing a unique crossover between the two cultures.

Nague

Chano Pozo

At this point in music history it is important to understand that the percussion section of various Cuban music was often dictated by the specific style they were playing. For example, timbales were almost exclusively used in danzon, a more orchestral style, whereas bongos were associated with son. Due to the ban on Afro-Cuban traditions in Cuba, the conga had mainly been left to rumba which was played in secret, but once the restrictions were lifted it began to be incorporated into other ensembles. So at the time that Machito and Bauza put together their band, it was not common for all three instruments to be used together. At most, using the conga and either the bongo or timbales was normal, but all three had yet to be done. That was until Machito and Bauza united them in their ensemble. Thanks to the wealth of rhythms already associated with each of the percussion instruments, the congas, bongos, and timbales came together quite easily and merged many of their roles depending on the style being played. For example, the timbales would often pick up the bell patterns with either the congas or bongos playing a supportive pattern underneath the other improvising. If they were playing rumba, the congas might take a more prominent role whereas in son the bongos might solo etc.

Bauza and Machito didn’t stop there though, and reworked the place of percussion in the ensemble. Up until then, percussion instruments were often relegated to an accompanying role and were never given the spotlight. However, in Chick Webb’s band Bauza saw how he drove the big band with his drum kit and wanted to try to achieve the same effect with the timbales. When a young Tito Puente was hired for the Afro-Cubans, Bauza saw the opportunity to try out the idea and suggested the new approach to him. Thanks to Webb’s influence, Puente transformed the timbales into an energetic instrument which often led the whole band. It was so successful in fact, that it ended up becoming the signature approach for Puente for the rest of his life.

Like many, Machito and Bauza as well as other members of the band were drafted into World War II, leaving the band to stay stagnant during the war years. However, while away Bauza came up with the idea for a new piece which blended jazz more closely with Cuban music. Unfortunately, when they got back to New York the recording ban of 1942-44 was still in effect which delayed the recording of the track, but later in the 40s they finally were able to release Tanga. Unlike the previous recordings by the band, this track leaned into the influence of jazz improvisation and combined it with the Cuban styles they had been playing. The result was what many now consider the first example of Latin Jazz.

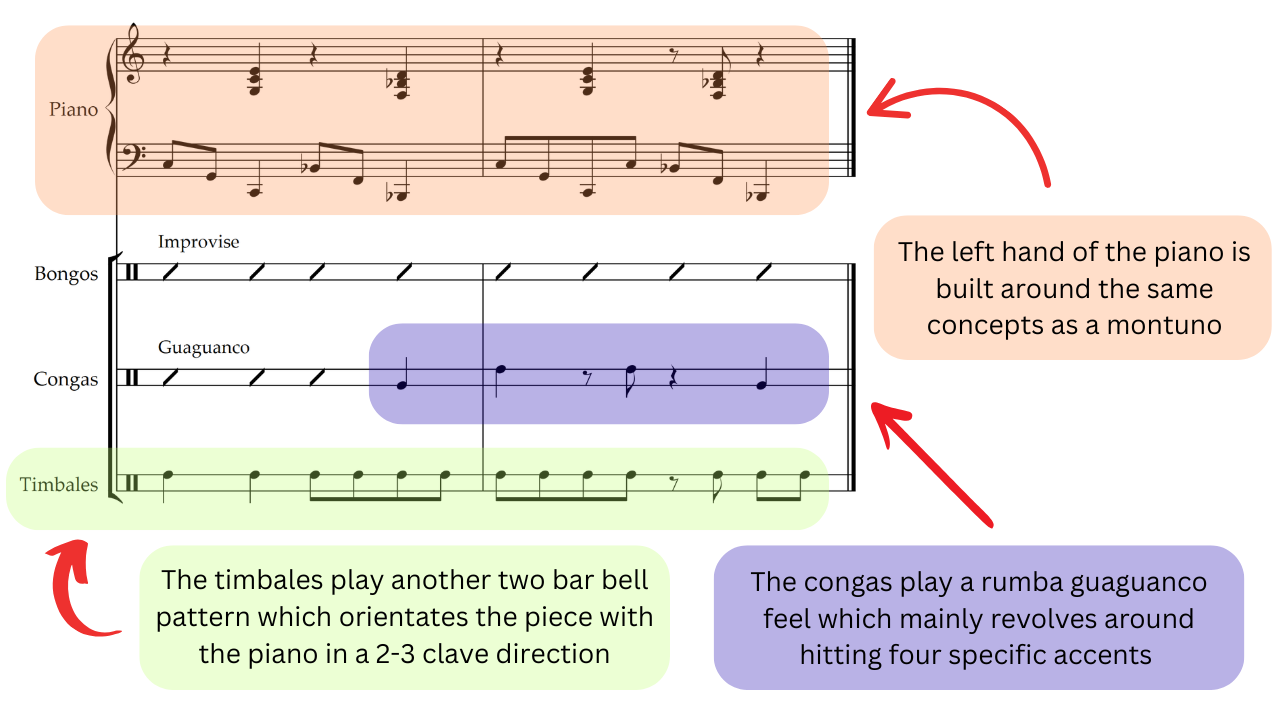

The basic foundation of Tanga was a repeated groove by the rhythm section with layered horns being used above. Unlike other pieces, there was no specific melody but about halfway through the piece a key change indicated the start of the solos. The rhythm parts were built off a mixture of ideas with the bass and piano drawing from son montuno, and the bongos, timbales, and congas drawing from rumba guaguanco. The end result is a mesmerizing sound which could last for days if necessary. The main part that differentiates it from other Cuban styles is the jazz influenced improvisation which takes place. Jazz harmony and articulations had already started to be implemented into Cuban music so all that was left was improvisation.

Interestingly, Tanga also shows one of the major differences between Machito’s instrumentation compared to the prominent swing bands of the era. The horn section is made up of trumpets and saxophones with no trombones in sight. The reason behind the choice was that Cuban bands in the 1930s and 40s didn’t really utilize the trombone, with the trumpet being the primary horn of choice. When big bands started being integrated into the Cuban music scene, for one reason or another the trombone was generally omitted with trumpets and saxes being used instead. Machito and Bauza would likely have drawn inspiration from these bands to some degree when putting together their own and the trombone wouldn’t become a prominent part of the sound until salsa was created.

Tanga

Mario Bauza

While it is hard to gauge just how popular the new approach was, we know that it at least had a big impact on Dizzy Gillespie. After hearing the Machito band for years, when Gillespie eventually went off and formed his own big band he knew he wanted to integrate some of the sounds he had been hearing. Thanks to the recommendation of Bauza to hire conguero Chano Pozo, Gillespie was the first American big band leader to push Latin Jazz to the same level as his fellow Cuban bandleaders. At first there were many roadbumps in the ensemble due to trying to implement congas into a band which primarily played swing music (a feeling which is absent in most Cuban music). To make matters worse, Pozo primarily spoke Spanish while everyone else were English speakers. After many complaints from the band everything smoothed out thanks to the shared language of music, with Pozo being able to teach certain interpretations through singing the parts.

One day, Pozo brought a new tune to Gillespie where he yelled out each instrument's name and sang a line for them to play. First the bajo, or bass, then the melody and on and on. The band’s arranger, Gil Fuller, madly transcribed the parts as Pozo sang them and the result was a tune called Manteca. Although it was a complete tune with all of the parts covered, Gillespie said it needed to have a contrasting section in the middle as well as accompanying chord changes. Fuller and Gillespie added a bridge to the tune and the end result was the first jazz standard written to clave. It was a huge hit and was the biggest selling record Gillespie ever had, and as such, inspired a whole generation of American band leaders to start incorporating Cuban elements, whether that be rhythms or percussion instruments into their bands.

What we hear in Manteca is a perfect hybrid of bebop, son, and swing all in one. The conga is primarily playing a repetitive figure called a tumbao, the bass is assigned an ostinato, the saxes are given a montuno like pattern, and the brass are playing a response. The bridge offers a moment of contrast, stepping into the world of swing with jazz harmony and a trumpet solo. Collectively, Manteca is a masterpiece which brings together so many fantastic elements of each style. At the time, Gillespie referred to it as a completely new style called cubop (cuban bebop), but with the passage of time, these days we mainly think of the piece as being an example of Latin Jazz.

Manteca

Arr. by Gil Fuller

By the end of the 40s, Latin Jazz had firmly been established in New York thanks to the efforts of Bauza, Machito, Gillespie, and a handful of other bandleaders. However, while this was taking place in the United States, Cuban music had continued to be developed, leading to the creation of mambo, a new exciting type of music. With such a strong link between countries, it was only a matter of time before mambo would make its way to mainland America, and when it did, it changed the landscape for Latin music entirely.

The Latin Predicament

Up until now we have mainly looked at the development of Latin music in the United States and how it inevitably led to the creation of Latin Jazz. However, we haven’t really looked at the components to capture the style in our own writing. That’s because Latin music in general is far more interwoven than many Western styles, at least when it comes to rhythm section parts. In order to understand the myriad of rhythms available to a percussionist at any one time, it requires a deep knowledge of many different Latin styles as they can draw from them all depending on the context. This can make understanding the characteristics of a certain style as well as trying to replicate them authentically in your own writing quite difficult. For me, it took months of listening and research to finally piece together the connections and unfortunately to be able to explain that succinctly in a number of paragraphs would be impossible.

But don’t worry, all is not lost, as there are often generic patterns that are quite accessible. The big takeaway I am trying to help you understand is that these rhythms aren’t always specific to a certain style, nor are certain styles restricted to only a few rhythms. As you explore the world of Latin music, you’ll start adding more to your list and make the necessary links between styles. For now though, understanding only a few will get the job done.

When looking at Latin Jazz, predominantly most arrangements come from the son style, and if you look back at the examples we’ve covered thus far, almost all of them have been built with this foundation. That’s because it is a highly flexible style which due to popularity, merged with almost every other Cuban style at the start of the 20th century. What made son so popular was the repeated vamp section associated with the montuno. It’s pretty safe to say that most people love montunos, and once they were introduced in son, they were implemented in almost everything else being played in Cuba.

Originally the montuno was simply an ostinato played on the tres (a cuban variation of the guitar), but eventually was transferred to the piano where it has stayed ever since. Unlike normal jazz comping where chords are played, montunos often take the fundamental harmony of a chord and spread out the notes over a syncopated rhythm. To begin with, the early montunos were simply off-beat notes, but as time went on they incorporated a number of different variations. These days, a montuno can take many different forms but what they all share is that they work over clave. Although it is common for a montuno to be prescribed to the piano, there is no reason it can’t be found on another instrument like the guitar.

Rico Vacilon

Arr. by Tito Puente

Alongside the montuno, there is typically some form of bass accompaniment which can be assigned to a number of different rhythms. Almost always the bass part outlined the root and 5th of a chord, regardless of the rhythm. As we have seen in the rhumba recordings of the 30s, the most common bass part was to play a repeated tresillo rhythm, however, a few other patterns are also acceptable. With the development of son montuno, a later variation of son, there was more emphasis given to syncopation resulting in the bass no longer accentuating the downbeat. These days, this type of playing is the most popular for Latin Jazz and can be heard almost everywhere.

Shifting gears to the percussion, this is when things start to get interesting. Originally the main Latin percussion instrument associated with son was the bongo who would generally improvise throughout a piece. There were however other secondary instruments such as the guiro, maracas, and claves which were utilized too, often playing clave neutral rhythms. For the most part, the claves would be assigned to the clave pattern, and the guiro and maracas would play a similar rhythm to one another. A great example of this sound is the very first example we looked at with El Manisero.

Eventually the other percussion instruments were added, creating a much more diverse range of options available for each instrument. Generally, the timbales, congas, and bongos, all drew from the rhythms of rumba and the folkloric Afro-Cuban styles, even though only the congas were utilized in that style of music. As such, the main concept behind the percussion parts was to create a sense of consistent eighth notes/quavers interwoven between all of the instruments. Over time, each individual percussion instrument started to be associated with a set of generic patterns which are often the basis for most Latin Jazz pieces today. Two of those patterns we’ve actually already come across. In Manteca the conga part plays a tumbao, the most popular conga pattern in both Latin Jazz and in Cuban music in general, and in Vuelva the bongos play a martillo, another common pattern. The one instrument we haven’t explored yet though are the timbales, which have a large variety of textures and rhythms associated with the instrument. The instrument itself generally makes use of two drums which include the skins and the shells, a variety of bells, often a woodblock, and even a cymbal depending on the player. Unlike bongos and congas, the timbales are played with sticks and are often given two different rhythms to be played at the same time. The most popular rhythm is the cascara bell pattern, a two bar rhythm which can be played on almost any texture on the timbales. Often the player will create variations of the pattern, leading to a more diverse part, which when paired with moving the rhythm around the instrument provides quite a lot of contrast from a single idea.

Now that we’ve established the basics for the son rhythm section parts, if you were to use any combination of the elements we’ve explored, you’d have a great foundation for a Latin Jazz piece. As I mentioned earlier, this is just a starting point and by no means represents the only options available in the son style, but should get you started if you are new to Latin music. Looking at the other parts, there is a considerable amount of freedom when it comes to melody, harmony, and rhythm when writing for horns. The main consideration is to make sure you are not going against clave. My suggestion would be to start simple with variations on the four clave neutral rhythms we started this resource with. Once you feel comfortable with that, the next step is to look at the two bar rhythms seen throughout this entry and try to use them. As there is already an established clave orientation with each of the rhythms, it will be easier to slot them in without confusing the clave direction. You can also get creative by removing certain notes from the rhythms to increase the variety in your writing. Eventually, you will start to see what works with clave and what doesn’t and you’ll be able to move on from using specific rhythms to craft your arrangements.

One other area which should be mentioned is the use of the drum set in Latin Jazz. For the most part, the three main percussion instruments were the core of the rhythm section but as time went on the drum set was incorporated into the sound too. Interestingly, the specific patterns played on the drums usually are directly transferred from the rhythms that are played on the percussion instruments. For example, bell patterns are usually played on the cymbals with conga patterns being used on the drums. With that foundation, other elements from jazz such as the backbeat merged with the vocabulary to create a hybrid approach. However, this fusion didn’t take place until much later and for the most part examples of Latin Jazz drum set playing emerged far later than the scope of this particular resource. During the 1950s though, one place it was witnessed to some degree was in hardbop, as we explored in that particular resource.

With a firm understanding of the basics, it is then time to start unpacking certain styles and what helps define their sound. Son is particularly flexible and is always a safe starting point, but other styles can have specific rhythms which have to be played such as afro, or must exist within a certain tempo range such as conga de comparsa or bolero. What you’ll notice is that as Latin music progresses through the 20th century, there is considerably more crossover between each style. For example, it is quite possible that on a given recording that the congas could be playing a pattern from rumba, while the bass is outlining a pattern from mambo, the piano is playing a montuno from son, and the guitar is playing a pattern from bolero, all the while other elements from non Latin styles are also being incorporated. At that point it becomes quite difficult to associate the piece with a given style, which as you can imagine is one of the reasons it is so hard to unpack Latin Jazz in a resource such as this.

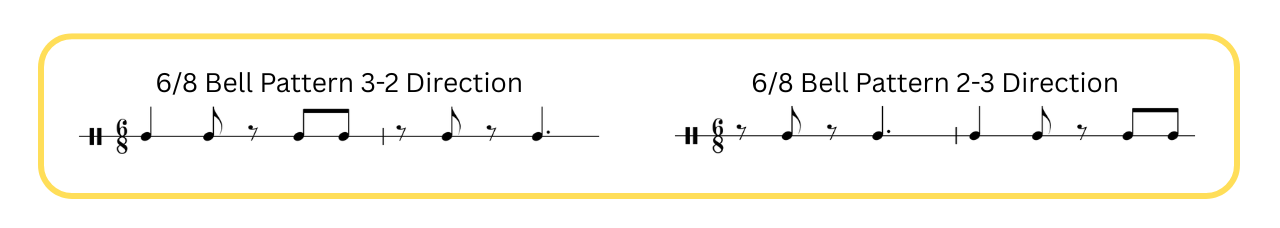

Now if you are a fan of Latin Jazz today, you may have noticed a major component missing from this resource, specifically the 6/8 styles. Unfortunately, these styles and the accompanying rhythms are considerably more dense than those that we have unpacked with son. In order to do them justice I would need to fully explore rumba as well as a number of other folkloric Afro-Cuban styles which would go far beyond the scope of this entry. However, I won’t leave you with nothing as they are such a fantastic part of the sound of Latin Jazz.

Instead of looking at the vast amounts of percussion grooves, we are going to focus on one specific element, the 6/8 bell pattern. Similar to clave, this particular bell pattern is used to help identify which part of the two bar orientation the music is in. In fact, it was actually where both the son and rumba clave rhythms were derived from, but that’s a story for a different resource. The main difference though is that it is only used in 6/8 time signatures. Due to being associated with dozens of different triple meter styles, the pattern itself doesn’t have a specific name. I was first introduced to it by a friend who called it a bembe, but since then I’ve realized that bembe is only one of the many folkloric Afro-Cuban styles the rhythm is associated with and is actually a restrictive term when describing the pattern. It’d be like calling the standard ride cymbal pattern the bebop or hardbop pattern, even though it is present in almost every jazz style. As the 6/8 bell pattern is originally played on a metallic bell, in Latin Jazz it carries over in the same capacity and is often played by the timbales. Unlike clave though, it is far more common to be emphasized which has led to the popularity of the rhythm in Western music.

Interestingly, when looking at the music of Machito, there are very few examples of the 6/8 feel being used in the recordings of the 40s, with most of the music being derived from other duple meter styles like son. However, there were definitely other Afro-Cuban specific recordings that took place in the 40s which highlighted 6/8 styles such as rumba columbia, they just didn’t make use of the big band instrumentation and generally captured the sound of the original style. On the other hand, in the 50s an abundance of Latin Jazz recordings made use of the 6/8 feel. Some leaned more towards the original styles whereas others only applied the 6/8 bell pattern. One great example is Chico O’Farrill’s Afro-Cuban Jazz Suite which he wrote for Machito and recorded in 1950. For a brief moment there is a section in 6/8 but it uses a different bell pattern than the standard rhythm we’ve looked at. Another recording is Tito Puente's Mi Chiquita Quiere Bembe from 1958 which prominently features the 6/8 bell pattern in the latter portion of the recording.

Latin Jazz represents one of the most exciting crossovers in jazz history, taking the sounds of jazz and placing them against the incredibly diverse rhythmic structure of Cuban music. Unlike any other style, it requires a considerable amount of knowledge on various Cuban and Caribbean styles, which when done correctly produces textures that are unable to be acquired anywhere else. The main aim of this resource is to introduce you to the style by looking at its development in the United States. Of course, there is much more to be explored other than what is written here, but in order to fully understand the amazing music of Tito Puente and Machito or the diverse list of artists from the 50s onwards, it would make more sense to first be familiar with a dozen or so Cuban styles. In future resources I plan to unpack Cuban music from an arranging perspective, providing the much needed context to not only understand what is being played but to capture the nuances in your own writing. But for now that will have to wait for a later time.

The Takeaway

Whether it be in ragtime, Early Jazz, sweet music, or in Latin Jazz, Cuban influences have played a significant role in the development of American music. Depending on the area, some styles simply applied Cuban rhythms and instruments in the form of Latin percussion, while others fully integrated both cultures together. For the first time in jazz history, the complex harmony was met with an equally complex rhythmic approach, which in my opinion has created some of the very best recordings in jazz history. To capture Latin Jazz authentically in your own writing is quite the task and is truly a life long journey filled with amazing moments of exploration and discovery. And the best part is that at every step of the way the music will keep inspiring you. I look forward to guiding you further in future resources on Latin music and hope this particular entry keeps you interested for the time being.