The Musical Characteristics That Changed

Bebop Into Hardbop

When it comes to my journey with jazz, hardbop is a style I personally relate to more than any other and I think it’s safe to say a lot of people share the same view. While it wasn’t the first form of jazz that I came across, hardbop was introduced to me fairly early on and has definitely impacted my musical taste for the last two decades. At the same time as I was playing the Glenn Miller classics in high school, some of my friends put me onto Moanin’ by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, and it was love at first sight. Something about the sound of that track just seemed to align with me and ever since, hardbop albums have been some of my most played records.

Like many people, my journey started with Blakey, but then quickly expanded to the many musicians that worked in his band. Lee Morgan, Wayne Shorter, Horace Silver, Hank Mobley, and countless others, all who went off and released their own amazing hardbop inspired albums after working with the Jazz Messengers. However, at the time of discovering all of this music, I really wasn’t paying that much attention to any of the unifying qualities these artists shared, nor how I could try to replicate them in my writing. I even ran my own hardbop band and played some of the classics, and later on was commissioned to transcribe a few dozen tracks for a friend. Unfortunately, through all of that I was still an onlooker and hadn’t really started to understand what made hardbop different from bebop or anything that came later.

While at university the status quo for teaching hardbop was that it was just a slower, harder hitting form of bebop. Although somewhat true, with that point of reference you should be able to take a tune like Confirmation and simply make it sound like hardbop by only changing two aspects. And if you’re like me and have tried that, you’ll know that it just results in a slower form of bebop and doesn’t necessarily capture the spirit of either style. Somewhat ashamedly, it actually wasn’t until I started researching for this particular resource that I was able to understand exactly why hardbop came about and could articulate the specific qualities required to make an arrangement feel authentic for the style.

After reading a number of books and articles, it became clear that one of the key factors was the development of Rhythm and Blues and its influence on jazz. Interestingly, R&B is a style that is not often given much thought in tertiary jazz courses as it marks one of the major splits from jazz and is seen more closely with Rock ’n’ Roll in music history. However, by understanding the musical changes that led to R&B, as well as some of the style’s characteristics, it’s a lot easier to see how hardbop came about and differentiated itself from previous jazz styles. To save you having to look into R&B elsewhere, in this resource I spend a bit of time unpacking the style, enough so you can hopefully see the impact it had on the trajectory of jazz and formation of hardbop but not quite a full deep-dive like other styles I’ve covered. But before we get there, it might be helpful to first establish what hardbop is so that everyone has a clear picture of the style to begin with.

What Is Hardbop?

When listening to artists such as Art Blakey or Horace Silver, it can be pretty easy to say that they fit within the hardbop sound. However, what exactly is hardbop and is it only restricted to the artists which sound like the Jazz Messengers? Interestingly, the style embraces a significant number of musicians over the 1950s and the first half of the 60s, with a number of identifiable subcategories. One of the more well represented areas are those who sound similar to the Jazz Messengers and draw heavily from both R&B and bebop vocabulary. Whereas others such as Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Charles Mingus also fall under the umbrella of hardbop even though they sound completely different.

As such, defining the style can be quite difficult due to the broad parameters of all of these artists. Just by looking at Miles’ career in the fifteen or so years that hardbop inhabits shows an incredibly wide range of playing styles that would be impossible to capture under the hardbop banner. Now when you expand the viewpoint to include the quickly changing sounds and careers of at least a dozen other popular hardbop artists of the time, the lines are blurred even further making it almost impossible for a consistent definition to be found. Depending on your background and how you were introduced to the style, you’ll most likely have a different perception of what hardbop sounds like. For me, I strongly associate it with the driving swing of the Jazz Messengers. For others, it may be Miles’ first great quintet on albums such as Relaxin’ or Mingus’ Ah Um. Thanks to the loose parameters of the style, all of these are correct even though they all sound completely different to one another.

Now it wouldn’t be too helpful if I didn't at least attempt to provide a definition in this resource but hopefully by establishing some level of context you can see how difficult it can be to establish a clear set of terms that define the style (and hopefully you’ll forgive me if you don’t necessarily agree with what I’m about to say). In order to understand the similarities between such a wide pool of artists and music, one must zoom out slightly to find common ground. For the most part, the primary definition of hardbop is music that was built off of the foundations of bebop but with a more palatable approach that focused on melody rather than technical complexity. Many achieved that by playing at slower tempos and incorporating simpler chord progressions with a higher emphasis on the blues. A considerably large group of musicians incorporated elements of R&B such as a driving backbeat, but not all, making the “hard” hitting style of Blakey not a requirement for the hardbop sound. It should also be mentioned that hardbop was predominantly created by black Americans as opposed to Cool Jazz which was mainly white.

Due to the extremely diverse range of artists associated with the style, for the sake of this resource I’ve opted to focus on the musicians that make up the stereotypical hardbop sound. Specifically, those that were involved with the Jazz Messengers or shared similar approaches. That way those of you who are looking to recreate that particular sound will be able to come out of this resource with the necessary techniques to do so. It would be quite difficult to do justice to all of the amazing talent that existed in that period and realistically, I believe that it would be better to explore each individually in their own resource instead of a collective resource such as this one. So I’ll save that for the future, for now it’s time to talk about R&B.

A New Direction

During the mid 1940s, when bebop was emerging as a new artform and the big bands had spent a decade in the limelight, changes began to take place in the music industry. Thanks to the economic conditions of WWII, swing musicians were able to demand incredibly high prices for performances, however like all bubbles, the big band craze was unsustainable. With the end of rationing, the general public was once again free to spend their money however they pleased and that meant a decrease in revenue for large venues. Many of the popular white big bands had become accustomed to being paid incredibly well and in response to the decline were reluctant to lower their fees. Unable to find a compromise, big bands quickly were replaced by smaller ensembles who tried to emulate the swing feeling to various extents.

While this was the story for white big bands, due to the segregated conditions of 1940s America, black bands faced considerably harsher treatment and were blocked out of many of the better paying venues. By the start of the decade, black bands had already started to break up and by the time the prosperous white bands finally started to collapse, there were very few black large ensembles left. Many turned to other alternatives, and for Louis Jordan he decided to lead a six piece ensemble called the Tympany Five. Building off of the popular dance styles of the day, Jordan created a new variation of jazz which focused more on the blues and the Midwestern riff style (most commonly associated with the early Count Basie band). It captured all of the excitement of swing music but was able to deliver it with a much smaller ensemble, something which would eventually give the band an edge when the big band bubble burst.

Interestingly, another notable shift was taking place in black communities around the United States that would lead to Jordan becoming nationally renowned. As we looked at in the resource covering the Jazz Age, at the beginning of the 20th century, black Americans were able to establish a new level of economic success leading to the creation of a black middle class in certain parts of the country. Alongside this development came the side-effect of wanting to distance themselves from any sort of slave related culture such as the blues. However, by the late 1940s, the view on the blues was once again changing and now was being upheld as a significant pillar of black American culture. Due to Jordan’s music being built off of the blues and blues related genres such as boogie woogie, his recordings skyrocketed in popularity in the later half of the 1940s.

Like most new music, Jordan’s recordings weren’t immediately associated with a particular title. Due to being a black artist, his music was initially released under the “race” category, meaning that Jordan’s new format was matched up against jazz, gospel, blues and a wide variety of other types of entertainment such as black vaudeville acts and recorded sermons. However, in 1949 the term “race records” was replaced with the name Rhythm and Blues, which inevitably started to be associated with the most popular black artists of the time. Thanks to this change in marketing by the record labels, a new style was born and Jordan became the model for future R&B artists.

When listening to the various hits of Jordan and His Tympany Five, it becomes clear that there wasn’t too much difference between the band’s approach and that of the riff based dance bands of the Swing Era. Almost all of the recordings feature the sound of the blues, some level of boogie woogie type piano accompaniment and arpeggiated bass line, riffs in the horns, a strong triplet swing feel, and a noticeable emphasis on the backbeat. However, one of the biggest differences was the vocal part which captured a lot more of these characteristics than previous styles and often pairs them with comedic lyrics. Eventually Jordan would also add electric guitar and electric organ, giving his approach even more unique qualities. A great example is Choo Choo Ch’Boogie released in 1946 and Saturday Night Fish Fry in 1949.

Choo Choo Ch’Boogie

Arr. by Louis Jordan

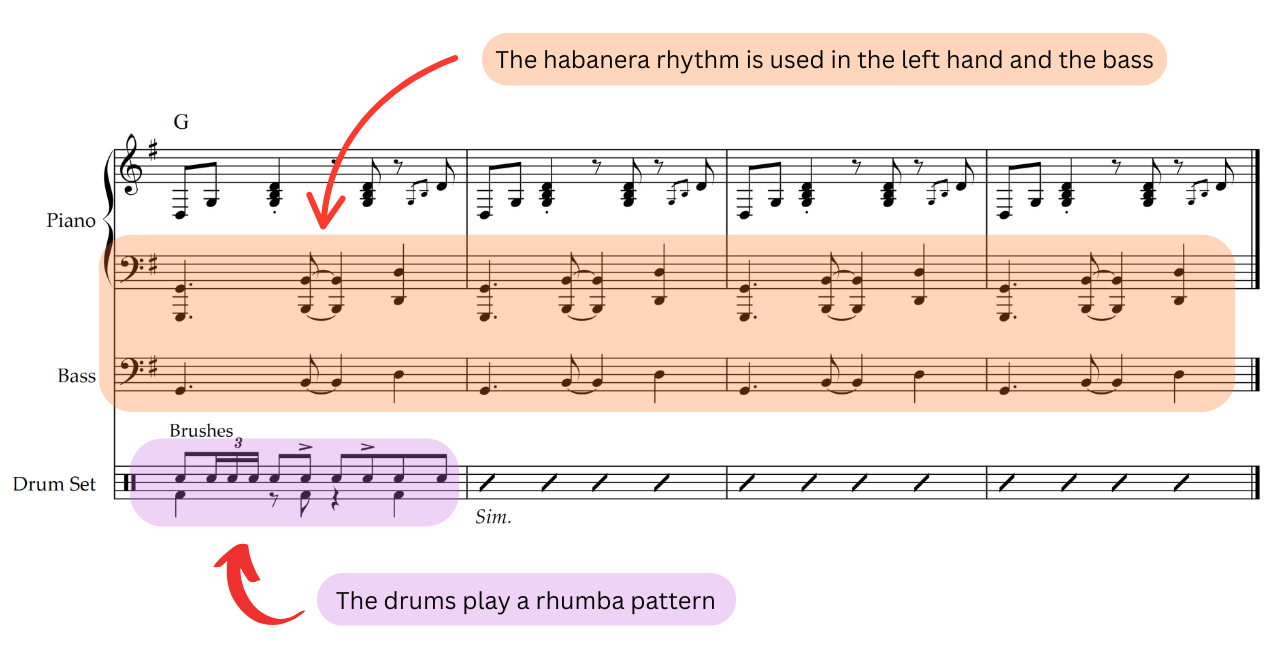

Jordan wasn’t the only artist playing this type of music, with others like the Ink Spots, Hal Singer, and Big Jay McNeeley’s Blue Jays all contributing to the new style. Notably, by the end of the 40s two R&B artists from New Orleans were also making their mark with a slightly different take. Alongside the heavy blues and boogie woogie influence already established, Professor Longhair and Fats Domino incorporated elements of Afro-Caribbean rhythms into their music. In tracks such as Hey Little Girl released in 1949, Longhair utilizes a habanera rhythm in the bass line as well as a rhumba pattern in the drums. Collectively they give the piece a signature sound and add a new dimension to R&B.

Hey Little Girl

Professor Longhair

By the start of the 1950s, three major subcategories had emerged, those which followed the jump sound of Jordan, the New Orleans inspired music, and the newly emerging doo-wop vocal groups. Initially, all three favored a heavy blues feel but over the decade R&B started to be influenced more directly from gospel music, with artists such as Ray Charles and Sam Cooke eventually creating another new style called soul music. However, that is a topic for a different day and for the sake of this resource the main takeaway is that R&B rose out of the decline of the Swing Era as the popular music for black communities, not bebop. As a result, a new generation of jazz musicians were growing up influenced by R&B which inevitably impacted the music they created.

Miles & Silver

Coming into the 1950s, jazz was in an interesting place. Swing had lost its popularity, bebop had alienated many with its complete overhaul of musical characteristics, and cool hadn’t really been established outside of a small group of musicians. Unfortunately, bebop had also hit a ceiling musically. Although the style was built around innovation, it had now been developed for close to a decade and like all great musical styles, the qualities that once made it feel refreshing were now becoming stale. In order for jazz to progress, some kind of musical evolution had to take place.

Like so many major breakthroughs in jazz history, it is no surprise that Miles Davis was at the forefront of the shift. Having just completed the famous nonet recordings which sparked the start of cool jazz at the end of the 40s, Miles was looking to push the music in yet another direction. Over the first few years of the 50s, he recorded a number of times, each slowly shifting the dynamic of bebop into something completely different. And then, in 1954, after kicking his drug habit and moving back to New York, he went into the studio with an all-star cast of musicians including J.J. Johnson, Lucky Thompson, Horace Silver, Percy Heath, and Kenny Clarke to record two tracks. The first was Blues'n'Boogie, a Gillespie tune which was straight out of the bebop handbook, however the second side was Walkin’ which many argue is the first hardbop track ever created.

Walkin’

Miles Davis

Afterwards, Miles went on to record a number of different sessions built around a similar premise but often without the heavy blues influence. Most notable are those with what is considered his “first great quintet,” which included John Coltrane, Red Garland, “Philly Joe” Jones, and Paul Chambers, such as the classic Cookin’, Relaxin’, Workin’, and Steamin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet. Due to signing with Columbia and wanting to exit his contract with Prestige, these four particular albums were recorded quite quickly alongside the quintet’s busy performing schedule and are one of the closest representations we have today to what the group would have sounded like live. While Miles was instrumental in the formation of hardbop, for many, including myself, he only marks the start of the style with others carrying the torch further.

It would be impossible to talk about hardbop without spending a significant amount of time discussing Horace Silver and his legacy. Having grown up in Connecticut learning piano from a church organist and with a mother who sang in the church choir, Silver was influenced by gospel music from an early age. Along the way he was also inspired by many of the jazz greats as well as a whole slew of blues pianists such as Avery Parish as well as those who played with Muddy Waters, Lightning Hopkins, and Peetie Wheatstraw. Collectively, each of these different sounds came together to create Silver’s own unique approach to playing the piano and in 1950 at the age of 22 he was picked up by Stan Getz. A year later, he relocated to New York and quickly became one of the most in-demand pianists in the jazz scene.

By 1954, alongside being a busy sideman on sessions such as the recording of Walkin’ with Miles, Silver was running his own group with saxophonist Hank Mobley and bassist Doug Watkins when he was approached by the Blue Note label to put together his own quintet for a recording session. As a result, he picked up Kenny Dorham on trumpet and Art Blakey on drums and made jazz history over the course of two different recording dates. The name of the group, “The Jazz Messengers,” came from Blakey who had been using it for a mixture of ensembles up until that point. But from then on, the name would heavily be associated with the sound established in those early Silver recordings and go down to be one of the most popular hardbop ensembles of all time.

At that point in Silver’s career, he had already recorded twice under his own name but both were primarily made up of bebop inspired tracks. However, with his third entry into the studio with a fresh sounding quintet he broke new ground and reinforced the sounds heard earlier in 1954 with Miles’ Walkin’. Of special note was the track The Preacher which departed completely from bebop and was inspired by a classic gospel number titled Show Me The Way To Go Home. Other than having a blues influenced melody, the soloists approached the changes by blending bebop and blues/gospel together to give an infectious and new sound to jazz. While Miles definitely improvised in a melodic way on Walkin’, the language used on that particular recording by all of the soloists was far closer to bebop than the blues, whereas on The Preacher it was the other way around. It is also worth mentioning that in these early recordings of the Jazz Messengers we see the start of the iconic trumpet and tenor sax frontline that would go on to be a staple for jazz ensembles for coming decades.

1954 was a tremendous year for jazz and between the recordings of Miles and Silver the foundations of hardbop were laid. But the developments of the new style weren’t limited to just the heavily blues inspired sound and melodic approach found on The Preacher and Walkin’. In the years after, both Blakey and Silver took hardbop to new heights and established the sound further. Over the course of numerous albums, the style started to have definitive qualities that helped differentiate it from bebop. The most notable were:

Heavy use of minor keys/modes

Slower tempos

Strong rhythmic patterns

Blues and gospel influenced phrasing and compositions

Afro-Caribbean influences, particularly in the rhythm section

Simplistic melodies

Many of these qualities can be traced back to the influence of R&B with only a few coming from other places, specifically, the Afro-Caribbean patterns. While they were found to a level in the New Orleans form of R&B as well as to a lesser extent in other R&B tracks in the mid 50s, the influence most likely came from two other locations. The first being the background of Silver’s father who came from the Cape Verdean Islands, as well as Blakey’s two year stay in West Africa. However, it is more likely that the influence actually came from the emerging Latin Jazz scene in New York in the 40s and 50s. Thanks to the collaborations between Dizzy Gillespie and Chano Pozo, as well as the formation of Machito’s Afro Cubans, a model for incorporating Afro-Caribbean rhythms into jazz had already been established years prior. However the rhythms made their way into hardbop, by the second half of the 1950s they were a permanent feature of many of the compositions.

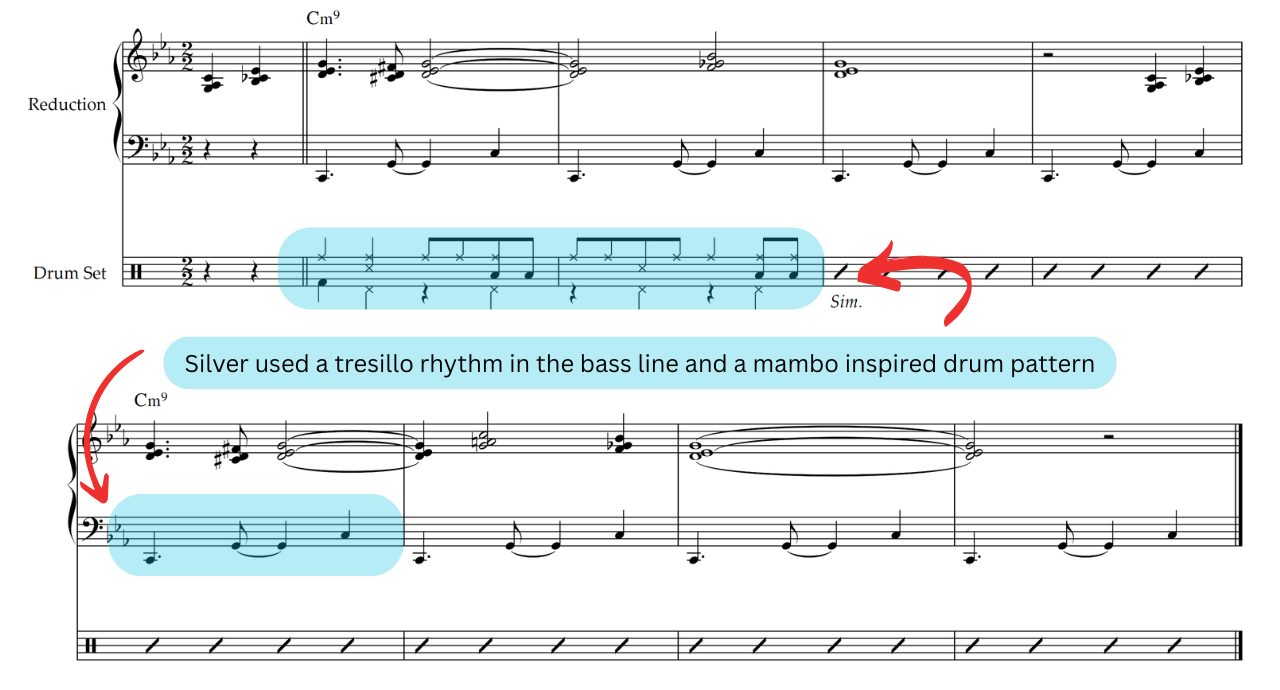

Nutville

Horace Silver

Alongside the interesting new accompanying rhythms, the method behind horn voicings broke from the traditional bebop route of harmonizing lines in unison and octaves into multiple other directions. In Silver’s Señor Blues released in 1956, he embraced a number of different voicings such as traditional 3rds and 6ths as well as quartal shapes. When paired with his stacked 4ths in the piano, it gave the piece a distinct harmonic sound which felt drastically different to other hardbop pieces.

Señor Blues

Horace Silver

Other composers such as Benny Golson, Hank Mobley, and Wayne Shorter took horn voicings further with both the 2-horn and 3-horn format of the Jazz Messengers. Building off of the sound of Tadd Dameron’s sextet in the late 40s, these arrangers used a variety of approaches alongside the traditional triadic shapes that had been the norm in earlier forms of jazz. One popular option was to use non-traditional shapes that could only be justified through chord tone allocation rather than the relationship between each of the notes. Instead of voicing a 3rd or a 6th away from the melody note, they would instead look at how the melody related to the underlying harmony and then voice out one or two other notes that would best capture the quality of the chord. For example, on a C7 chord if the melody was a Bb, then one voice would be allocated to an E and another to some sort of color tone.

Lady Bird

Tadd Dameron

This Is For Albert

Wayne Shorter

All of these aspects came together to create a new approach to jazz that became considerably more popular than bebop. While hardbop never quite obtained the national recognition that R&B received, it still bolstered enough sales to support a wide range of artists. Outside of Miles, Silver, and Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, there were a number of other notable hardbop artists such as Clifford Brown, Sonny Rollins, and Charles Mingus, not to mention many more. Each had a certain approach to the style, taking particular elements we’ve discussed as well as implementing some of their own along the way. It really was an exciting time for jazz and is still seen as one of the more popular periods of jazz history today.

The Takeaway

Due to a number of critical events, whether it be the place of blues in the black American community, the rise of R&B, the decline of the Swing Era, or a whole handful of other factors, hardbop emerged as the new direction of jazz in the 1950s. It took the best elements of bebop, refined them into a new style, and re-emphasized components of other African American musical styles to create a new model for jazz to come. But it didn’t stick around for long because the 1950s was a fertile period for creativity and the music was already shifting by the second half of the decade. Led once again by Miles, jazz took a turn away from harmonic complexity to focus specifically on the sound of a singular chord change. However, you’ll need to read more about that in the next resource which covers Modal Jazz.