The Formula To Writing

Swing Music From The 1930s

If there was one period in history where jazz was the most popular it would definitely be the Swing Era. For the second half of the 1930s, and the better part of the 40s, swing music was everywhere in the Western world and changed the direction of popular music forever. So much so that as a fifteen year old, some of the first music I ever played were the hits of Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller in my high school's big band. Not only did swing have a dramatic effect on the trajectory of jazz, it was also one of my biggest influences and I likely wouldn’t be pursuing a career as a jazz musician today if it weren’t for hits like Little Brown Jug and In The Mood.

I was very fortunate to grow up in a suburb of Melbourne where the local public school was known nationally for its outstanding music program. Having already fallen in love with playing the cornet a few years prior, it was only natural to continue to learn music once I transitioned to high school. Once there, I picked up the upright bass and by 2009 had successfully auditioned for the senior big band. I didn’t really know what I was doing but somehow had passed the audition and found myself in a new environment, nervously anticipating what would come next.

At the time, the Blackburn High senior stage band was quite different from the average school ensemble. Not because it was exceptionally brilliant, but because the band often played corporate functions around Melbourne. I’ll never forget the first rehearsal when the director walked in and said we needed to learn something in the realm of 40 charts for some kind of performance at the parliamentary gardens the next week. I opened the coveted corporate folder which was stuffed with hundreds of loose pages of music and somehow managed to survive the first rehearsal. At first I found everything extremely overwhelming. With no real jazz bass experience, chord symbols looked like hieroglyphics and I solely relied on my bass teacher pencilling in parts so that I could get by. I was purely focused on just holding on but eventually I started to get the hang of it. It was at that moment where my fear was replaced with excitement.

I can remember it almost as if it were yesterday. The band had been booked for a private function at the exclusive Melbourne Cricket Club, a prestigious section of the 100,000 capacity Melbourne Cricket Ground. The first set had been a bit rusty but everything started to click in the second set. Suddenly, I was no longer worried about my specific part anymore and I started to focus on the other instruments in the band. I was able to hear the ensemble as a whole and notice how the swing dancers reacted to how we played. I’m not too sure if the band was having a good night or I had just reached a point of familiarity with the repertoire, but either way it was the first time I can recall where I started to understand the music on a deeper level. Since then, swing music has always held a special place in my heart. However, that was challenged when I eventually left school to study music abroad in the United States.

Having grown up in the early years of the internet, most of my exposure to music came from peers and teachers. Because I had lived in a world where the music of Miller was the primary repertoire for the gigs I got to play, I didn’t really know how other musicians outside of my immediate circle thought about swing. Once I submerged myself into a larger community though, it was obvious that the general thoughts were that swing music was outdated and also seen to some level as white washing the black American music of the time. I was put in a bind, one part of me acknowledged the new information while another part still wanted to enjoy the swing music I had fallen in love with. Fortunately, while in college I was bombarded with new information on a daily basis, enough for me to quickly forget my internal swing music conflict.

A number of years later I decided to revisit swing music and try to get a better idea of the elements I loved, where they had come from, and to try and understand the social situation which led to artists like Miller receiving more recognition than Count Basie or Chick Webb. What I found was an amazing wealth of music, so much more than the popular hits I had played in my teenage years, and maybe even more exciting was the discovery of dozens of arrangers whose names have been lost to time. I also started to realize that there was far more complexity behind those that created the music and that often because of the distance between today and the Swing Era, that it is easy to generalize exactly what took place. While it is true that white artists were paid higher and received much more financial compensation than black musicians, regardless of the color of their skin, bands in both camps were responsible for establishing a unified sound that departed from many of the established traditions found in Early Jazz. It is just far easier to look at the most popular artists as examples, which is why Miller often has such a negative reception with many jazz musicians today.

As you can tell, it’s pretty easy to get political when it comes to the Swing Era. So instead of focusing on which side is right or not, my aim with this resource is to simply look at the music from a neutral perspective so that you can come to your own conclusions. There’s a lot of ground to cover and far too many artists with unique approaches for a single resource. However, I’ve tried my best to capture the essence of the period through a selection of musicians who all contributed to the big band sound in important ways and my hope is that you can come away from this entry having a better understanding of how to recreate the sound in your own writing.

Ushering In The Swing Era

Picking up where we left off with my earlier resource on the Jazz Age, the start of the Swing Era can very much be marked by following the emergence of Benny Goodman as a national star. After already establishing himself as a fine clarinetist in the 1920s, Goodman and his band were given the opportunity at the end of 1934 for a regular feature spot on the Let’s Dance radio program. Quite quickly Goodman realized that he would need more repertoire and through his connection with John Hammond was put in touch with Fletcher Henderson. It just so happens that Henderson was going through significant financial troubles and agreed to come on as an arranger for Goodman as well as agreed to sell him a large percentage of his existing library. Henderson, and various members of his recently disbanded ensemble, also went one step further and helped Goodman’s band understand how to interpret the music in an authentic manner.

Just like that, an all white band which was being broadcast to a predominantly white audience was being advised by black musicians and playing a selection of charts by the same musicians. In a time of heavy segregation across the United States, it is fascinating to know that such a partnership occurred and that it didn’t originate from Henderson being exploited. Of course it is highly unfortunate that Henderson had to go down that route after leading a successful ensemble for over a decade, especially when we look at what took place in the following years, however unlike many other musicians in the early 1930s, he was one of the lucky ones that was still able to make a living from music during the Great Depression.

Coming out of the Let’s Dance program, in 1935 Goodman and his band went on a national tour that would change the trajectory of jazz forever. After a number of less than ideal engagements where the band had to play the uninspired popular music of the time, the morale of the band was at an all time low. That all changed though when they got to California. You see, the time slot Goodman filled on the Let’s Dance broadcast was far too late for the average east coast listener. As a result, many of the audiences wanted to hear the popular music of the day, with it being quite likely that almost none of the white audiences were actually aware of the hot jazz sound that had developed in New York in the previous decade and that Goodman’s band had been performing regularly. However with the time difference to the west coast, Goodman had started to amass a younger audience that was aware of this new type of music. Thinking that the tour would mark the end of the band, when they arrived at the Palomar Ballroom in Los Angeles, Goodman and the other musicians decided to play the music they enjoyed the most, the hot jazz arrangements of Henderson. Supposedly, the audience erupted and what was only meant to be a short stint at the venue was extended due to popularity.

While this was only one event in music history, it does signify something much larger: that hot jazz was popular among the younger generation. Most likely due to Goodman being a white musician and being able to broadcast hot jazz to an audience that typically didn’t listen to black radio, he exposed that jazz was a universal music that could be enjoyed across racial lines. As such, the performance at the Palomar Ballroom is often seen as the official start to the Swing Era and ushered in over a decade of popularity jazz had never experienced before, and has yet to experience again.

After the tour, Goodman’s national profile skyrocketed and he became one of the most popular musicians of the decade. In his shadow were hundreds of other bands, all fighting for a share of the ever increasing performance opportunities. In an age where so many bands were working, those that stood out were the ones with a unique sound. Goodman’s trademark was his virtuosic clarinet playing backed by arrangements that followed the Don Redman/Fletcher Henderson/Horace Henderson/Benny Carter approach first established by the Henderson band in the Jazz Age. Initially, every other band emulated the sound and made the innovative experimentations of the Henderson band a stereotypical trope. But over time, outliers emerged with their own sounds, creating an elaborate tapestry of characteristics that ultimately defined the sound of the Swing Era.

The word swing had already been present in musical circles for a number of years with it being used in titles such as Duke Ellington’s It Don’t Mean A Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing) in 1932. However, somewhere in the 30s it caught on as the universal name for jazz. How exactly each artist thought of themselves, we may never know, but we do know that some like Glenn Miller didn’t associate with being a jazz musician and considered himself an entertainer. Others like Ellington most likely would have seen themselves as a jazz musician but whether they viewed the popular works of the era as prime examples of jazz is a different story.

To help navigate an unfathomable amount of music from the Swing Era, I’ve split this resource into two categories. Up first are the common characteristics that were shared among many of the bands, then for the second half I’ve highlighted a couple of the major bands and explored unique aspects to each of their sounds. While the scope of covering the Swing Era is extraordinarily large, I’ve tried to summarize as much as possible into this entry so that you can come away with a strong understanding of the techniques used. Where possible I’ve included bits and pieces of history to help provide context, but as so many of the characteristics were shared across dozens of bands, you’ll find this entry leans a little more on the technical side of things, especially in the upcoming section. So let’s dive in and get to the good stuff!

Common Ground

Like most things in life, the music of the Swing Era didn’t simply come out of nowhere. In fact, many of the major characteristics were established by the Henderson band over 1924 to 1931 by combining the sounds of Chicago, New York, and Kansas City. I go into considerable detail in the previous resource on the Jazz Age about these characteristics but here’s a quick run down. By 1934, the following were common:

Bands were made up of 2 or 3 trumpets, 1 or 2 trombones, 3 or 4 reeds (could double on all saxes and clarinet), piano, guitar, upright bass, and drums

Typically the brass and reeds are split into two distinct sections with unique lines

A higher degree of syncopation in the horn parts

An abundance of riffs, particularly played over moving chord changes

A variety of sections, including intros, interludes, melody statements, and solos

Horn backgrounds behind solos were generally either riffs or pads

It was common to highlight individual sections to have the melody, a precursor to the instrumental soli

The harmony included the common conventions of Western popular music as well as a few other techniques such as the dom7#5 chord, passing diminished chords, bVI, chromatic approach chords, and the occasional whole tone passage

Horn sections were voiced in closed position block voicings

The most popular time feel was a driving four feel with the bass walking, the hi-hats keeping time, the piano either playing stride or playing more sporadically, and the guitar playing on all four beats

Pieces were beginning to have a slow fade out by the band

As mentioned earlier, this model moved from Henderson’s band to Goodman’s, establishing the foundation for every other swing band. However there were many more techniques which became commonplace too. One of which actually came from outside the world of hot jazz and drew from sweet music.

Sweet Music

Although there were multiple popular genres of music in the 1920s, the one which received widespread attention from white audiences was sweet music. The style itself was a much tamer, watered down version of hot jazz which had considerably more in common with traditional Western dance music of the 1800s than the innovations of New Orleans at the turn of the century. At a time where racial lines extended to music, sweet music offered a white alternative to hot jazz, stripping back most of the unique characteristics found in black American music so that it was socially acceptable to listen to by white audiences. Of course there were still white bands that recorded hot jazz, but hot jazz itself was primarily a young person’s music and sweet music was able to appeal to older audiences as it had more in common with traditional music styles.

Arguably creating the entire style, Paul Whiteman was the biggest artist associated with sweet music. While he definitely strayed from the Early Jazz approach, Whiteman initially started his band in 1920 with the idea of merging jazz with orchestral music in what he deemed “symphonic jazz.” His intent was to deemphasize improvisation and bring more attention to the arrangement, removing the chaotic nature of Early Jazz with the cleanliness of a classical approach. Quite quickly this concept caught fire and launched Whiteman into popularity. So much so that he became the best known American musician in the 20s and was supposedly earning close to a million dollars per year. To be expected, once Whiteman had exposed a new type of popular music many tried to follow in his footsteps, thus creating the sweet music category.

At the start of Whiteman’s recording career the sound of the band had far more in line with classical than jazz. However as the 1920s progressed the band started to emulate more of the hot jazz sound, albeit in a considerably more restricted manner. Where hot jazz offered syncopation and individualistic interpretations, sweet music was considerably more mellow and drew heavily from classical music traditions. Listening back to some of the Whiteman recordings today, the music represents a wide spectrum of influences with jazz only being one of them. Depending on the particular track, you can hear characteristics of marches, minstrel/vaudeville shows, opera, and of course the romantic period of classical music. Some of Whiteman’s major hits included Whispering in 1920, Pickin’ Cotton in 1928, Marianne in 1929, and if you want to hear his collaborations with Bing Crosby I’d suggest starting with Louise from 1929.

Notably for the music of the Swing Era, sweet music established a category of dance music that lived on into the 30s and 40s through the presence of songs from Tin Pan Alley and Hollywood that drew deeply from the sweet music tradition. Moreover, sweet music informed the sentimental vocal approach of singers like Bing Crosby which was then emulated by Tommy Dorsey on the trombone. There’s much that can be said about the influence of sweet music but probably the most notable characteristic that comes up time and time again in the Swing Era is the wide and fast approach to playing vibrato.

Likely being inspired by the bel canto opera vocal tradition of the 19th century, sweet music very much had an obsession with exaggerated vibrato. Although you can hear the approach on numerous records by different artists, one name reigns supreme and that is the popular band leader Guy Lombardo. Have a listen to You’re Driving Me Crazy recorded in 1930 and you’ll see what I mean.

Obviously enough of the American audience liked the sound for it to be ported across to big band swing in the 30s. As Goodman was quite familiar with sweet music, having helped establish the style as a sideman on many recordings as well as having had to satisfy certain record demands with his own band, it is natural to see how such fast and wide vibrato was incorporated quickly in his band. However, if you listen to other artists such as Henderson, you can see that the Lombardo approach to vibrato had started influencing the band at least as early as 1931. Prior to that year, the most common approach for vibrato in a hot jazz setting was a short burst in a similar manner established by Louis Armstrong in the 20s.

Mutes

Moving on from the influence of sweet music, another major sound of the Swing Era was the use of mutes in the brass section. First established by King Oliver in the early decades of the 20th century, straight mutes had become a standard texture in the Jazz Age. However, by the time the 30s came around, mute manufacturers were producing even more options that slowly began to be incorporated into the sound of large ensemble jazz. Alongside the straight mute, the cup mute and derby hat mute became popular alternatives, offering more unique textures for arrangers to draw from.

For many, the straight mute still reigned supreme with its shrill, bright, and metallic tone which offered a stark contrast to the sound of the woodwinds. However, some arrangers such as the trumpeter Buck Clayton, helped establish a new tradition by using the cup mute. In comparison, the cup mute offers a much warmer sound due to its mushroom like design and build materials. At first it is likely that the mute became popular through individuals using it for solos which then led to its use in full sections. A fantastic example of this is Clayton’s melody on Topsy recorded by Basie in 1937. It is uncertain exactly when the cup transitioned to being used by a whole section but by the 1940s it was a prominent feature in many Swing Era bands. Arranger Buster Harding provides a fantastic model with his arrangement of 9:20 Special released by Basie in 1941.

Topsy

Eddie Durham

9:20 Special

Arranged by Buster Harding

Prior to the cup mutes popularity though, another mute had already begun being implemented in the big band. Coming out of the experimentations of musicians like Oliver in the early 1900s, instead of inserting specific items into the bell of a brass instrument, they also used various objects to cover the bell such as hats. Initially this was used for two reasons: to create a wah-wah sound by changing the amount the hat covered the bell, and also to dampen the sound. The effect caught on and by the mid 1930s an official mute in the shape of a derby hat had been created by a manufacturer due to the popularity of the sound. While it is hard to locate a specific point in time where it transitioned into widespread use by full brass sections, the word “hat” is marked on Henderson scores from the first half of the 1930s such as his arrangement of Happy As The Day Is Long. However, when comparing the score with the recording, it seems that the hats ended up not being used

As there was considerably more freedom with the hat mute due to it being held and not inserted into the instrument, musicians could get a wide range of timbres from the single mute. The most common was to alternate an open and closed position (marked by an “o” for open and “+” for closed), either on a long held note to give a wah sound or on alternating notes. However, having the hat strictly in a closed position did dampen the sound considerably and was an early equivalent to the bucket mute we have today. Although it would be possible to show an example of the hat mute using the open and closed notation, a similar mute was also in use in the 30s which demonstrates the audible effect in a far more exaggerated manner.

Originating as a household plumbing tool, the plunger mute had been a popular device since the start of jazz thanks to Oliver. Although it was used by others, by far the most popular association with the mute came from the Ellington band with trumpeter Bubber Miley evolving the techniques established by Oliver. Eventually this led to Cootie Williams and “Tricky Sam” Nanton taking the sound further in their own approaches. Due to the sound of the plunger being such an integral part of Ellington’s “jungle sound,” it is no surprise that he also started to incorporate the mute into the brass section of his band, with one of the standout examples being “It Don’t Mean A Thing” released in 1932.

It Don’t Mean A Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing)

Duke Ellington

Lastly, one other mute which wasn’t as extensively used in swing music but was starting to creep into big band orchestration was the harmon mute. For the most part, the “wah wah” mute as it was known then was primarily a solo device used as an alternative to the plunger mute. While I have never come across a recording from the 1930s with a full brass section using the harmon mute, I’m sure there are examples somewhere as the technique had been established as early as 1925 in the compositions and arrangements of Ferde Grofé for the Whiteman orchestra. At the time the standard convention was to play the mute with the stem in, giving a much more tinny, novelty sound compared to the considerably more popular stem out version established in the coming decades.

Huckleberry Finn, Mississippi Suite Mvmt. 2

Ferde Grofé

Embellishments

Ever since the start of jazz, musicians have been looking to add more personality into their parts. In earlier resources I’ve explored how this was achieved through adding syncopation and blue notes to the music, however it was also common for musicians to use various embellishments too. Like all major jazz techniques, these embellishments started off as improvisational devices which slowly started to be incorporated into the mainstream ensemble approach in the late 1920s and early 30s. Interestingly, after looking at a number of Henderson’s handwritten parts, it is clear that any form of articulation or embellishment was rarely written into his arrangements even though they appear in the associated recordings. Unfortunately, without seeing examples from all of the major arrangers it is hard to know whether this was commonplace across the board or just something specific to Henderson. However, by the emergence of the Swing Era, markings did start carrying across into the sheet music and were more widely used in big bands.

To specify, when I use the term embellishments I am referring to techniques such as glissandos, shakes, turns, scoops, falls, bends, and plops. All of which became considerably more common and part of the vocabulary of swing arranging in the 1930s. One of the best examples of multiple embellishments being utilized in the same piece is King Porter Stomp originally recorded by the Henderson band in 1928, revised and recorded again in 1933, and then later slightly reworked for Goodman in 1935. Many of the devices can be heard in all three versions but in my opinion the 1933 recording is by far the most exciting.

King Porter Stomp

Arranged by Fletcher Henderson

Shout Sections

In addition to being a fantastic example for embellishments, Henderson’s arrangement of King Porter Stomp also made use of a new type of section right at the end of the recording. Instead of simply repeating the melody or concluding with an outro, the new approach was to have the pinnacle of an entire arrangement at the end of the piece and utilize the upper register of the horns where possible. To begin with, these sections were heavily inspired by riffs suggesting that the concept began with territory bands in the heavily blues influenced Midwest. Somewhere along the line the technique picked up the “shout” section name, most likely to describe the sound of the brass in their upper register. Since Louis Armstrong had come onto the scene, the top note of the trumpet had consistently been challenged and by the Swing Era it had reached as high as concert Eb above the staff.

Interestingly, other than riffs being written in the upper register of the trumpet, there wasn’t much that differentiated a traditional shout section from any other sort of riff passage. Both sections featured blues based riffs, and when multiple voices were layered on top of each other they either played unique riffs or were organized in a call and response format. Some great examples of Swing Era shouts include Tain’t What You Do (It’s The Way You Do It) recorded in 1939 by Jimmie Lunceford, One O’Clock Jump by Count Basie in 1937, and Flying Home by Lionel Hampton in 1942.

One O’Clock Jump

Count Basie

Instrumentation

Similar to the expansion of band sizes in the Jazz Age, the Swing Era saw even more bands add more instruments to their ranks. At the start of the period the norm was to see two or three trumpets, one or two trombones, and three or four reeds alongside a typical four piece rhythm section. However, by the end of the 1940s, the typical big band had four trumpets, three or four trombones, and five saxophones, with a rhythm section. No single bandleader established this final format first, with each one adding personnel over the course of a decade. Some standouts include Ellington and Lunceford who pioneered the use of the baritone sax as a fifth reed, while others like Miller expanded the trombone section from three to four.

Perhaps more importantly to the music was the evolution in jazz drumming that took place from the late 1920s and throughout the 30s. Up until then, the drums sounded quite different to what we now associate with the instrument. The two main components were the snare and bass drum, with the latter being the primary pulse keeping device. As we unpacked in the previous resource, the 20s saw the creation of the sock cymbal, a set of cymbals that rested on the ground and were played by the foot. The end of the decade saw the cymbal be elevated to waist height through the use of a cymbal stand but still retained a pedal to allow the cymbal to be opened and closed by the foot. Initially the cymbal was used in a similar manner to how it had previously, reinforcing the back beat and specific accents. But with the shift off the floor, drummers were able to now play the cymbal with their sticks and experiment with new patterns. As a result, the primary time keeping device on the drums shifted from the bass drum to the hi-hat and changed the entire sound of the instrument.

With less reliance on the bass drum, the approach to playing that particular drum also changed. As the hi-hat was seen as the metronome, the bass drum could be played much lighter and in a supportive role to the bassist. Due to there being no amplification for rhythm section instruments at the time, the new method gave the impression that the acoustic upright bass was actually louder as it reinforced some of the same low frequencies. Like most things in life, the name for this particular approach came later on and we now call it “feathering” the bass drum.

Shifting back to the hi-hat, due to the ability to open and close the cymbal with the foot pedal, drummers were able to create a number of different tones. Quite quickly two of the preferred techniques included keeping the cymbal firmly closed, and alternating between open and closed on the classic quarter note/crotchet and two eighth note/quaver rhythm. While you can hear multiple drummers experiment with the hi-hats over the course of the late 20s and early 30s, historians credit “Papa” Jo Jones as being one of the major figures behind playing the hi-hat. A fantastic example of Jones playing on the hats is Basie’s One O’Clock Jump from 1937 where he shows a number of different approaches.

One O’Clock Jump

Count Basie

Another notable evolution of the drums was the use of toms. Initially brought over by Chinese immigrants to the United States in the 1800s, the drum found its way into the drum kit in the early 20th century. It was originally used by American musicians for musical gimmicks but in the 1920s a select few jazz bands started experimenting with it in their lineup. Namely, Henderson and Ellington. While both writers didn’t utilize the sound to an extensive degree, there are examples from as early as 1924 with toms present such as Shanghai Shuffle where they were likely used to help bring an “oriental flare” to the music.

Just under a decade later though, American manufacturers started innovating with the design of toms, moving away from the tacked on skins and creating a new system of tunable heads with metal hoops thanks to the feedback of Gene Krupa. With the new toms in hand, Krupa then utilized them more so than any other jazz drummer up to that point. Similar to how the hi-hats became the main time keeping device for the drum kit, Krupa experimented with emphasizing the time feel on the toms. It is hard to know exactly when he started this process, but one thing we know for sure is that his new approach took the world by storm with the release of Goodman’s version of Sing, Sing, Sing in 1937. It also probably helped that this particular tune was the first extended drum solo in recorded history.

Sing, Sing, Sing

Arranged by Jimmy Mundy

Having a buffet of musical techniques at their disposal, Swing Era arrangers made the most out of the situation by experimenting with orchestration and textures where possible. For the most part, many of the experimentations didn’t stray too far from the Henderson/Goodman model, only going so far to group certain sections with another instrument or pairing a number of individual timbres together. However, that still amounted to a sizable number of variations, far too many to analyze in a resource such as this. Instead, what I would suggest is familiarizing yourself with the original techniques and sounds utilized by the Henderson band in the early 30s and compare that model with a few Swing Era recordings to see what is similar and what differs. What you’ll find is that many of the differences come from applying the various sounds that we have just explored. If you find anything that I haven’t mentioned here, let me know and I’ll likely add it to the resource.

Common Styles & Repertoire

The last area worth covering is the large variety of styles that big bands in the Swing Era performed. At the time, instead of simply thinking of all music as being swing, there were multiple subcategories which existed within the genre. Some of which drew from the hot jazz tradition, while others were influenced by the sweet music. Most bands, both black and white, catered to as many audiences as possible resulting in their libraries including a mixture of pop tunes, sentimental vocals, novelty songs, swing instrumentals, and latin influenced charts. Between all of the categories, many of the techniques behind the arrangements were the same as what we have already explored, with the differences coming from the tempo, lyrics, origin of the song, or musical gimmicks that were considered funny at the time. For example, pop tunes represented music from Tin Pan Alley and Hollywood and catered toward audiences who perhaps found hot jazz too confrontational. A great example of the pop category is Tu-Li-Tulip Time recorded by Jimmy Dorsey and the Andrews Sisters in 1938.

Moving to the sentimental vocals category, these are exactly what you might expect: vocal ballads which highlighted the new crooning style. One of the most popular vocalists of the time was Bing Crosby and through many collaborations with big band leaders, there are countless recordings of him singing sentimental ballads. I Wished On The Moon recorded in 1935 alongside the Dorsey Brothers band is one such example.

Unfortunately when it comes to novelty songs it can be hard to relate to the tropes that audiences in the 30s would have found funny. As a result, it can be difficult to know exactly what arrangements may have been classified in the category. In general the comedic element came from the topics discussed in the lyrics, so even if a band performed an instrumental variation of a given novelty song it would fall into the category by association. It was also common for these types of songs to make use of musical gimmicks as interjections that paired with the lyrics. One of the more popular novelty hits of the Swing Era came out of Kay Kyser in 1939 titled Three Little Fishies (Itty Bitty Poo).

Arguably the most familiar these days are the swing instrumentals as they have been able to stand the test of time (so far) and still be remembered many generations later. Almost all of the examples we have looked at in this entry fall into the category and include classics such as Sing, Sing, Sing and One O’Clock Jump.

To round up the five main categories we have the charts with a latin influence. Unlike the other four, this particular category does have musical differences to the typical swing approach, namely in the rhythm section feel and with the addition of a number of common latin rhythms in the horn parts. I’ll save a complete investigation into this category for a different resource but for now the main takeaway is that due to the influence of Cuban music in the 1920s, specifically the son style, many bands in the United States included arrangements trying to emulate the sound. Of course, almost all of these weren’t that authentic, but out of the obsession with Cuban music came a whole new category of music for big bands to play. Arguably the most famous band leader playing in this category was Xavier Cugat who actually was the first person to record Cole Porter’s Begin the Beguine in 1935.

As you can see, music of the Swing Era had a number of amazing characteristics that helped differentiate it from previous periods. However, we’re not done just yet. Now that we have established the foundation for most ensembles of the time, it is time to do a deeper dive into the music of a select few bands to show just how much differentiation actually existed between them. In order to keep this resource from turning into an epic novel, I’ve restricted my analysis to four main artists: Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Tommy Dorsey, and Glenn Miller. My intention is that by exploring four of the most popular artists of the time, you will get a better understanding of the Swing Era sound that most people associate with the period today.

One quick note before wrapping up this section. Alongside everything we have just unpacked, there were also harmonic and improvisational developments which took place in the Swing Era. For the most part, many of the solos and chord progressions were similar to the Jazz Age, however the small changes that did take place helped set up the next big phase in jazz history. For that reason, I’ve chosen to leave the topic of harmony to the end of this resource. So don’t worry, we’ll get there eventually but you’ll have to wait a little longer.

Duke Ellington

Coming out of the Jazz Age, Ellington had garnered significant popularity across the country through his residency at the Cotton Club and their weekly broadcasts. Continuing on into the 1930s, his band was given multiple opportunities to tour both nationally and abroad, as well as consistent recording contracts. It was a very prosperous time for Ellington and arguably the Swing Era was when Ellington wrote his most well known works.

Interestingly, Ellington was somewhat of an outlier when it came to the swing movement, focusing on his own individual approach to music rather than bending to the will of the masses. Of course he still entertained some of the swing era tropes, but when looking at his output between 1930 to 1950, a majority of his works actually don’t sound similar to any other band and is likely one of the reasons he is remembered so fondly today. Similar to what we unpacked in the previous resource, Ellington continued to explore new ideas well into the Swing Era, albeit at a slightly slower pace than his earlier years. He was still prolific in his output but his focus had changed to expanding large ensemble jazz beyond the three minute window that recording technology allowed. In other words, he wanted to write longer works that dealt with more complex subject matter. And you know what, he did just that while also churning out staggering shorter compositions at an alarming rate.

While there are many unique aspects to all of his compositions, across the hundreds that he wrote in the Swing Era alone, he pushed the harmonic language of jazz further than it had gone before. Concepts such as bitonality, chord alterations, and non-diatonic shapes made their way into Ellington’s music, receiving mixed opinions from critics such as in the case of Reminiscing in Tempo and Black, Brown and Beige. Unfortunately at the cost of pursuing art instead of commercial success, those that fell in love with hits such as Koko and Cottontail often were perplexed by the direction Ellington took in other more harmonically complex compositions. However it didn’t seem to impact Ellington’s overall trajectory, as he was able to retain engagements consistently throughout the Swing Era. In this section we’ll specifically be focusing on these harmonic advances and dissect a number of examples to reveal how he used each technique before looking at a few other characteristics of his Swing Era sound.

Up first is Reminiscing in Tempo, a harmonic tour de force which showcases a whole slew of techniques that were not used by other jazz composers/arrangers at the time. To do the piece justice it would take far too much space in this resource as there are so many interesting choices that Ellington made, however one that always seems to catch my attention is a set of chromatic major triads that float over a pedal bass note about two and a half minutes into the work. This particular technique, which is now often referred to as abstract harmony or slash chords, very much pushes diatonicism out the window and to see Ellington use it in 1935 is quite surprising. It may in fact be one of the earliest examples of the technique in the big band tradition as it only became a common part of jazz vocabulary decades later.

Reminiscing In Tempo

Duke Ellington

One person that must be mentioned when discussing this period is Billy Strayhorn, someone who helped shape the sound of the Ellington band from the late 30s all the way to the second half of the 60s. Many of his contributions became staples of the band’s sound such as compositions like Take The A Train, Lush Life, and Chelsea Bridge. In particular, Chelsea Bridge likely drew inspiration from impressionist composers such as Debussy, with non-diatonic harmony being used immediately in Ellington’s four bar introduction. Having the harmony move in unrelated maj7 chords and then the chord progression of the melody move between parallel minmaj7 chords was unheard of in jazz at the time. Similar to the abstract harmony in Reminiscing in Tempo, these impressionistic lydian sounds with ambiguous key centers really did not become mainstream until pianists such as Bill Evans became a prominent force in the 50s and 60s. Once again showing just how progressive Ellington’s approach to harmony really was.

Chelsea Bridge

Billy Strayhorn

Before moving on, one last example of Ellington’s harmonic explorations can be found in Dusk recorded in 1940. Most of the chord progression follows in line with the standard Swing Era approach, however a few particular instances stand out. Ellington makes use of a number of chord colors which are quite uncommon for the period such as the dom7b5, dom7b9, min11, and maj7. Additionally, in one particular passage he uses a set of secondary dominant chords in quick succession to create an incredible amount of chromatic movement. While secondary dominants were not new at the time, using the technique so often in a single bar is often more associated with writers like Thad Jones decades later.

Dusk

Duke Ellington

Aside from Ellington’s harmonic explorations, one of the most impactful shifts in his sound came from the addition of bassist Jimmy Blanton in 1939. Although Blanton’s stay in the band was cut short due to complications with tuberculosis that eventually led to his passing in 1942, the young bassist redefined the instrument through his melodic approach which paved the way for future generations of jazz bassists. By changing how he plucked the string, he was able to achieve more sustain out of the instrument, giving the bass a new prominent sound in Ellington’s band. He also paired this technique with a strong understanding of harmony and improvisation, allowing him to transform the bass from purely an accompanying role to a soloist in the jazz setting. As Ellington did with the many individuals in his ensemble, he made use of Blanton’s abilities in his compositions and started highlighting the bass as a solo instrument, even going as far as placing Blanton in front of the entire ensemble when performing. While Blanton’s stay in the band was unfortunately quite short due to illness, he left a tremendous mark with recordings such as Jack The Bear and Koko in 1940.

Up until this point we’ve primarily focused on how Ellington broke away from the swing mold, creating his own path and redefining the big band landscape. But even Ellington couldn’t help including some of the popular characteristics of the period into his own music. With that said, his approach always sounded refreshing compared to his contemporaries and when you line up a chart such as Old King Dooji against many of the examples covered earlier in this resource, it still sounds like an outlier in comparison. Interestingly, the chart is saturated with unison sax lines and riffs throughout but written in such a way that it never quite feels like the standard riff approach. There’s unique interplay between sections and the harmony has surprises around each corner. Personally, I feel like Old King Dooji refreshes the stereotypes of the swing genre and demonstrates how a composer can put their own spin on a Swing Era chart while still utilizing the standard swing vocabulary.

Old King Dooji

Duke Ellington

Unlike every other band leader of the time, by pursuing his own approach and not following the swing crowd, Ellington was able to not only maintain popularity through the Swing Era but also was one of the only bandleaders to survive in the following years after the interest in swing music faded. He went on to continue to write many more outstanding works, including the impressive multimovement suites such as the Far East Suite, Such Sweet Thunder, and the score for Anatomy of a Murder as well countless other compositions. His contributions to jazz cannot be ignored and while I’ve only gone over some of the major highlights of his Swing Era sound, you could spend years analyzing just the music from this period.

Count Basie

Offering a completely different perspective on the Swing Era sound is Count Basie and his orchestra. After Benny Moten’s passing in 1935, Basie decided to form a new 9-piece band and invited a number of his old Moten bandmates to join him. Performing in Kansas City the following year, one evening John Hammond (the same individual who connected Goodman and Henderson together) heard the Basie band on a live radio broadcast playing in New York and fell in love with their sound. Hammond reached out to Basie and invited the band to the east coast as well as helped expand the ensemble to the conventional 13-piece big band size at the time.

When Basie’s band started out, his ensemble very much reflected the characteristics of the Kansas City sound and primarily performed head arrangements. Unlike the bands on the east coast which relied on arrangers, head arrangements were often composed on the spot without sheet music by members of the band improvising riffs and harmonizing them. They also prioritized extended solos with the rhythm section playing a driving jump feel. A fantastic example of this format was the Basie theme song One O’Clock Jump.

With the expansion of the band, Basie joined the ranks of the many other east coast groups that used written arrangements. The sheer size of the band as well as the demands of the engagements they played required more musical organization than head-arrangements could offer. Fortunately Basie had an ace in the hole by hiring Eddie Durham, the previous arranger for the Moten band. Not only was Durham well versed in writing for big bands on the east coast but his time in Kansas City made him familiar with the Midwestern approach to jazz, allowing the early arrangements of the Basie band to merge the two musical worlds together seamlessly.

Durham got to work immediately and in 1937 contributed standout charts such as Topsy which helped establish the new Basie sound. Unlike many of the Swing Era charts, Topsy gives considerably more time to individual solos, favoring the spontaneity of improvisation over heavily arranged band sections. Riffs can be found almost everywhere but presented in a slightly more refined manner compared to the traditional head-arrangement. Most importantly, the recording showcases the driving Kansas City rhythm section feel created by Basie on piano, Freddie Green on guitar, Walter Page on bass, and “Papa” Jo Jones on drums. This particular approach became the staple for the Basie sound, providing enough of a unique sound for the band to carve a space in the local scene.

Unlike the Redman approach to splitting the reeds and brass, Durham often used all of the horns together on a single harmonized melody line. While this technique had been used earlier by Whiteman as well as sparse examples in the Henderson band a decade earlier, it was definitely not as common as the Redman approach to split the reeds and brass into two designated parts. You can hear this effect in Topsy but for a better example, John’s Idea recorded in 1937 featured the technique throughout the entire arrangement.

John’s Idea

Eddie Durham

The Basie band at this time also had two modes when it came to dynamics, either loud or soft, with most sections being the former. However, in the early recordings you can clearly hear them change between the two dynamics suddenly, almost as a way to surprise the listener. If you’re a fan of the Basie band of later decades then this technique won’t be that much of a surprise to you but it is interesting to note that even in the 30s that the band was engaging in subito dynamics.

In the coming years many arrangers wrote for the band, eventually landing on a powerhouse duo in the early 1940s of Buck Clayton and Buster Harding. In the years between when Durham's first charts for Basie arrived in 1937 and when the first recordings of Clayton and Harding’s arrangements started to emerge in 1941 and 42, the band had undergone a serious harmonic transition. Initially, the Basie sound prioritized the blues and harmonic simplicity, but through arrangers such as Andy Gibson and Tab Smith, the band started to pick up similar colors to the other New York groups. By the time Harding penned 9:20 Special for Basie in 1941, the band was used to playing colorful chord voicings and progressions filled with chromatic harmony, however they still featured blues heavy tunes too. Some fantastic examples of both approaches colliding include Clayton’s Avenue C and Red Bank Boogie.

It should also be noted that in Rusty Dusty Blues recorded in 1942, Harding showcased double time phrases in the horn parts, a technique which had yet to become commonplace in Swing Era writing. However, musicians would have been familiar with the idea as it had been a staple in jazz improvisation for close to 20 years at the time.

Rusty Dusty Blues

Arranged by Buster Harding

One final aspect worthy of mention are the piano interludes that Basie himself contributed to the band. Present in many of the recordings, these stride and boogie woogie inspired solos were just as significant to the ensemble's sound as any other characteristic we’ve covered. When looking across the entirety of Basie’s Swing Era recordings, it is clear that he reuses the same riffs in his solo passages in the later years. Here are just a few of the most common.

Unfortunately, in the second half of the 1940s Basie had to break up his band, most likely due to the decline in popularity of swing music. There are however a number of rumors about the band’s end that suggest it may have actually been caused by Basie’s poor management of money, but we will likely never know the exact reason why. What we do know though, is that Basie went on to run a smaller band for a couple of years before being convinced to start another big band in the 1950s. For many, the later lineup is what they think of when they hear the Basie name due to the critically acclaimed recordings in the late 50s and 60s. As such, the earlier ensemble pre 1950s is often referred to as the “Old Testament” band, with the latter being the “New Testament” to help differentiate between the two. While a comparative analysis of both bands would be fascinating, that will have to wait for a different day as that would take us out of the Swing Era and there is still plenty more to discuss.

Before moving on, it is important to be aware that both Basie and Ellington were part of the highest echelon of black big bands in the Swing Era. There were, however, considerably more names in the same category with other notable mentions being Cab Calloway, Chick Webb, and Jimmie Lunceford. Due to the time these musicians lived in, life was not as glamorous as it may seem when looking back. Segregation and racism was abundant in the United States and could be felt both in New York and elsewhere. Black bands were never given the same representation that white bands of the time received and were never compensated to the same degree. Often better residencies and engagements would be reserved for white bands, forcing many artists to tour extensively for very little money. This alone led to the collapse of almost all of the black bands by the end of the 40s while somehow still making their white managers wealthy. When all of the avenues for income such as radio, touring, and local engagements required going through white administrators, it is a surprise bands like Basie’s didn’t disband sooner, but I think that is more representative of just how popular swing music was at the time.

The next two leaders we are about to unpack were on the other end of the spectrum and led white ensembles which enjoyed tremendous success and became household names. Interestingly, neither of them considered themselves jazz musicians, both starting their careers as sweet music session musicians and viewing their own ensembles as dance bands. These days they often get a bad reputation as their music represents a different demographic of the Swing Era that hasn’t aged as well in modern jazz circles, but they are worthy of discussion and were prominent musical forces at the time. More so to the point of this resource, when the average person thinks of the swing sound, they often think of these artists or at least the well known songs associated with them. If we want to accurately capture that sound in our writing, we must at least be aware of the techniques that contributed to it, which means broadening the scope of our understanding and including both prominent white and black artists.

Tommy Dorsey

Picking back up with the sweet music of the 1920s, trombonist Tommy Dorsey quickly established himself as a prominent trombone player in the Pennsylvania music scene during his teenage years. As a 22 year old he had already been a member of prominent groups such as the California Ramblers and Paul Whiteman’s orchestra when he decided to form his own band with his older brother Jimmy in 1928.

The early sound of the Dorsey Brothers band definitely provides quite the contrast when compared to recordings of the same year by Henderson. Where some tracks show a quasi representation of the hot jazz approach such as Round Evening, others like Evening Star have far more in common with sweet music. Both however, still include many of the same characteristics of the Henderson band in the Jazz Age, albeit with a completely different feeling. Moving past the sweet music characteristics, one important factor of these early recordings is that they demonstrate Dorsey’s initial approach to playing the trombone and you can hear his prominent lyric ballad style starting to emerge.

In later recordings it is clear that the Dorsey’s had been influenced by the emerging swing music of the 1930s. Tracks such as Mood Hollywood and Shim Sham Shimmy recorded in 1933 almost sound like they could have been played by Henderson a few years earlier and feature a similar rhythmic lilt. Just by listening to the trumpet solos you can tell that the influence of Louis Armstrong played a major role in the ensemble's overall approach to playing swing music.

Unfortunately, over the years a divide started to emerge between the brothers resulting in Tommy going his own way in 1935. That same year he decided to run his own dance band, drawing on inspiration from the Lunceford band while also pushing himself as a feature soloist. It was in this band that Dorsey became known for his approach to playing ballads on the trombone, demonstrating incredible control in the upper register and producing a smooth tone. While there are many examples over the life of the band of his trombone playing, a great example is Tea for Two recorded in 1939.

Dorsey must have still been inspired by the Lunceford sound by 1940, as he was able to hire one of the chief arrangers for Lunceford, Sy Oliver, to start writing for his band. Alongside Oliver, two other notable additions joined the band, the drummer Buddy Rich and the vocalist Frank Sinatra. With the new members came a new approach for the band, namely the more jazz orientated writing of Oliver and executed by Rich, as well as Sinatra’s romantic vocal style which was paired with arrangements by Axel Stordahl. It is from this particular period that most of Dorsey’s hits were recorded such as Opus No.1, In The Blue Of Evening, and I’ll Never Smile Again.

The evolution of the band from 1935 to the 40s is staggering. Similar to when Goodman picked up Henderson five years earlier, Oliver provided a direct link to the jazz tradition to the white band. Opus No. 1 swings just as hard as any of the other reputable bands of the time and is a stellar arrangement by Oliver. While the Dorsey band doesn’t really bring anything new to the swing department, they do provide a fantastic insight into a dance band that could play on both sides of the fence so to speak. Although it may have taken years to develop, by the 1940s the band could easily pass as one of the best bands when it came to swing numbers while also equally executing on ballads and popular songs.

Following the influence of other white band leaders at the time such as Harry James, the Dorsey band expanded to include strings in 1942 by hiring the recently released string section from Artie Shaw's band. Combining the expressive strings with the powerful full bodied brass, Dorsey’s signature velvet tone, and Sinatra’s hauntingly intimate vocals, led to a winning formula that sold millions of copies. Stordahl’s arrangements of In The Blue Of Evening may just be one of the most beautiful ballads from the entire Swing Era. By pairing lush string pads with muted brass textures and clarinets, he was able to create a beautiful bed for both Dorsey and Sinatra to sit on top of. I’ll save a full analysis of Stordahl’s approach for a later resource as it deserves more room than simply a brief mention with Dorsey and is an important part of the lineage of arrangements in the crooner tradition.

Only a few years later, in 1946, Dorsey broke up his band following the end of WWII but a year later decided to reform the ensemble due to the popularity of a compilation album he released in 1947. The band would stay together for another nine years until Dorsey passed away. Although they did achieve some level of attention in these final years, the group would never see the same level of fame they had acquired in the early 40s.

Other than leading one of the premiere white ensembles of the Swing Era, Dorsey was also important for another reason. During his career he helped establish a young trombonist by the name of Glenn Miller, first by employing him in the Dorsey brothers band in 1934, and then again in 1938 when he gave money to Miller to start his own ensemble. If it weren't for this second action the world may never have experienced some of the most iconic music of the Swing Era.

Glenn Miller

Similar to the story of many musicians, Glenn Miller picked up the trombone as an adolescent and never looked back. During his teenage years, Miller was known to pick up gigs around town with local dance bands. This continued through his entire high school life and even into his tertiary studies, deciding to drop out from the University of Colorado and pursue a career in music. Inevitably, in 1928 he ended up in New York City via a two year stint in the Los Angeles based Ben Pollack band. Miller established himself quickly as a session musician and rose through the ranks to play on sweet music recordings alongside the likes of Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey. However, he wasn’t just a trombonist and had spent many of the years between 1928 and 1937 writing arrangements for a variety of artists too.

Eventually he came to the decision to branch off from being a sideman and start his own orchestra in 1937. Unfortunately, this first attempt lasted less than a year due to not having a signature sound for the band. However, Miller learnt from the experience and came back in 1938 with a new set of arranging techniques which ultimately would define his entire career. Likely being influenced by the sound of both Ellington’s mood music and Gene Gifford of the Casa Loma Orchestra, he first found success with recordings such as Moonlight Serenade, Little Brown Jug, and Sunrise Serenade in 1939. Similar to other popular white bands of the time, he merged the swing sound of Goodman with the popular repertoire of musical theatre and Hollywood, creating an irresistible mixture that took the world by storm. It also helped that he arranged these numbers, alongside a handful of original compositions, with a number of unique techniques that helped him stand out among the hordes of other bands.

Miller’s new sound was heavily defined by a handful of textures that were consistently reorganized in each arrangement. By limiting the techniques he used, he was able to establish an entire library of hits while only making use of a small number of approaches. One of his most popular options was a unique orchestration for his 5-piece reed section, using a clarinet lead with two altos and two tenors. Within this framework he would double the lead clarinet an octave lower on the second tenor and then fill out the harmony in between. In some cases this would result in the tenor being placed in the upper range of the instrument, contributing another unique element to the overall sound.

Moonlight Serenade

Glenn Miller

Another interesting reed texture Miller utilized was having two clarinets and two tenor saxes in octaves. Instead of the typical closed position voicing, the clarinets would play the melody and a harmony line with the two tenor saxes doubling the same exact lines down an octave. A fantastic example of this can be found in Sunrise Serenade.

Sunrise Serenade

Glenn Miller

Moving over to the brass section, one of Miller’s go-to textures was using the straight mute. While not unique to Miller, many of his classic hits such as Moonlight Serenade utilized the effect and make it worth mentioning. The brightness offered by the mute contrasted beautifully with the smooth sounds of the band and provided a unique counterpoint which was both prominent but also supportive. Alongside the straight mute the derby hat mute was also commonly used, particularly the alternating open and closed sound heard at the beginning of On A Little Street In Singapore.

Moonlight Serenade

Glenn Miller

On A Little Street In Singapore

Glenn Miller

These techniques, among others, came together to form the basis of the Miller sound. Although each sound could stand alone, the major factor which led to Miller’s success was how he utilized them together. Instead of sitting out on a single technique for too long, he would often only utilize one sound for a brief period before swapping to a new texture. Going a step further, each texture was often associated with a dynamic level, creating interesting ebbs and flows in the music which helped keep the listener engaged. When compared to other bandleaders of the Swing Era, Miller definitely prioritized the use of dynamics more than others and was a standout when it came to creatively employing them across his arrangements. This type of contrast alongside a level of simplicity in his arrangements and performed with a light feel all contributed to the winning formula which allowed Miller to soar above the competition.

When WWII rolled around, Miller actually decided to give up his band in order to join the military. While there he helped establish a new type of military band to entertain the troops which actually still continues on today as the highly respected Airmen of Note. Unfortunately, in 1944 Miller disappeared without a trace after boarding a plane from England to France and left his incredible legacy behind. No one knows exactly what happened but one thing we know for sure is that he was never seen again.

Things To Come

We’ve made it! Well almost. As you can tell there’s a lot that can be said when looking at the Swing Era. Jazz took the world by storm and could be heard everywhere but at the expense of its popularity, it started to lose many of the qualities that defined the artform to begin with. By the end of the period the sound of swing could easily be boiled down to a set list of characteristics, as we’ve unpacked throughout the resource, instead of championing the individuality of the performers/writers. That doesn’t mean the music lacked any sort of quality, it was just different and more formulaic compared to what could be heard in the Jazz Age. Some musicians stood as exceptions, namely Ellington, but the majority succumbed to the pressures of popular culture. However, this transition didn’t go unnoticed.

As the Swing Era took place over more than a decade, a new generation of black American musicians had started to come up through the dance bands and grew sick and tired of the nightly routine of playing uninspired music to the masses. Somewhere along the line, the bands had become equivalent to a day job and no longer stimulated the musicians that played in them. They yearned for jazz to return closer to the traditions that had come before, prioritizing individual expression and artistic intent over the opinions of the audience. But what happened is a story for another time, for now we have some other business to attend to that provides a fantastic bridge into the developments of jazz after the Swing Era.

So far in this resource we’ve looked at many of the major characteristics of music between 1935 and 1945 but have missed one specific area: harmony. For the most part, Swing Era harmony matched the developments seen in The Jazz Age with no new major additions making their way into written arrangements. Of course Ellington was the main outlier in this department, constantly experimenting with new chords and voicings as we saw earlier, but these new sounds never really influenced the other bands of the era. Instead, the main place the harmony started to shift was through the notes musicians would outline in their improvisations.

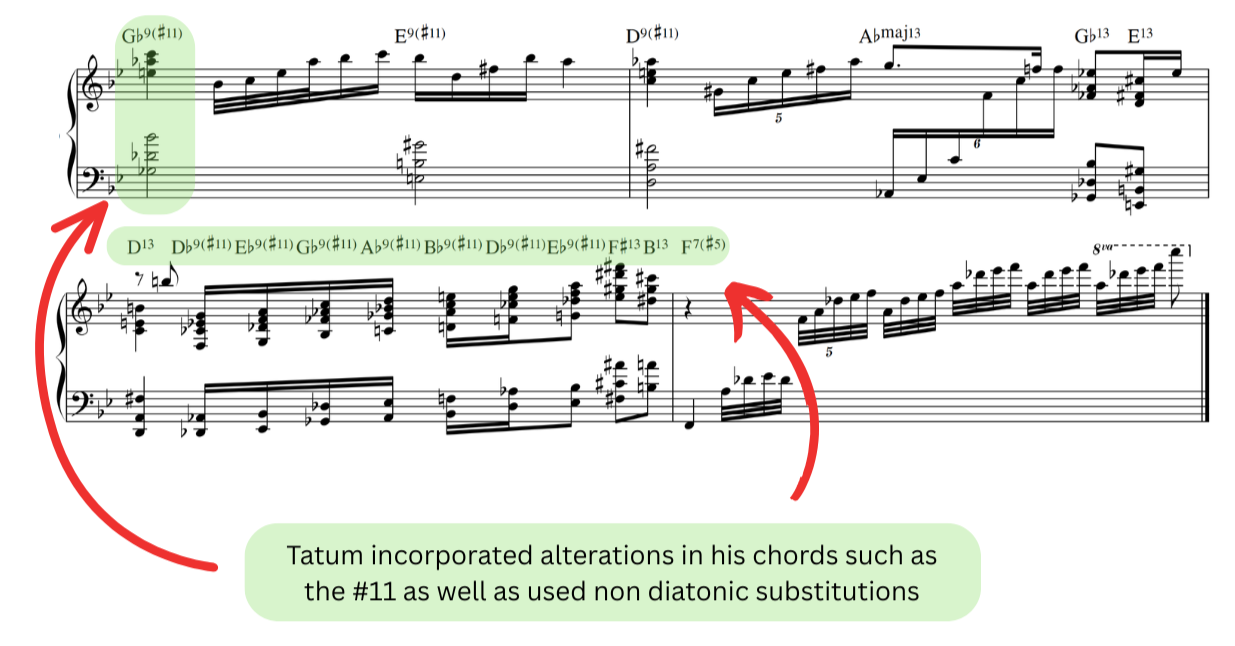

While musicians such as Lester Young, Howard McGhee, Roy Eldridge, and Coleman Hawkins all began incorporating new chromatic notes such as the b9 and b13 into their solos, all of them paled in comparison to the level of harmonic sophistication displayed by pianist Art Tatum in the 1930s. Years before substitution and complex chord structures became the norm in jazz, Tatum demonstrated it all in his solo piano recordings. Over the course of the decade he recorded numerous examples of altered chords, #11s, and quite modern reharmonizations that definitely were ahead of his time. Take a look at this fantastic introduction to Tiger Rag recorded in 1933, one of the first solo recordings he ever made.

Tiger Rag

Arranged by Art Tatum

Like most innovators, it took musicians a long time to catch up to Tatum and replicate the harmony he had mastered in the 30s. However, that didn’t stop others from trying, especially the eager new generation of musicians entering the scene. While no one came close to Tatum, some elements of his more advanced harmonic concepts did start being incorporated into arrangements. One such example is Pickin’ The Cabbage written by a young Dizzy Gillespie in 1940 for the Cab Calloway band. Straight out of the gate we hear a #11 voiced at the top of the horn section paired with chromatic moving harmony, a definite statement by the 23 year old.

Pickin’ The Cabbage

Dizzy Gillespie

Although none of these harmonic developments really affected the sound of the Swing Era, they were setting the scene for something much greater. A new take on jazz which moved in a completely different direction and was created primarily by an underground group of young musicians. A style of great importance to the history of jazz and a musical movement which would redefine the artform forever. However, we’ve run out of room in this resource so that topic will have to be covered next time.

The Takeaway

The Swing Era represents the golden period for jazz arranging. A time where those who could write for big band were in high demand and had the opportunity to create trademark sounds for the bandleaders that hired them. The period was filled with hundreds of groups, all competing for the best gigs and recording deals, with only a handful being lucky enough to sit at the top of the pecking order. However, the increase in popularity in jazz led to the watering down of many of the original elements and replaced them with repetitive, formulaic sounds due to the sheer amount of arrangements needed to satisfy the evergrowing audience. In one way, this actually makes replicating the sounds of the Swing Era far easier for modern day writers but has also pushed some critics to classify swing music as part of the pop music category more so than within the jazz lineage. Personally, I love the music and associate it with some of my fondest musical memories. As I now pursue a life as a jazz arranger, the period has even more significance, representing a foundational period for the history of my chosen occupation.

Up next we explore the style which redefined everything about jazz. Changing gears from the world of the arranger to the world of the improviser and analyze how a number of different musicians came together to create bebop.