How To Capture The Sound Of

Early Jazz In Your Writing

As we slowly find ourselves inching further and further away from the origins of jazz, generally the idea of what Early Jazz is becomes simplified, with the truth being watered down or even becoming non-existent entirely. Now that innovations such as Bebop have taken place, it can be easy to look at earlier forms of jazz as rather simple and as such miss the true magic of what led to their creation. However, Early Jazz was a pivotal moment in American music and paved the way for everything that came afterwards. On a fundamental level, the style established many of the prevailing characteristics which still exist in jazz today. But maybe more importantly, Early Jazz was the culmination of the American experience leading into the 20th century, forged together by dozens of influences that crossed both class and race barriers.

Growing up in a typical Australian school jazz program, the last thing on my mind was the origins of jazz. I was too preoccupied with practicing and performing music to really care all that much about anything more than flashy technical lines and impressing my bandmates. It also didn’t help that the repertoire I played was a rather eclectic mix of big band jazz that mixed everything from Count Basie to modern European composers like Bert Joris, and that I was mainly listening to people like Michael Jackson and Stevie Wonder. While I had briefly heard of Louis Armstrong, I really didn’t know anything about jazz history, whether that be what it sounded like or how to play it.

After finishing high school I found myself flying to the other side of the world to pursue jazz in the United States. I was young, ambitious, and had no idea what I was stepping into but I was ready to tackle it head on. One of the components of my undergraduate degree was to take a jazz history class, the very first I had ever encountered up until that point and one that I was unsure if I’d like or not. Fortunately, the course was led by a masterful professor by the name of John Murphy, who was not only well-read but was able to provide useful commentary on pretty much everything we covered. It was in this class that I was exposed to names such as King Oliver, Jelly Roll Morton, as well as a myriad of other artists and significant events for the very first time. Murphy singlehandedly changed my entire view of jazz and that class really marked a turning point in my understanding of the artform.

Like most jazz history classes we began in New Orleans, the supposed point of origin for jazz. Due to the limited number of classes the semester permitted, we breezed through the Early Jazz period in a couple of weeks, but out of that time came one point which has stuck with me ever since. Murphy made a statement which I didn’t really understand at the time but has been reaffirmed with my own research countless times since. He said that jazz is commonly defined as European harmony meeting African rhythm, and that while certain elements of that statement are true it is a drastic oversimplification. Unfortunately, that specific class was only able to touch on a few points over a small number of classes, however it created a deep desire within me to pursue the area further and find out what really went down all those years ago.

It’s been close to a decade since I took Murphy’s class and within that time I’ve often deviated from my jazz history journey in order to focus on jazz arranging. With that being said, what I now realize is that those years focusing on arranging have actually put me in an interesting position where I not only can explore the history of Early Jazz, but can also unpack the components of the era to help others and myself recreate the music authentically. Since having that realization, I’ve spent the last few years researching a number of styles specifically from the arranging/composition point of view, all of which has culminated in this resource. My goal is that this document not only respects the origins of jazz but helps demonstrate the incredibly vast pool of influences that led to the artforms creation. Each of which showcasing prominent musical characteristics that came together in the late 19th and early 20th centuries through the performances and compositions of countless different artists.

As you can imagine, there’s a lot of information found here but it’s only the tip of the iceberg. One could easily spend an entire lifetime studying the history of each style mentioned or the solos and compositions of a small handful of artists covered, but in order to focus on common musical characteristics shared across multiple precursor styles and Early Jazz itself, I have refined the contents of this resource to what I think is the most essential knowledge necessary to recreate the sounds of the pre 1920 jazz era. Perhaps in the future I may unpack each style in more depth, but that is a concern for another day. Right now, let’s jump into Early Jazz and explore the many musical characteristics present!

What Is “Early Jazz”?

You may have heard the words “Dixieland” or “Trad Jazz” used to describe the early jazz music of New Orleans, however I prefer to use the title Early Jazz. Why? Well the word Dixieland, or more specifically Dixie, actually has racist roots in minstrel shows and I think we can all agree why it may be better to leave that word in the past. Over time Dixieland has been slowly replaced primarily with the title Trad Jazz, however both names are mainly used to reflect one particular type of music, typically defined by three horns up front collectively improvising. While we will explore that type of jazz to a degree in this resource, after spending a bit too much time with my head buried in jazz history books, what I’ve realized is that for the period prior to the 1920s, jazz really wasn’t defined by one singular style. There was no one type of music called “jazz,” instead there were many different styles played by a number of different groups of people split by class and race. Each of which eventually came together to create jazz as we know it today, and when that started taking place in the 1920s it began to be labeled as Hot Jazz.

After exploring a dozen or so different styles present in New Orleans at the turn of the 20th century, what I’ve realized is that a title such as Trad Jazz often implies a degree of simplicity to the music as it refines all of the components into a singular style marker. On the other hand, the term Early Jazz is in reference to the time period more so than a singular style and personally I feel it reflects the complexity of the era slightly better. As this particular resource is focused on exploring more than just Hot Jazz, to me it makes sense to think of this entire period and the music within it as Early Jazz.

The Cornerstones Of Jazz

One of the biggest issues that plagues any sort of history class is that there needs to be a start point on which to build from, however the reality of human life is rarely that simple. When we look at jazz history, the common jumping off point is New Orleans at the start of the 1900s. It is a logical place to begin but unfortunately by doing so we cut off so many of the influences that came beforehand. So often I have found myself asking why in these contexts. Why did jazz occur in New Orleans? Why at the start of the 20th century? As well as an almost infinite number of similar questions. As a result, in this resource I wanted to delve further and hopefully provide a musical link into the 1800s which helps explain where many of the characteristics of Early Jazz originated. Of course there is no end to this type of thinking and inevitably you could trace everything back to the origin of music itself, but for the sake of both my sanity and yours, I have tried to keep it logical and within the scope of characteristics that are directly related to Early Jazz. So where do we start? Like many, I think the best place to begin is with the African influence on American music.

The Birth Of The Blues

It is no secret that Early Jazz was very much influenced by African culture brought to America through the slave trade. However, so often it is refined to a few minor points such as blue notes and some kind of unique rhythmic language. But what is a blue note? And what are the miraculous African rhythms that seemed to be the missing ingredient to create swing? And can the influence of a whole continent filled with numerous cultures really be summarized in so few points?

To understand the African influence we need to understand the cultures that came to the Americas and how they integrated over centuries through forced slavery. There simply was not one African culture but hundreds, if not thousands or more, each with unique attributes and characteristics. Through slavery, many of these cultures were forced together as Africans were transplanted from their communities into plantations across the Americas where they often found themselves side-by-side with other Africans who spoke different languages, had different beliefs, and with the only similarity being that they had been sold into slavery from the African continent. Some African cultures had similarities based on the proximity to one another, such as the Dahomey and Yoruba people, however the original European slavers who brought them to North America didn’t care so much about their similarities or differences, and only cared about the profit margins their labor created.

Slavery looked a bit different depending on which European nation was enforcing the practice. The French were notably the most brutal on their slaves with horrendous reports coming from places such as Saint Domingue prior to the Haitian revolution (I’ll save you the graphic details but trust me it is truly disgusting to read). The British and Spanish weren’t far behind but did have slight differences to how they conducted their operations. This impacted how the African cultures interacted with each other and maybe more relevant to the influence of jazz, it impacted how much of the African culture persisted in North America in the early colonial period of the continent. Interestingly, the British would force slaves to learn and speak English and forbid any sort of African items or practices that may help the culture of their homeland linger on in the New World. In contrast, the Spanish allowed one day of rest and helped set up mutual aid societies to try and convert slaves to Catholicism, which backfired spectacularly and has since helped preserve African culture in places like Cuba for over 500 years.

By forcing the slaves to shed almost every part of their African identity, one of the only ways slaves in North America retained their culture was through singing. It just so happens though that singing played a large role in many African cultures prior to the beginning of slavery. The West African nations, where the majority of slaves to the Americas came from, had well defined vocal traditions with unique characteristics that varied to their European counterparts and helped introduce many notable aspects to the early American colonies. Notably, it is from these vocal cultures that we get blue notes, call and response, and a number of other characteristics which crossed over to Early Jazz.

These days blue notes are commonly introduced to musicians through the blues scale, however, this vehicle really doesn’t showcase just how impactful they were to American music a century or two ago. At the time when slaves were being brought to the Americas, Western music looked a whole lot different to today and the idea of incorporating the dissonances that blue notes presented seemed like an extremely radical idea. There were strict rules in place that had to be adhered to when writing music and as a result, the general public had grown to consider diatonic music in major and minor keys as the only acceptable form of the day. Blue notes went completely against this concept and as a result helped create the first truly American artform: the Blues.

Due to a lack of record keeping of West African cultures in the 1500s and earlier, the origin of blue notes is rather ambiguous. With that said, the modern theory is that they were a result of a unique type of harmonization present in that part of the world. While I have no knowledge of how to convey this approach through the original West African manner, I can represent the idea through modern day, European derived, music notation in the way I was introduced to it.

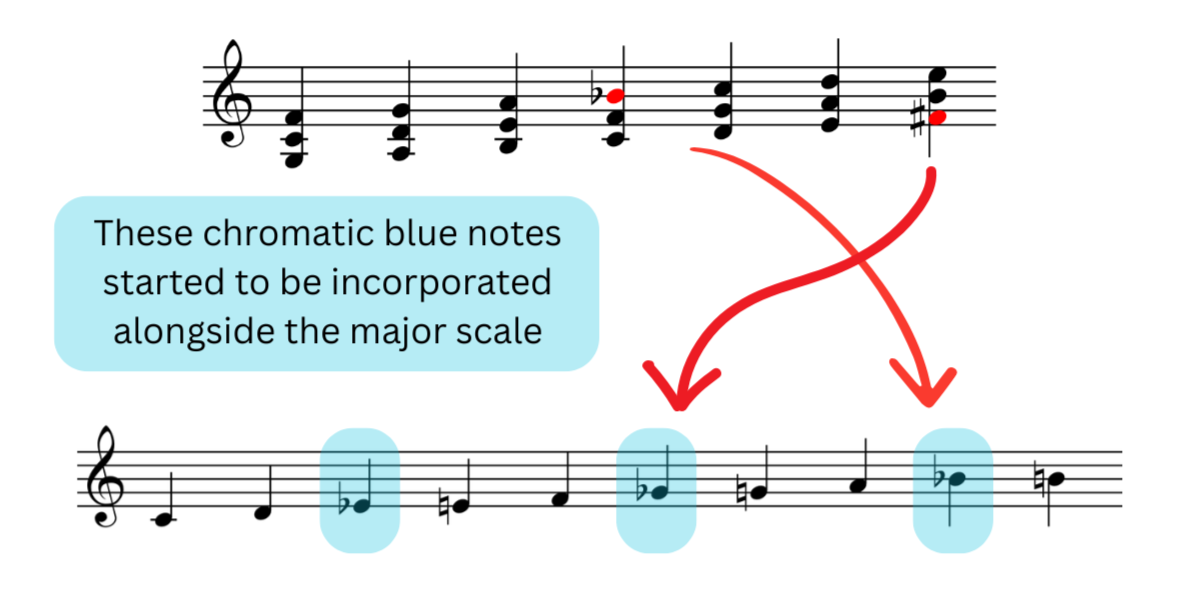

Unlike European music of the time, West African music primarily focused on singing alongside accompanying rhythmic instruments such as drums and bells. Although they did not utilize harmony in a manner such as the Europeans through accompaniment and chord progressions, they still did harmonize their melodies following strict rules. It is believed that they had certain scales, for the lack of a better word, in which melodies were written, some of which likely overlapped with European ideas such as the major scale. While the Europeans would emphasize a scale as having a fixed tonic which felt fully resolved (e.g. C in C major), their African counterparts placed equal weighting on every note with there being no specific “key.” Additionally, after establishing the “scale” with which to build a melody off, some cultures would harmonize the notes in parallel 4ths or 5ths, either above or below a given note (sometimes they would also do so with 3rds). As we know that at least one of the “scales” that West African cultures used is equivalent to the modern day major scale, we can map out the parallel motion to uncover the full range of notes one might hear. What we discover is that multiple notes outside of the “scale” start to be included and it is these particular notes that we consider to be blue notes. Specifically, blue notes can be thought of as the m3, b5, and m7 in relation to the tonic of a given key. For example, in the key of C major that would be the Eb, Gb, and Bb.

Due to African cultures not sharing the same harmonic preferences or rules as Europeans, all notes, whether dissonant or not, were considered equal to one another. As a result, it is likely that once slaves in America started being exposed to European music that they would have interpreted melodies through this particular lens and began integrating blue notes to create a “blues scale” so to speak.

Although blue notes likely came from some kind of African major scale equivalent, one of the more popular vehicles for melodies was the pentatonic scale, which is not only found in Africa but in many other cultures around the world. As slaves would have been highly familiar with the “scale”, the pentatonic scale naturally was used alongside blue notes and is how we get the blues scale today. Unfortunately, the modern blues scale doesn’t really showcase an accurate representation of how blue notes were utilized with the pentatonic scale in the early years of American history. Instead of simply running up and down the notes like how beginner musicians are shown these days, it was more common for there to be four note groupings that hover around a certain note. For instance, in the key of C two options would be A-C-D-Eb (6-1-2-m3) which would hover around C, and E-G-A-Bb (M3-5-6-m7) which would hover around G. Also very rarely would melodies jump more than a 5th.

It should also be mentioned that somewhere along the line blue notes would have been sung on top of some kind of diatonic chordal accompaniment, creating dissonances that were definitely outside of the realm of European music at that time. For example in the key of C having an Eb (m3) in the melody above an accompanying Cmaj chord. During this process, as slaves became familiar with the European approach to harmonization, the blue notes would inevitably have been organized into chords alongside the existing diatonic notes. While it’s hard to say exactly when the process took place, this is one of the major theories behind the creation of Blues harmony, specifically having I and IV chords with dominant qualities.

When looking at the West African influence, it can be easy to focus purely on blue notes as they are evident in jazz even to this day. However, the notes themselves were used alongside a number of other practices which were just as influential, one of which being call and response. While you may be familiar with this practice, in early African American music it was executed in a number of different ways. Typically, some kind of musical statement or question was raised by an individual (the call) which was then directly followed by some kind of repeat or answer by another person or collective (the response). In some cases a single person could also replicate both parts themselves. The call could be rhythmic, melodic, lyrical, or a mixture of the three with the response generally following whichever format was chosen.

Travelin’ Shoes

Performed by the Georgia Sea Island Singers

Alongside call and response, another popular melodic device was to use refrains. Instead of featuring a number of new melodies throughout a song, West African music often repeated the same melody line but with different lyrics. While this could be utilized as a standalone approach, refrains were also used in conjunction with call and response, which led to the establishment of riffs. Unlike refrains which were often multiple bars long, riffs were much shorter melodic fragments which could be repeated a number of times and often were sung over changing harmonies. Collectively, all three approaches became the staple formats for slave songs and have since permeated American music for more than a century.

Swing Low, Sweet Chariot

Performed by the Fisk Jubilee Singers

Travelin’ Shoes

Performed by the Georgia Sea Island Singers

It is no question that rhythm played a major role in West African music and similarly to the previously mentioned characteristics, the African approach varied considerably to the Europeans. When slavery first began, and for countless centuries after, the European approach was to feel music with either a big beat emphasis on the one of each measure or on each crotchet/quarter note. In contrast, the West African approach was to focus on the quaver/eighth note subdivision and view each rhythm as equal. Additionally, West African music did not operate in the same metered manner as European music, and could be thought of best as quasi polymetric (not just polyrhythmic) where each instrument played a unique repeated pattern with various accents. This is another case similar to the origins of blue notes, where the African approach used a completely different system to the Europeans and as such analyzing it with European derived tools would not capture the true nature of how West African cultures actually thought of rhythm. However, we can look at the impact that this view on rhythm had when it started mixing with European concepts in America but I’ll come back to that once we’ve covered a few more points.

With all of that said, there is one final characteristic to discuss: improvisation. Interestingly, while improvisation existed in West African music, it was far more rigid than what we see in jazz and definitely doesn’t seem comparable from a distance. A commonality between multiple West African cultures is that a drum would interact with a dancer or vocalist, but in most cases these would be prescribed rhythms that the musician could choose from. Due to there being multiple centuries between now and then as well as a lack of documentation, no firm claims can be made about whether improvisation existed to a greater extent or not, but if we look more closely at the African American experience, we can get a better idea of how it began to incorporate itself into the first slave songs.

By being restricted to plantations, it is likely that the early slave songs commented on everyday life and what they witnessed around them. There was also a level of embellishment that would have existed, with blue notes and other melodic devices being used to highlight an individual’s experience. In a sense, the life of a slave was one of improvisation, unable to return home and being faced with unprecedented daily challenges that were outside of their control. It’s not hard to see how that type of life would also be reflected into the music they created. Improvisation itself is definitely not only a trait of slaves as there are countless examples present in other cultures such as figured bass in baroque music, however this type of improvisation, one which is about improvising in order to communicate emotion to one another, does come from the African American experience.

So we’ve got blue notes, call and response, refrains, riffs, a different view on rhythm, and improvisation, what happens next? Well these are the core pillars which established the early blues. You may know it though as the work song, the field holler, the spiritual, or a dozen or so other names, all of which reflect various ratios and aspects of the characteristics we’ve unpacked as well as the locations in which slaves lived. I like to think of them all under the classification of “rural” blues as each slave community had their own experience and approach to music. Unfortunately, in the eyes of the white population, documenting anything about slaves and their music was not really seen as a priority (aside from a few select examples), so there is very little literature on the topic that still exists today. What we do know though is that in the first half of the 19th century when the minstrel shows began incorporating elements of African American culture to parody and humiliate, slave music was highlighted to some degree by white performers. However, it wasn’t until the end of slavery when freed slaves in the South (Texas, Mississippi, Louisiana etc) began relocating to city centers that a more formalized version of what we call the blues today started to form. It wouldn’t be until the 1920s when this new “urban” blues would get nationwide popularity with vocalists like Mamie Smith, but all of the characteristics we’ve discussed had been present for well over a century in African American music at this point and had already started influencing the start of jazz decades prior.

Backwater Blues

Bessie Smith

American Popular Music

When I first was introduced to Early Jazz the most common jumping off point was the blues, but after spending a bit more time with literature covering the 19th century I’ve realized that there are a number of other factors worth considering too. Blues did play a major role, and we will come back to it a little later, however it was only one type of music present in the 1800s. In the same century there were actually a number of more popular styles, well at least when it came to white audiences. All of them played a role in the formation of jazz and when it comes to replicating Early Jazz accurately from an arranging perspective, they are worthy of inclusion.

To understand the music of the 19th century we must first understand that styles weren’t simply associated with the color of someone's skin but also by class. For example, upper class white audiences were strongly associated with classical music and the variety of dance styles such as the waltz and polka. However as you travel down the economic ladder you see the popularity shift toward brass bands, minstrel shows, and a large variety of folk music. Of course there would have been some level of crossover between the music of different classes however it is clear that class played a major role in dividing musical taste among the population. Surprisingly, many of these staggeringly different styles of music all helped form the foundations of jazz.

One of the most popular musical formats of the time was brass band music. With the invention of the rotary and piston valved brass instrument in the first half of the 1800s, brass ensembles started appearing everywhere from 1835 onward. Almost all of the small towns around the country had one and thanks to the influence of various European countries, within the century these bands included a wide range of instruments from cornets to trombones, as well as percussion instruments such as snare drums and cymbals. The success of the ensemble came from the strong ties with the American military. After the American revolution, the national army was disbanded into local militias, each of which included a small number of musicians (typically a fife and snare drum). Over time they followed the shifts in military bands abroad and began integrating brass instruments. Before long, brass bands emerged everywhere and with them came a strong association with military music, at least initially.

Some of the notable compositions from the time include Hail to the Chief and The President’s March (Hail, Columbia), with the large majority of the repertoire being marches or hymns. Looking back on this repertoire the compositional elements are rather simple with most of the instruments playing the melody alongside some sort of plodding bass line with very little harmonization. This was most likely due to practical reasons to maximize the strength of the melody regardless of the skill of any one individual. In fact, it wasn’t until 1876 when David Wallace Reeves started assigning a countermelody to the trombone.

Hail To The Chief

James Sanderson

Second Connecticut Regiment

David Wallace Reeves

As all musical formats do, the brass band developed over the course of the 19th century, adding woodwinds and eventually transforming into the modern day concert or wind band. When this started taking place one name started to emerge as a prominent figure, John Philip Sousa. He was so popular with the American public that his recordings held the top spot for record sales, alongside opera star Enrico Caruso, until the emergence of recorded jazz starting in 1917. Adding to the list of well known marches, Sousa contributed a number of compositions to the medium, including Semper Fidelis, The Washington Post, and The Liberty Bell to name a few. He was also the one to commission a new type of marching tuba which ended up being named the sousaphone.

While marches were loved by both black and white audiences, they were only one component of the American popular music sphere. Another very important part of the 19th century was the minstrel show, a format which notoriously featured performers in black face who portrayed offensive caricatures of African American life. These days it is easy to see how this format was highly problematic, however it also established a set of common songs known across the country that surprisingly still live on to this day (minus the racist lyrics).

Prior to the invention of the automobile, the United States was mainly populated by small towns, each with its own culture and interests. Of course within certain regions there would be a large amount of similarities, however it was much harder for information to travel and as such there were very few nationwide trends when it came to music. Beginning in New York in 1843, the minstrel show ushered in a new type of entertainment which was able to link communities with one another through a shared experience. One which was repeated countless times all across the country. Unlike other stage entertainment which toured at the time, the minstrel show followed a set formula and had an associated set of songs and routines. Over time, regardless of the location you may have lived, if you had seen a minstrel show then you could relate to anyone across the country who had seen one too. In an era before recording technology, the minstrel show was the first medium to establish a unified set of popular American music, well with white audiences that is.

The format originated from northern working class people who sought to make themselves feel better at a time when immigrants, often people of Irish and Italian descent, were often discriminated against due to their heritage. Unfortunately, these immigrants followed the same behavior that the upper class had displayed to them but instead used it against the only class of people considered lower than them at the time, African Americans. By doing so, they created a form of entertainment that showcased black people in an unflattering light, associating them with negative traits such as being carefree and lazy. These portrayals were severely exaggerated and collectively established an extremely racist form of entertainment that lingered on for just under a century.

Music played a large role in minstrel shows, both accompanying musical acts as well as playing in between sets. To begin with, most of the music came from British or Irish sources but quite quickly that shifted to American composers as the medium grew in popularity. While there was a large variety of music at play, the most popular songs were often those associated with depicting African American life in the exaggerated manner discussed earlier. Often these melodies were quite catchy and came with an assortment of highly racist lyrics, and over time began to be referred to as coon songs. To this day, you’d be surprised just how many of these melodies still exist in pop culture. Some of the popular songs included Old Zip Coon, Oh! Susanna, Old Dan Tucker, Jump Jim Crow, and Camptown Races.

Oh! Susanna

Stephen Foster

The last pillar of American popular music was classical music, considered to be the music of the upper class due to its sophistication. The 1800s was known for the hits of the prior century, including those by Haydn, Mozart, as well as the emerging Beethoven, but also brought a range of new faces including Chopin, Ravel, and Debussy. Of course there were countless others too. In the world of opera Bizet’s Carmen became one of the biggest hits of the century as well as Lecocq’s La Fille de Madame Angot. Although this type of music was typically reserved for wealthy white patrons, the music would still have been recognizable to those in other classes. The 19th century brought with it the piano craze resulting in many households purchasing some form of piano. With the rise of instruments came a rise in published sheet music aimed at amateur musicians. Through this medium, classical music was no longer restricted to the concert hall and began being performed in households across the country as well as other popular styles.

Depending on the particular composer and decade, classical music of the 19th century could both be somewhat simple and follow conventional 18th century counterpoint concepts or be innovative and explore new harmonic ground. European harmony was redefined by the impressionist composers who took western music from strict major and minor keys to a realm outside of diatonicism. During this period we see sounds such as the diminished scale and whole tone scale be more thoroughly explored, as well many other non-diatonic patterns. All of which was being digested by the American upper class and reworked by a new generation of trained American composers.

Voiles

Claude Debussy

It is also worth mentioning that while the three major sectors of American pop music in the 19th century were brass band repertoire, coon songs, and classical/opera compositions, there were many more styles present throughout the country to a lesser degree. Due to the high influx of European immigrants, folk music from Ireland and Italy, among others, would have been played in the cities where ethnic enclaves were formed. There were also rural augmentations of the blues which inevitably transformed into bluegrass. However, while I personally find American pop music fascinating, there is a much larger point to be made by this section. All of these different styles had some level of influence on the formation of jazz, but to do so, they had to start merging with African American culture, a process that is called creolization.

The Melting Pot

Whenever someone asks where jazz originates from it seems like a no-brainer to say New Orleans. But what made that one city so special in comparison to all of the others? Well it was a blend of circumstances which just so happened to lead to the creation of jazz, but before investigating those events there is one thing that needs to be clarified. When looking at jazz history, specifically in New Orleans, the word Creole comes up quite a lot. Creole is generally used to describe the Afro Haitian people who blended French and West African cultures together and came to the United States after the Haitian revolution. Unfortunately, it’s also quite similar to the word creolization, which describes the process of two different cultures merging with one another. We will primarily be focussing on the latter, specifically look at the creolization that took place between black and white cultures in America due to the emancipation of the African American slaves. But don’t worry, the Creoles will get a mention too. Now let’s get back to New Orleans.

The history of the city is unlike any of the others in the United States. It originally was colonized by the French, but as the soil wasn’t able to generate the same level of profit in comparison to their other colony in Saint Domingue (modern day Haiti), the city was left pretty much untouched for the first years of its existence. Shortly after, a few major events impacted the French empire, namely the French revolution and the Haitian revolution, creating major instability and leading to the Louisiana territory being given to the Spanish temporarily. Although the Spanish only held onto the land for a few years, in that time they left a tremendous impact that forever changed the city.

One of the biggest shifts the Spanish implemented was a revised version of slavery. As mentioned earlier, the Spanish were known to have a slightly more relaxed approach to slavery compared to the French. That is to say, they gave slaves a day off on Sunday for religious reasons and allowed them to maintain some level of African culture. With the change in approach came a shift in how slaves operated in Louisiana and on Sundays large gatherings would take place where slaves could celebrate their heritage. Interestingly, once the French reclaimed ownership of the territory and then sold it to the Americans, this practice was maintained with a few restrictions. Instead of gatherings being permitted in multiple places, they were now limited to one area, Congo Square. As a result, the cultures of each slave nation present started to integrate with one another, creating a new unified form of African American culture.

Once the slaves of Louisiana were freed, many made their way to New Orleans, mirroring a national movement of freed slaves relocating to urban centers. As a result, African Americans started to impact the culture of these places and in New Orleans one way they did so was through music. In the previous section we explored a number of different popular American styles in the 19th century, however all of them were primarily enjoyed by white audiences (with some exceptions) up until 1865 with the abolishment of slavery. Now that African Americans were technically able to perform music freely whenever they wanted, the hundreds of years of African American culture that had been developing through slavery was able to integrate with the popular white music of the time. In New Orleans, this manifested in a few major ways, one of which being through brass bands.

Due to the brass band boom a decade or so earlier, brass instruments were easy to come by in the city. Instrument manufacturers had produced large volumes of new instruments and once African Americans were able to legally purchase them, the price was low enough that even a poor freed slave could afford to buy their own instrument. In order to survive in a world with no support networks for black people, African Americans in New Orleans formed mutual aid societies which helped look after members. After paying a registration fee, members were entitled to various benefits such as sick pay and funeral services. Each of the mutual aid societies had an accompanying brass band who would perform music for these funerals, and out of this tradition a new form of creolized brass band music was created.

When African Americans began performing traditional brass band music, not only did they have access to the wide variety of traditional marches already established, but they also incorporated their own repertoire of blues’ and spirituals. Additionally, the music was interpreted in a different manner allowing for a higher level of individual expression through embellishment. The result was a new style of music called second line, a name derived from the position of the band during a funeral procession. While there are many places in which black American music integrated with white music post slavery, second line ensembles were the main vehicle for African Americans to play music on brass and woodwind instruments.

During a typical funeral service, the second line band performed African American hymns to the church and then after the ceremony would accompany the casket to the cemetery by playing dirges. Once the burial had taken place, the band would play upbeat music, generally mixing blues, hymns, and pop songs. Some of the more popular repertoire for second line ensembles to play included songs such as Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, Deep River, Go Down, Moses, Steal Away, Nobody Knows The Trouble I’ve Had, Roll, Jordan, Roll, and Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child.

19th century New Orleans was not only a major destination for freed slaves, it was also one of the primary ports in the Americas being at the foot of the Mississippi river. Prior to the abolishment of slavery, it was common for ships from all over Europe and the Americas to dock at New Orleans, bringing with them a variety of different cultures. Due to the close proximity to islands such as Cuba and Saint Domingue, when the Haitian revolution took place, the city became one of the go-to destinations for Haitian refugees, also known as Creoles. Unlike African American slaves, the arriving Creoles with darker skin were considered free in the United States and collectively formed a new minority group within the city. Interestingly, many of these people were actually slaves who had escaped Saint Domingue due to the revolution but regardless of their history, they were welcomed as free individuals into New Orleans.

Somewhat ironically, this now free class of black Creoles adopted the culture of their previous oppressors and embraced the French lifestyle they had seen while living in Saint Domingue. As such, the Creoles dressed in eloquent clothing, played classical music, formed their own opera companies, and created a new black economic class. It is through this particular channel that upper class American popular music started making its way into black communities en masse. However, the Creoles also brought with them their West African heritage and the Afro-French culture that had been creolized in Saint Domingue. While there are many ways these cultures impacted the city, two noteworthy points include the importation of voodoo, one of the major religions from Haiti which was a creolized blend between the Dahomey religion and French Catholicism, as well as the Mardi Gras festival.

The Creoles were also one possible place where the “Spanish Tinge” started to interact with New Orleans culture. The term, coined by Jelly Roll Morton, is used to describe certain rhythms that originated from a variety of creolized cultures, all of which having some level of West African heritage. One place of origin could have been the Creoles as the African slaves present in Saint Domingue would have been familiar with said rhythms, another is in the African American slaves, and then one final option is through the Afro-Cuban influence. While we may never know which specific culture brought said rhythms to New Orleans, the fact that all three were present in the city means that it was likely that the rhythms were some form of common ground between each culture which led to their consistent use. However, as the term “Spanish Tinge” was primarily in reference to ragtime, I personally think that they came through the Cuban influence due to the composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk.

Considered almost unknown to most musicians in the 21st century, Gottschalk was one of the most popular American composers of the 19th century. He spent extensive time outside of the United States, and somewhere along the way was heavily influenced by Cuban composers and Afro Cuban folkloric music. Although Gottschalk wrote in a similar manner to other classical composers of the first half of the 1800s, many of his compositions make use of four key rhythms prominent in the Cuban Contradanza tradition. They include the habanera/congo/tango, tresillo, cinquillo, and amphibrach. There is no doubt that his music would have been heard in his birth city of New Orleans while he was alive, and most likely was one of the more prominent sources for the inclusion of these rhythms into the local music scene. Whichever way the “Spanish Tinge” made its way into New Orleans, it had a tremendous impact.

Ojos Criollos

Louis Gottschalk

In the second line world, the habanera/congo/tango rhythm was adopted in the bass drum part to create a unique feel called the Big Four. While it was no secret that African American music featured a more syncopated approach compared to white American music during the 19th century, the Big Four helped provide a shift away from the traditional downbeat heavy focus found in the common marches by emphasizing the fourth beat in a two bar pattern. As a result, it gave second line music a two bar lilt with a push into each phrase.

Additionally, African Americans began experimenting with using these same types of rhythms as well as a myriad of others, such as the 6/8 bell pattern, in their snare drum patterns. Over time this developed into a unique style of percussive accompaniment that also reinforced a two bar lilt and was highly syncopated in comparison to the more traditional approach.

Once the freed slaves began integrating within New Orleans decades after the first arrival of Haitian refugees, the Creoles made it apparent that they saw themselves as more sophisticated and in a different class to the newly freed slaves. The Creoles stuck to their downtown location, whereas the African Americans were forced to live in uptown, with their being two distinctly different black experiences existing in New Orleans for a number of years. However, musically speaking, both came together in a place called Storeyville, better known as the red light district of the city.

When the Spanish took control of New Orleans, two great fires set the city ablaze, leveling almost the entire city. In response to the devastating events, the Spanish authorities rebuilt the city mimicking another one of their colonies, Havana. This is actually where you get the traditional architecture in what is now known as the French Quarter, ironically having been actually constructed and designed by the Spanish. However, more importantly to the story of jazz, the authorities redesigned the entire economy of New Orleans to also work in a similar manner to Havana, specifically for a large amount of revenue to come in through sex work. In order for brothels to stay competitive in Storeyville, they would hire local musicians to perform both to people on the street as well as when clients were being tended to. The owners didn’t care whether a black musician was African American or a Creole, they only cared whether they attracted more customers. As such, the musical abilities of both black classes started to intermingle and rub off on one another.

Around this time a new popular style of music was emerging called ragtime. With a somewhat disputed origin, the style was purely performed on the piano and featured a considerable amount of syncopation in comparison to prior piano music. As a piano only style, ragtime naturally came out of the world of popular printed sheet music of the century, having strong links to classical pieces as well as coon songs. Although the exact year it entered popular culture is unknown, it was likely in rotation in the later parts of the 19th century. At first ragtime was simply a name used to market a large handful of solo piano styles that were loosely more syncopated than earlier works, however by the early 20th century it developed into a specific style with fixed characteristics. The most common form was AABBACCDD, likely coming from the march tradition and with each letter being 16 bars. Typically the CC section was called the “trio,” further reinforcing the connection with marches as this was also a typical name used in that tradition, and would modulate to the IV of the key. A lot of the syncopation was generated from the inclusion of the “Spanish Tinge,” as well as dividing bars of consistent eight notes into hemiolas and variations of 3, 3, 2 accents.

Maple Leaf Rag

Scott Joplin

And with that we have arrived at the start of jazz. Right now you probably are wondering why we just spent so long unpacking the blues, American popular music, and creolization. Well that’s because every musical element we have covered plays a major role in defining what Early Jazz sounded like, so much so that you could potentially argue that some of the precursor styles we have covered should be considered part of Early Jazz too. However, that is an argument for another time, as right now we have finally arrived at the crucial point of this resource, the moment where everything comes together to demonstrate how to recreate the sound of Early Jazz in our own music. So let’s dive in!

Gumbo

With all of the musical influences in place and a location such as New Orleans to bring them together, Early Jazz likely started to form sometime around the late 19th century. Unfortunately the first recordings we have of the style are from 1917 with the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, which are wonderful to listen to but don’t necessarily reflect the true nature of the musicians in New Orleans due to the band consisting of an all white cast of musicians. Instead it would be a number of years later where the more prominent figures of the scene would start to be recorded, often well past their prime and only showing a glimpse of what the true nature of Early Jazz likely sounded like. As a result, we will never know the true colors of those first few decades but nonetheless we can still piece together the characteristics from the wonderful recordings we do have.

As we have established, there were a lot of musical influences that led into the creation of Early Jazz, each of which coming from different backgrounds. While we have already explored each of them individually in their own contexts, now the fun really begins as we get to see how they intermingle with one another. In order to recreate the sound of Early Jazz authentically, I’ve divided the characteristics into a number of different categories so that you can see exactly how they interacted with each other.

It definitely looks like a wide spread of characteristics when they are all laid out next to each other, but we’re not done yet. This resource isn’t purely about understanding where certain characteristics came from, it’s also about being able to actively use that knowledge in our own writing. To be able to do that, we must know what each of these characteristics looks like musically in the context of Early Jazz. For example, just because the piano part is influenced by ragtime, what does that actually mean when we write our own Early Jazz piano part? Below you’ll find an exhaustive list of musical examples, unpacking the most common approaches for each of the characteristics listed above.

Instrumental Roles

Depending on the year, the instrumentation for an Early Jazz ensemble could vary quite drastically. Initially the most common format was to have three horns up front, which included the cornet, clarinet, and trombone, as well as some kind of rhythm section featuring the banjo, tuba, and some kind of rhythmic accompaniment such as the washboard or an early form of the drum set. Over time changes were made, namely the inclusion of the piano, the transition from the banjo to the guitar, and the transition from the tuba to upright bass. Each of these new instruments brought a different timbre to the ensemble, impacting the overall feel and pushing the sound of Early Jazz into something completely different. However, we’ll get to that in a different resource. Fortunately for us, even though the instruments may have changed, their roles stayed the same which makes emulating the sound of Early Jazz a lot simpler.

Before we get started it is worth noting that what we are about to discuss is a generalized view of Early Jazz instrumental roles. Over the vast amount of recordings there exists a considerable amount of variation and it would be impossible to cover every nuance. For example, sometimes the melody is shared around the ensemble which can sometimes mean certain roles are exempt or reassigned to a different instrument. So take the information we are about to cover as a foundation for your understanding and then as you listen to more music from this time, try to pick up the differences each artist brings to the table.

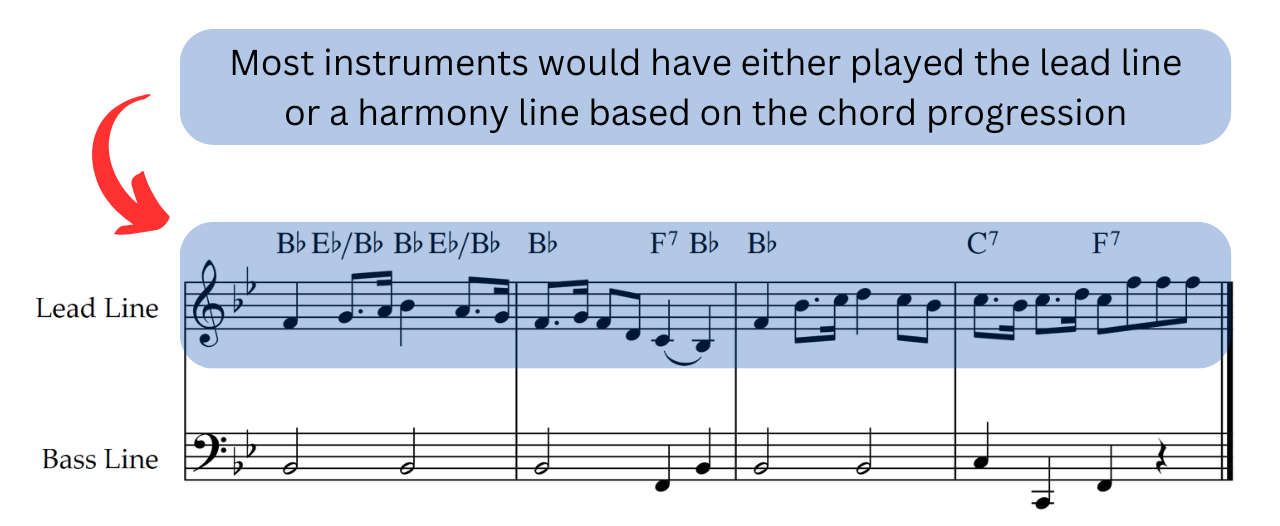

Coming from the brass band/wind band tradition we get many of the instruments in an Early Jazz ensemble, with the main exception being the banjo and piano. As such, many of the original roles of these instruments were translated to Early Jazz via the Second Line interpretation of the later 19th century. What that means musically is that the cornet and clarinet both take on the melody. However, the clarinet is typically placed an octave higher than the cornet and has the option to create an obligato, a line built around connecting guide tone resolutions through either step wise motion or arpeggiation. The trombone on the other hand follows in the tradition established by David Wallace Reeves and plays a simple counterline built around fundamental chord tones.

Black Bottom Stomp

Jelly Roll Morton

Turning to the rhythm section, the bass line is assigned to the tuba and is typically played in a two feel with root notes or 5ths landing on the downbeats. Very much in the same vein of how the tuba operated in brass band/wind band music. For the two remaining chordal instruments, the banjo took on the same role that it originally played in early African American music and primarily played chords on all beats. When the piano was introduced it played a hybrid of both the tuba and banjo parts, with the left hand playing in a ragtime style with down beats doubling the bass part and beats 2 and 4 playing chords. The right hand was then free to do as it wished, whether that be doubling the banjo part with chords, or taking on more adventurous ground and playing the melody or solo interjections.

Finally, that leaves us with the drums. Unfortunately due to the limited recording technology of the early 20th century, most drums were omitted from recording sessions as they couldn’t be captured accurately. In their place, sometimes the drummer would play an assortment of percussion such as woodblocks and cowbells, as well as utilizing brushes instead of sticks, however this option usually was buried aurally and is quite hard to distinguish even today. As a result, these days we have to imagine what the drums may have been playing based on the influences we know about. It is likely that if the drums were present, they would have accompanied with some kind of march-like pattern, primarily playing time on the snare drum and some kind of basic down beat orientated pattern on the bass drum. The favored cymbal of the time was some sort of small crash cymbal, mainly used with a choking technique to help accent band figures or provide fills between sections.

Black Bottom Stomp

Jelly Roll Morton

Style & Form

Although there were many styles which influenced the beginnings of jazz, these days Early Jazz is generally summarized by a singular sound, one which is defined by a brisk tempo and features collective improvisation. The main reason for this is due to the popularity of that approach in the recordings of the 1920s. Audiences fell in love with the sound of Early Jazz artists, starting with the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, and as a result record companies pushed that approach more than others. Within that sound there were a few particular style names which seemed to be used more often than others, some lingering from prior traditions such as the blues, as well as new names such as stomp. All of which helped represent the breadth of styles available to Early Jazz musicians.

Unfortunately, defining the particular style of a piece can be difficult as many sound quite similar to one another. Sometimes it is the particular form that causes a piece to be titled a certain way, and in other cases it may be the tempo or harmony. As such, there is no “right” way to define the styles of Early Jazz and depending on your background you may refer to them differently to me, the main point is to know that they exist and how to differentiate them from one another. The most common categories I’ve come across are: Blues, Rag, Dirge, and Stomp.

Blues

Typically defined by the 12 bar blues form, it prominently featured a dominant IV chord with later recordings also highlighted the dominant I chord. Generally featured a range of tempos from slow to fast.

Rag

Typically defined by an AABBACCDD ragtime form, however rag was a term commonly used to mean syncopated, so there are many examples of rags which are not derivative of the ragtime form. Generally featured a moderate to bright tempo

Dirge

Typically defined by a slow tempo and is usually used alongside African American hymns and spirituals

Stomp

Could feature a multitude of forms other than the blues and generally featured a moderate to fast tempo

Fortunately, unlike the various styles which made up Early Jazz, when it comes to form there is a bit more consistency with naming conventions. There were many forms for musicians to draw upon in the early 20th century and in general it was a highly creative time across all fields of American music. Unlike prior centuries which abided by strict composition rules, the form of a song didn’t have to be set to a particular formula and could freely be stretched, reduced, or ignored altogether. As a result, there was an abundance of different forms that were created during the period across all styles of music. While it would be almost impossible to represent every possible creation in this resource, I’ve decided to instead focus on the most popular forms used by Early Jazz musicians as well as highlight the origin of each form.

Blues

8, 12, and 16 bar blues

Ragtime

AABBACCDD

Classical

Binary AABB

Ternary ABA

Rondo ABACA

Hymn

Verse + Refrain

March

AABBCDCDC

Popular Song

AABA

Verse + Chorus

Harmony & Harmonization

For the most part, harmony in Early Jazz was built around two pillars: the blues and 18th century diatonicism. While in some popular songs of the day there were examples of non-diatonic techniques, these were mainly explored outside of Early Jazz and started to be incorporated into jazz through later composers such as Duke Ellington and Fletcher Henderson. As such, the basis of Early Jazz harmony follows the typical classical approach, making use of all of the common harmonic devices available. These include techniques such as secondary dominants and secondary key centers, modulation, and a variety of cadences. The only exception to this was the incorporation of blues harmony, specifically the dominant I and IV chords. However, when utilized, these two chords were often integrated alongside conventional Western harmony practices. For the most part, chord progressions were simple compared to later genres of jazz, with more emphasis being placed on the contrapuntal nature of each instrument as well as the relation between chords. Very few extensions or alterations were utilized, with the music instead relying primarily on triads and 7th chords. If a color tone was used, it was primarily thought of horizontally and by happenstance it lined up as an extension or alteration of a given chord symbol. Finally, when it came to passing chords, almost always diatonic options were used, however diminished passing chords were also a viable option.

When the horns were written in voicings, the preferred technique was to use 2 or 3-part harmony which reinforced the fundamental harmony of the accompanying progression. Due to the difference in registers between the three frontline horns, it was common for there to be an octave or more between each part, with the most utilized voicing being some kind of triad or 3rd/6th with octave displacements.

Black Bottom Stomp

Jelly Roll Morton

Rhythm & Articulation

One of the large shifts that started with the ragtime craze in the late 19th century and continued on into Early Jazz was the change in rhythmic emphasis. Prior to ragtime, most American music followed the European conventions and had a heavy downbeat, however with ragtime, popular music began having more syncopation and provided more equality among each eighth note/quaver subdivision. This approach changed the flow of pieces and gave a forward momentum to Early Jazz which helped it stand out among the other music of the day.

Early Jazz also began to innovate in the area of articulation. During the end of the 19th century the common convention was to articulate every note either short or long in a pronounced manner. This resulted in lines feeling almost over articulated compared to today’s standards. While it is likely the first jazz musicians would have stuck to these conventions, by the time the first Early Jazz recordings were made the approach had shifted drastically to a more legato style of playing. Many scholars credit Louis Armstrong as the main force behind this shift in Early Jazz, as well as link him with giving forward momentum to phrases as mentioned in the prior paragraph. However, even though he was a major influence on the trajectory of Jazz in the 1920s, it is a bold claim to link such a large contribution to a single person when there were likely others who also helped contribute to the shift in articulations and rhythmic emphasis

Other Notable Characteristics

Although Early Jazz did incorporate various components of 19th century American music, it also innovated and brought even more elements to the fray, one of which being the swing feel. To begin with, the swing feel was not one unified approach like it is today. Instead, Early Jazz had numerous different interpretations, however we only know this because the recordings of the 1920s all demonstrate different approaches to swing. What that means is that in the years prior to recording, the musicians were likely still experimenting, with some playing more straight and others more swung. Artists such as Jelly Roll Morton were known to have a relaxed triplet feel paired with a legato approach to the piano, often giving the impression of swing when in fact the music was quite straight compared to today’s standards. Unfortunately, we will never know exactly when swing started to enter Early Jazz and how much lilt was given at the beginning, but by the 1920s, when the majority of Early Jazz recordings were created, we do know that the concept of swing had already started to be developed by various musicians.

Improvisation was also quite different to the modern day approach. Almost always improvisation meant embellishing the melody, or making the melody one’s own, similar to the second line tradition. What that looked like practically was moving the melody around and adding syncopation in response to the other instruments. Typically the main improvisers were the three horns up front, each with a defined register in which they sat. Not every piece stayed to the formula with some songs featuring melody on the trombone, such as those by the Kid Ory band, while others like Sidney Bechet featured the clarinet (or soprano sax) on the melody. If chromaticism was ever used, it came in the form of chromatic approach tones and lower/upper neighbor tones. Like the swing feel, the recordings of the 1920s often showcase a more complex form of improvisation, representing a departure from embellishing the melody and instead opting for the creation of completely new improvised melodic lines. However, we will touch on that more in a later resource when we cover the Jazz Age in more detail.

Another notable characteristic of Early Jazz was the use of breaks, typically two bars long, which would feature an instrument playing an unaccompanied solo. Based on the wonderful interviews with Jelly Roll Morton that have survived to this day, these breaks were seen as one of the pivotal points in a tune and were a quasi test to see if a certain player or band could really cut it. These days they would be the equivalent of a solo break, however in Early Jazz they were far more common and could be as frequent as every 8 bars in some cases.

It was also quite common for rhythm sections to utilize stop time when accompanying a soloist. Instead of playing a consistent time feel, they would shift to small groupings of hits, giving more space to the soloist and allowing them to show off more of their virtuosic abilities. While stop time was generally played by the rhythm section, they could also be joined by the horns who would further reinforce the hits, either in unison or harmony.

Black Bottom Stomp

Jelly Roll Morton

One final innovation that is worth mentioning is the work of Joe “King” Oliver, who helped introduce various brass mutes into Early Jazz. At the time, the mutes available for cornets were quite limited, with the most common option being some form of straight mute. Oliver decided to experiment profusely with different objects such as bottles, cups, and rubber plungers to see how they impacted the sound of his horn. As a result, he created a legacy of muted brass that has carried on for generations and still impacts brass players today. Notably, Oliver was one of, if not the first, person to utilize a household plunger to create a wah-wah effect in jazz, as well as heavily contributed to items such as buckets and hats being used as mutes too. Eventually this led to the creation of bucket mutes and derby hat mutes for brass instruments.

Notable Artists

Now that we’ve unpacked pretty much everything when it comes to Early Jazz, there is one last topic to mention, the incredible artists! As with any sort of music, every musician which recorded Early Jazz had a different approach, some were quite similar to each other while others were drastically different. Many artists also refined and changed their approach to performing over their lifetime and were highly versatile. It would be a gargantuan effort to try and analyze and summarize every single prominent Early Jazz artist and realistically that falls outside of the scope of this resource. Instead I leave that job up to you. Take the characteristics we’ve now unpacked and see how they apply to the musicians I’ve listed below. Sometimes you may find exceptions, perhaps a different instrumentation or different sort of harmony, all of which are completely valid and will help deepen your understanding of the musical characteristics of Early Jazz. If you find anything that stands out, let me know, and maybe it will find its way onto this page in the future.

Sidney Bechet

Louis Armstrong

Joe “King” Oliver and his Creole Jazz Band

Freddie Keppard

Jelly Roll Morton

Jonny Dodds

Jimmy Noone

Original Dixieland Jazz Band

Earl Fuller

Bunk Johnson

Buddy Petit

Kid Ory

Sam Morgan Jazz Band

Clarence Williams’ Blue Five

Bix Beiderbecke

The Takeaway

And with that, we have covered all of the major characteristics of Early Jazz. While no single document can capture every single nuance that exists for an entire era of jazz, I have tried to be as thorough as possible with this resource and explore the various links that helped create Early Jazz. However, as you are probably aware, the story doesn’t stop at Early Jazz, and at the same time the first recordings of Early Jazz were being made, a new generation of musicians were putting their spin on the music in cities around the United States. But I’ll save that story for the next resource where I unpack the Jazz Age.