What Happens When Jazz Breaks

Free From Tonality & Diatonicism

For many, the music of the 1960s represents some of the most exciting jazz recordings of all time. Whether it be the various albums by artists like Miles Davis or John Coltrane, the explosion of fantastic Blue Note recordings, or the wide variety of different styles, there’s no shortage of great music. The period also features some of the most interesting harmonic developments in jazz history, where the music starts to abandon functionality and explore completely new ideas. However, understanding how the music works can be quite difficult if you are unaware of how certain musicians were thinking at the time. Well at least that was the case with me.

As I’ve mentioned in other resources, like most musicians, when I started out I cared far more about being able to play music rather than understand the ins and outs of theory. It just so happens though that some of the music I first was drawn to as a young bassist fell into harmonically complex ground such as the compositions of Herbie Hancock and Jaco Pastorius. Having almost no analytical ability, the harmonic nuances of their recordings were lost on me as a teenager, with my main priority being to try and capture the fantastic bass lines. However, as I slowly was introduced to the inner workings of diatonic music theory thanks to pursuing an undergraduate degree in jazz studies, the more I looked at charts like Speak Like A Child the more I was confused.

When I was plunged into the world of music theory as a first year student, the main curriculum covered figured bass and functional counterpoint, two areas that only go so far when trying to analyze modern jazz. I was consistently perplexed by the chord progressions of Wayne Shorter and Chick Corea, never seeing how anything related to the theoretical techniques I was being taught. At times the chords seemed to operate functionally but at other times it felt like they defied any sort of theoretical logic. This feeling lasted for a surprisingly long amount of time until I finally was admitted into the advanced arranging classes. Thanks to professor Rich DeRosa, the harmonic developments of the 60s started to become justified and it became obvious that there were systems in place behind many of the chord progressions from the period.

What I started to realize was that postbop harmony moved beyond the established tonal conventions of prior jazz styles. While the musicians never seemed to stray too far from where they had come from, at the same time they pushed jazz into a new harmonic territory that was completely unique and not linked to any of the major developments that had occurred in Western classical music. Most of the techniques stemmed from a singular idea to avoid traditional resolutions, instead prioritizing a sense of harmonic ambiguity. There were many ways that this was achieved, from focusing on intervallic relationships, specific chord sounds, as well as placing traditional resolutions in unconventional places. Now not all jazz musicians of the 60s made use of these harmonic devices, with some preferring to focus on new styles such as bossa nova and soul jazz, but many of the popular hardbop artists did and thanks to people like Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Joe Zawinul, Chick Corea, and a whole slew of others, jazz harmony was forever changed.

I’ve tried my best in this resource to capture the common techniques used by these artists, however there very well could be examples that have escaped my attention due to there simply being so many new harmonic developments found in the 1960s. As each technique generally takes a different approach to achieve harmonic ambiguity, what you’ll find is that this particular entry is in some ways more comparable to the technical resources I’ve written such as those on voicings or extensions, more so than the others which focus on particular styles and eras. However, when necessary I’ve tried to link in a level of context which is typically absent from my technical resources. Like always, my hope with this particular resource is that you’ll be better able to capture the sound of the style within your own writing, or at the very least be able to understand what is going on in the music a little bit more than before. To get us started, let’s first have a look at what postbop actually is because that will help situate the sound within the context of jazz history.

What Is Postbop?

The name postbop can be quite confusing because it is often used to refer to any style which came after bebop. To some degree that could encapsulate a wide variety of different styles with many having drastically contrasting musical characteristics, making it almost impossible to narrow down for a single resource such as this. However, as a style marker, postbop is often used primarily as a way to describe the jazz styles which emerged in the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s, specifically those which started to move away from the characteristic sounds of bebop and hardbop. With this framework in mind, the major styles which are often included under the term are modal jazz, free jazz, and the music of those such as Herbie Hancock or Wayne Shorter which mark a notable progression from the hardbop sounds of the 50s. For the sake of this resource, I will specifically be using postbop to refer to this latter category as I’ve already explored free jazz and modal jazz in other resources.

What is unique about postbop compared to earlier styles is that it is one of the first major instances in jazz history where harmony strayed considerably from common Western classical conventions. Thanks to the development of modal jazz, there was a shift away from both functionality and tonality which were then amplified further through the creation of a number of new techniques. While many artists did draw from a similar pool of ideas, there was a fracturing which took place where jazz felt even more individualistic than prior decades. As a result, many of the harmonic techniques developed often became part of the signature sound of certain artists more so than universally utilized approaches. For example, comparing the music of Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey is rather straightforward as they both played music which highlighted Swing Era characteristics, however comparing Chick Corea and Wayne Shorter is more complex as each had a far more individualistic sound even though they came from the same period of jazz history. To try and provide some sort of throughline between all of the unique postbop approaches in the 60s, this resource primarily focuses on the core concept of harmonic ambiguity and how different artists were able to create the effect in their music. Outside of harmony, many of the other characteristics present are directly related to prior styles such as hardbop, so you may find it helpful to read my other resource on the topic before continuing on. With that said, let’s jump in.

A New Direction

Thanks to the release of a number of albums at the end of the 1950s, notably Kind of Blue, Giant Steps, and The Shape Of Jazz To Come, jazz was primed to move in significantly new directions in the coming years. The innovations of bebop had finally been worn out and the next generation of musicians were ready to push the music further. To do so though, meant rethinking the very core of jazz and shifting away from the established conventions that had been with the artform since its inception back in the late 19th century. One such approach was to escape functional harmony by exploring the sound of a single chord with the creation of modal jazz. Another was to break completely from tonality and meter, and allow individuals the freedom to express themselves however they saw fit through the development of free jazz. However, not all musicians ventured down these two paths, and if they did, they didn’t always stick to just one approach. Instead, postbop developed as a third option which looked at other ways to break free from the traditional harmonic mold of jazz.

Interestingly, while postbop moved in a different direction to both modal and free jazz, perhaps one which was more closely related to the status quo at the time, it was influenced by the other two styles in various ways. For example, thanks to modal jazz there was a new way to approach improvisation, resulting in a non-diatonic technique which allowed for certain chords and scales to be utilized without the need for any sort of functional resolutions. The style also drew attention to three prominent modes which became increasingly popular in the years after the release of Kind of Blue, including the Maj13#11 which implied a lydian sound, Min13 which implied a dorian sound, and Dom7sus4 which implied a mixolydian sound. Unlike in modal jazz where each of these chords could be highlighted for extended periods of time to allow improvisers to explore the sound of the given mode, in postbop they started to be implemented in more conventional progressions, often being allocated in a similar manner to functional chords while still maintaining a non-functional sound. A quick look at Wayne Shorter’s Infant Eyes showcases an abundance of these chord sounds alongside many other techniques which we will get to shortly.

Infant Eyes

Wayne Shorter

On the other hand, free jazz also seeped into postbop to a degree, specifically in the recordings of Miles Davis’ second classic quintet. Although Miles openly critiqued the direction artists like Ornette Coleman were taking, he and the musicians in his ensembles did incorporate elements of their approach in the 60s. Notably, they drew from the first wave of free jazz where it was common for both the drums and bass to play an underlying time feel drawn from no particular time or key signature while a soloist improvised above. Miles referred to this approach by the self explanatory title “time no changes,” a technique which he incorporated to a great degree and can be heard on tracks such as Pinocchio from the Nefertiti album. The main difference between free jazz and Miles’ approach though, was that Miles utilized the technique more so as a texture within the solo section of a piece rather than as the sound of an entire composition.

Alongside the development of modal and free jazz, there was one other critical influence which helped pave the way for postbop that must also be mentioned. Now seen as one of the quintessential jazz albums of all time, Giant Steps by John Coltrane featured a new way of navigating harmony. Up until that point, most jazz repertoire drew from the harmonic language of the Great American Songbook or the blues, two mediums which generally worked within the restrictions of a single key. If the progressions were to move outside of the key, almost always the harmony was related back to the home key through secondary resolutions, giving the illusion of drastic modulations while still being drawn from the original tonality. However, Coltrane pursued a different route, looking for connections through intervallic relationships, specifically the major 3rd (M3). In the actual composition Giant Steps, Coltrane wrote the entire progression around this idea with every resolution cycling between a Bmaj7, Gmaj7, or Ebmaj7 chord. The result was a sound which highlighted the M3 relationship more so than a given tonality and helped establish a unique path away from common diatonic conventions. Now instead of focusing on establishing a given key, artists could instead write progressions built around intervallic relationships and cycles.

Giant Steps

John Coltrane

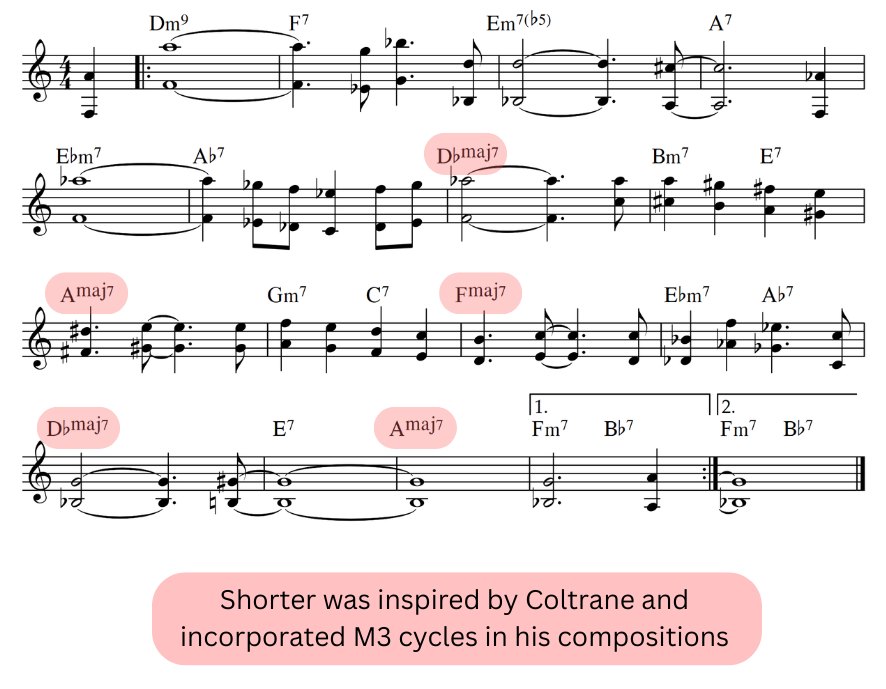

Not long after the release of Giant Steps, other musicians embraced the idea of M3 and m3 cycles. Some were more obvious than others and followed a similar path to what Coltrane had gone down, whereas others used the general idea more broadly within the resolution points of their pieces. In the case of Wayne Shorter’s El Toro, he used the latter 8 bars of the piece to emulate Coltrane’s progression while also combining it with the Maj13#11 sound.

El Toro

Wayne Shorter

Although these three influences sounded completely different, each achieved the goal of pushing jazz into a new realm of harmonic possibilities, one which was no longer tied to the tonal resolutions of yesteryear. Collectively they rewrote what jazz harmony represented and provided a new foundation for musicians in the 60s to build off. The stage was set, now all that was needed was for a new wave of ideas to be applied.

Harmonic Ambiguity

In a similar manner to how Western classical composers grew tired of the standard tonal conventions of romantic music in the 1800s, jazz musicians came to a crossroads at the end of the 1950s. Having thoroughly explored the limits of tonality and functionality, jazz was in a position where in order for it to progress it had to explore new territory. For some musicians that meant looking for inspiration outside of jazz with styles like bossa nova, while others looked to challenge the core infrastructure jazz itself was built on. For those in the second category, everything was up for grabs. As we’ve just seen, this resulted in a number of major departures from diatonicism, particularly showcased by a few key releases in 1959. However, through the development of postbop in the 1960s, even more ground was covered.

Across all of the techniques used, one key idea linked them all together, the idea of breaking long held conventions. Whether that be highlighting a given tonality through diatonic chords, common forms such as AABA, or phrase lengths following a 2, 4, or 8 bar structure, everything was up for grabs and could be altered. One outcome of challenging these conventions was creating a music which no longer had a formulaic approach, or at least did not give the impression that it followed a standard set of rules. Interestingly, while free jazz did depart heavily from all major conventions, postbop was rather timid in comparison and usually only pushed the boundary in one direction while maintaining many of the other elements of hardbop. For example, if a composition drew more heavily from non functional harmony, it would often have standard phrase structures and a common form. The result was an ambiguous sound more so than straight defiance, where at times the music felt as if it belonged to prior styles while also having one foot in a new direction.

In order for the music to stop prioritizing traditional cadence points, one solution that postbop musicians came up with was to highlight dom7sus sounds. Due to the removal of the 3rd, there was less pull to a resolution point, allowing for the harmony to stay stagnant to a degree. Additionally, there was a general tendency to highlight the ii chord in a ii-V progression more so than the V, eventually leading to the ii chord often being used in place of V chords. For both techniques you don’t have to look far to find an example as they both dominate the sound of postbop. Two fantastic examples though are Mahjong by Wayne Shorter and Speak Like A Child by Herbie Hancock. Right out of the gate, Shorter highlights a ii-I resolution throughout the A section of Mahjong, while in Speak Like A Child many of the V chords take on a sus quality. Both achieve the same effect of removing the typical resolution that one might expect coming from prior jazz styles.

Mahjong

Wayne Shorter

Speak Like A Child

Herbie Hancock

However, changing the feel of a V chord was only the start and through the development of three other approaches, tonality and diatonicism was pushed even further. Up first was the idea of using extensions and substitution to relocate traditional guide tone resolutions. For example, instead of going G7 to Cmaj with the inner tones of F resolving to the E and the B resolving to the C, the Cmaj chord may be changed to a completely different option that still maintains the E and C tones somewhere in the chord. One of the most straightforward substitutions was to use a mediant relationship with the target chord, exchanging the original chord with one located a third above or below. In this case, the Cmaj could be swapped with some kind of A, Ab, E, or Eb based chord. A great example of this is in Windows by Chick Corea between the Ab7 and Emaj7. As Ab7 traditionally sets up a Db/C# chord, in this case the Emaj7 can be seen as a substitution for C#min, with all of the original guide tones resolutions represented albeit in a different format. When listening to the track, it feels as if the piece has shifted to an entirely new place but upon closer inspection we can see that the chord change is actually far more in line with traditional harmony than to be expected.

Windows

Chick Corea

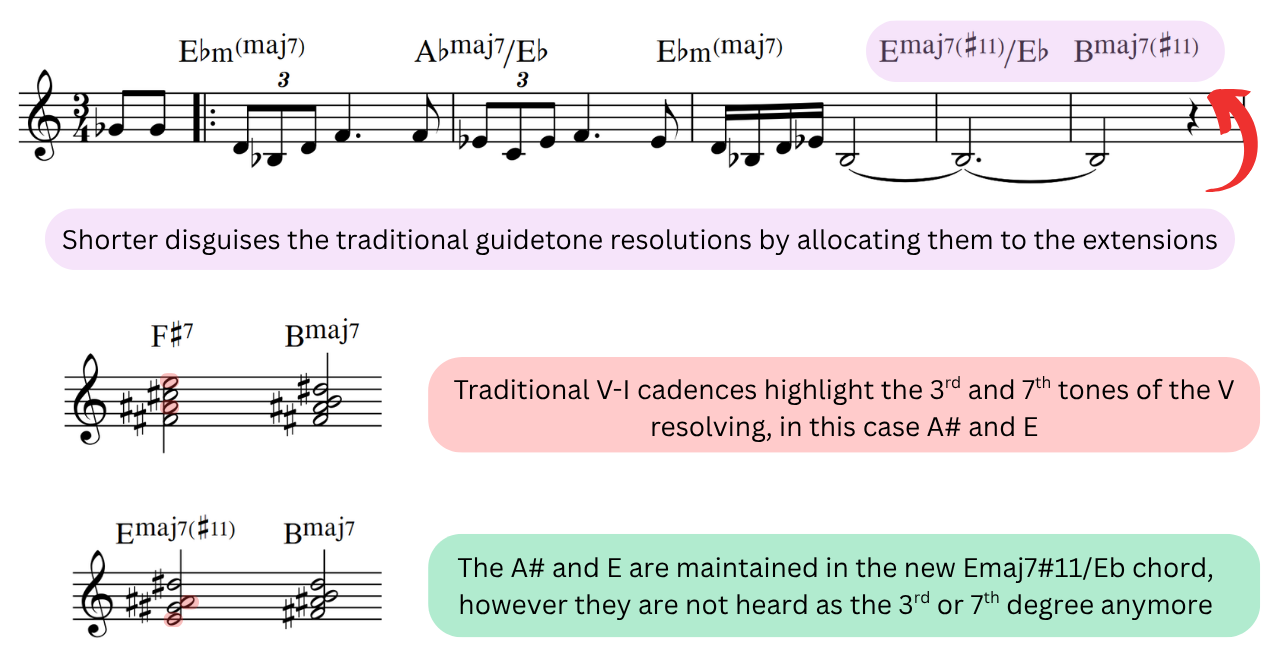

Alternatively, instead of substituting the target chord, it was also common to substitute the leading chord. Often this would be done in a much more disguised fashion, where chord progressions on the surface would look as though they were shifting tonalities with no resolution taking place whatsoever. In reality, what was going on was that the prominent guide tones would be maintained somewhere in the extensions. Penelope by Wayne Shorter offers one such example between bars 4 and 5, where the chords go between an Emaj7#11/Eb to a Bmaj7#11. In the context of the piece, the first chord is part of an ongoing pedal point which makes the transition come completely by surprise. However, below the surface what we can see is that the Emaj7#11 was used specifically to bridge the two sections together. Typically when resolving into a new chord, the normal convention would be to set up some sort of V-I resolution where the 3rd and 7th degrees of the chord would outline the key resolution pathways. In this case the two prominent notes would be A# and E. Taking a closer look at the Emaj7#11/Eb chord, what we can see is that these two notes have been reassigned to the root and #11th but are still featured, meaning that the chord will still resolve to the following Bmaj7 chord even though it doesn’t seem as conventional.

Penelope

Wayne Shorter

This particular idea of relocating guide tones taps into the second prominent harmonic approach used by postbop musicians. Coming out of bebop and hardbop where it was the norm for as many color tones to be utilized, some musicians instead started to specify exactly what chord tones they wanted to be played. What this looked like in practice was using chord symbols that often included some kind of triad over an unrelated bass note. Instead of C13#11, a number of other chords such as D/C, Bb+/E, Am/F# and so on could be used. As a result, chord progressions still maintained a level of functionality but now only identified the exact sounds that the composer wanted to highlight. In the final section of Chick Corea’s Inner Space, an E/F is used, the only chord of this type in the whole progression. While it is entirely possible that Corea liked this particular sound, another possibility is that Corea was tapping into this particular idea of reducing a chord down to only a few notes. Looking at the proceeding chord, an Ebmin7, it is likely that the E/F was actually drawn from some kind of Bb7. When looking at the fundamental chord tones, this may seem farfetched, but if you were to think of it as a Bb7b9#11, suddenly all of the notes of E/F are now justified.

Inner Space

Chick Corea

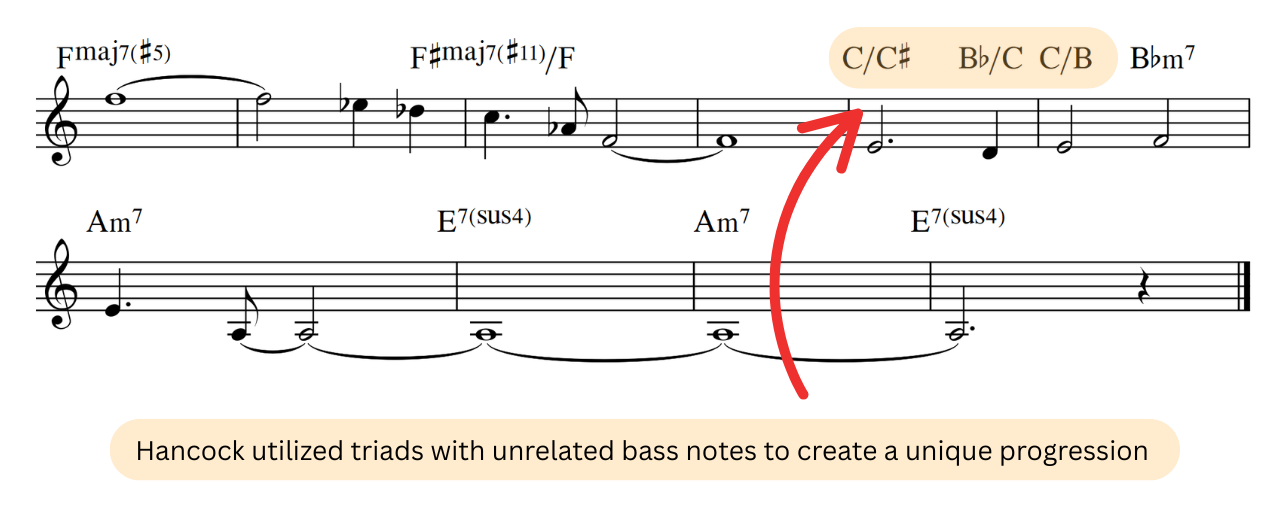

The primary name for these types of chord symbols are slash chords, but in the past I’ve also come across the term abstract harmony to describe this particular sound. While they can be generated by simplifying existing chord symbols, it was also common for the chords to be created by placing an unrelated bass note against a given triad. For example, if you had a Cmaj triad you could place any note other than the three in Cmaj as the bass note to achieve a slash chord sound. By far the most common were the five tones that did not belong to the scale implied by the triad. So in the case of Cmaj, the notes would be Db, Eb, F#, Ab, and Bb. These particular bass notes, as well as the 7th degree of the scale (in this case B), provided some of the more interesting combinations, and helped distance the overall sound from a conventional chord symbol. Hancock’s Speak Like A Child is a great example of this technique being utilized in the final few bars of the melody. He particularly uses Cmaj/C#, Bbmaj/C, and Cmaj/B to create a pretty unique progression that is hard to link to any conventional techniques.

Speak Like A Child

Herbie Hancock

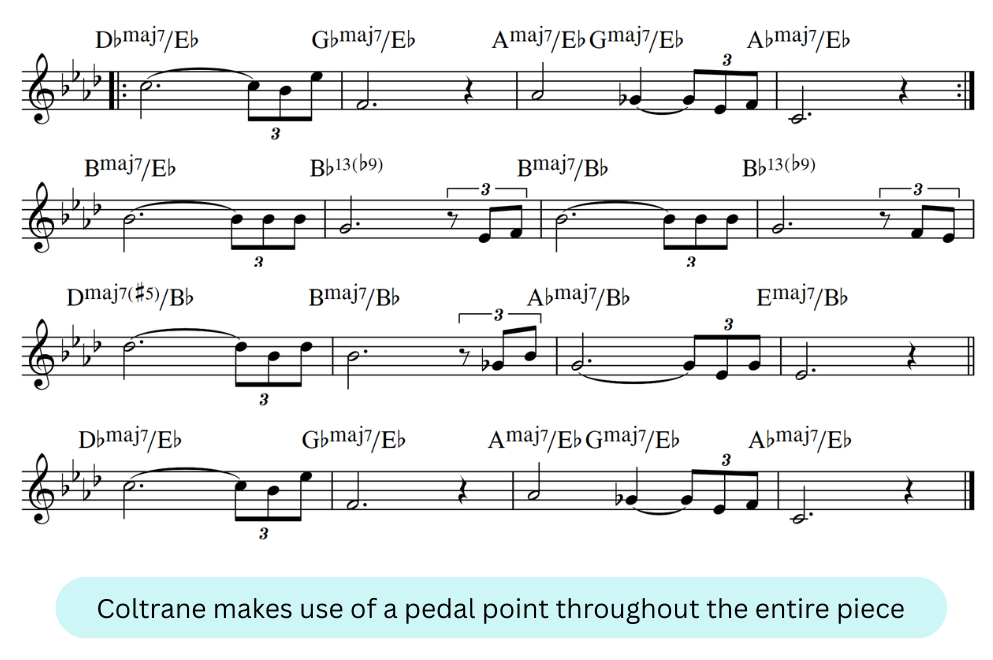

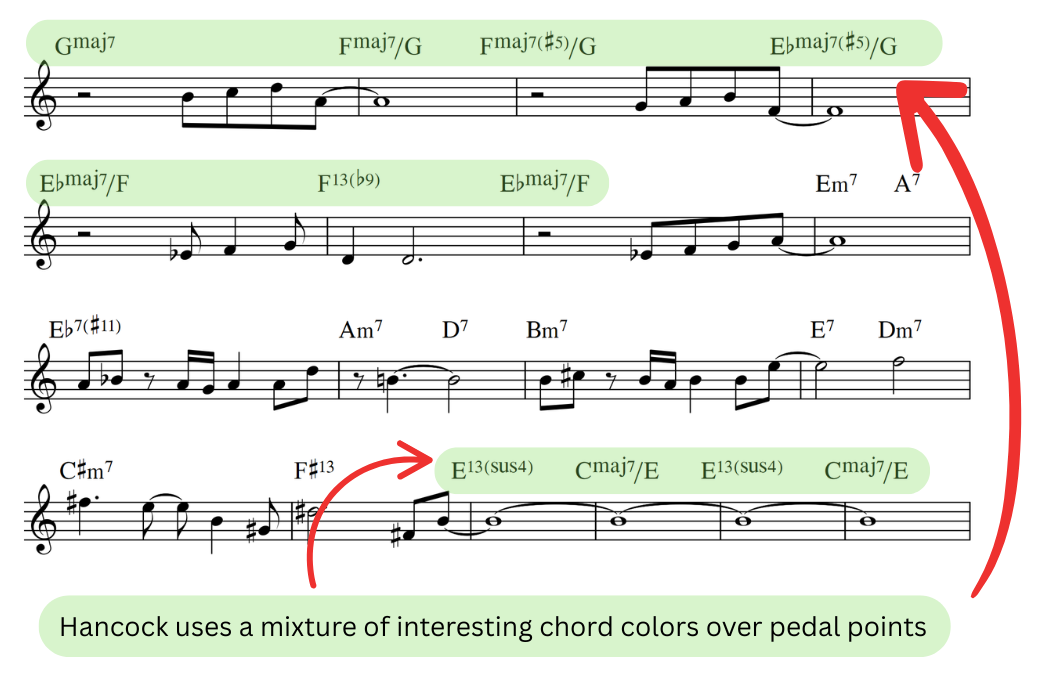

The exact origin of abstract harmony is somewhat hard to locate as there are a number of different possible sources. One of my favorites is the classic Hancock story where he thought Miles had told him to stop playing the “butter notes.” Not knowing what he meant, Hancock figured Miles was talking about the 3rd and 7th of a chord so started to omit them from his voicings. However, the presence of the sound had already been established elsewhere, particularly in the music of Coltrane. A quick look at Naima reveals similar types of harmony, with the bass note being selected through the use of a pedal tone. This particular application was quite popular among postbop musicians, with pedal tones dominating many of the most popular compositions. In Hancock’s Dolphin Dance, a pedal is used at two prominent points in the progression, often alternating between slash chords and more conventional chord symbols. It is also important to note that some chords in this format are actually somewhat less interesting than the chord symbol may suggest. For example, Ebmaj7/F and Cm7/F both provide an F7sus sound, with the chord symbol specifying exactly which notes should be played. The trick is being able to identify which symbols are operating as a slash chord or as a more traditional chord option.

Naima

John Coltrane

Dolphin Dance

Herbie Hancock

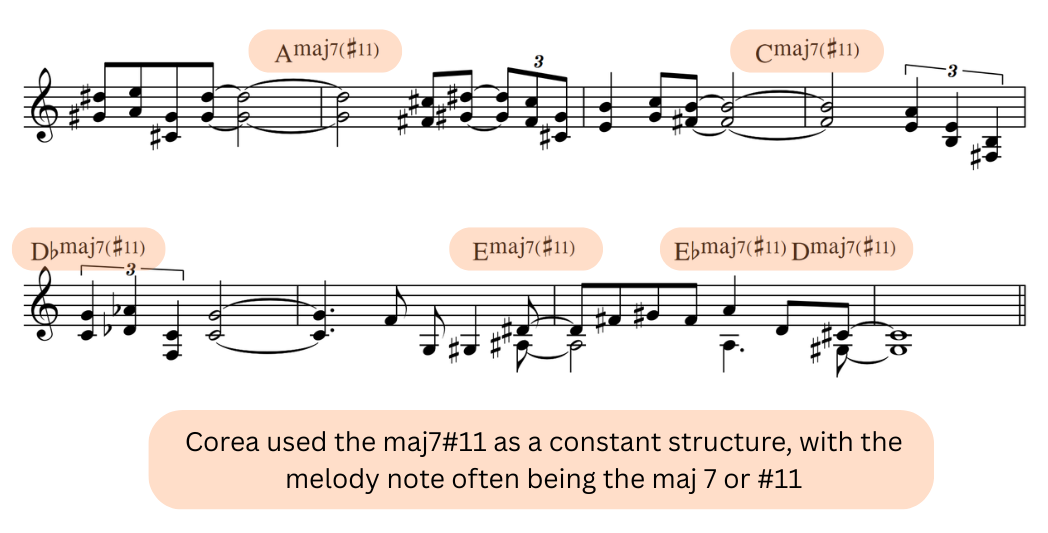

That leaves us with one more prominent harmonic approach to cover, and fortunately for us, when compared to the previous two techniques this one is considerably simpler to understand. Usually referred to as constant structures, this particular approach is when you maintain a given chord quality but change which notes it is built on. For example, if we chose Cmaj13#11, we could then take the maj13#11 sound and apply it to whichever root notes we wanted, such as Dmaj13#11, F#maj13#11 and so on. Although this sound became far more prominent in the 60s, there are examples which date back to the 40s such as some of the compositions recorded in the Birth of the Cool sessions, as well as in Bud Powell’s Un Poco Loco. A more modern example of the sound though can be found in Chick Corea’s Inner Space. Commonly, when constant structures are used, the melody note is almost always assigned to an interesting chord tone such as the #11 or 9th etc. In the case of Inner Space, Corea prominently features the #11 and maj7 in the melody while highlighting the maj7#11 sound.

Inner Space

Chick Corea

The combination of common structures, abstract harmony, and utilizing color tones and substitution to hide resolution points resulted in a drastically different harmonic playing field than what had come before. However, the innovations didn’t stop there and extended to other areas outside of harmony. Instead of always drawing from major or minor scales when writing melodies, musicians started to look at other sounds such as the augmented and diminished scales. There was also a resurgence of the pentatonic scale but now placed over far more complex harmony compared to how it once was presented in earlier forms of jazz. Taking a page from the horn voicings of Horace Silver and the piano voicings of McCoy Tyner, there was also an obsession with highlighting perfect 4th and 5th intervals, whether that be in melodic ideas or in horn voicings, resulting in an open and often angular sound. Phrase lengths were extended and shortened, departing from the normal 2 and 4 bar conventions of earlier styles, and compositions broke free from standard forms such as AABA, instead preferring a single section that would often be an irregular number of bars and not built from the typical 8 or 16 bar length. Collectively, all of these elements created a highly ambiguous sound where it was normal for melodies to never feel concluded and for progressions to endlessly resolve into one another.

There is no doubt that postbop presented jazz with some of the most amazing harmonic developments the artform had ever seen. Thanks to the countless innovations by musicians such as Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, and many others, the entire landscape of jazz was rewritten forever, ushering in the modern era that has extended all the way to the present day. While I’ve tried my best to succinctly mention many of the most common approaches found in the style, know that you could sit out on any one of these techniques and write dozens, or even hundreds, of different unique compositions without any one of them feeling bland. The albums from the 1960s and postbop in particular are some of the most well regarded in the whole of jazz history, yet for some reason the techniques used in many of the compositions and improvisations are often pushed aside in favor of earlier styles such as bebop. Hopefully by making it through this resource not only do you have a level of understanding of what is going on in the music but you can also respect just how creative the musicians were to think of these ideas in the first place.

The Takeaway

For the first time in jazz’s history, postbop created an entirely new harmonic vocabulary with many techniques that rivaled the established rules of earlier styles. Through combining various aspects of the old and new, musicians were able to create an elaborate array of compositions which breathed new life into the artform. Interestingly, the styles that came after postbop have not really offered anything groundbreaking in the way of harmony, instead focusing on incorporating elements of non-jazz related styles such as rock and funk into the music. However, that’s a story for another time which you’ll have to explore in a different resource.