The Key To Emulating

The Jazz Age Sound

When it comes to jazz history one era often gets neglected, well at least I didn’t give it much light until recently and I imagine that many others also fall into the same boat. The Jazz Age, specifically the period of the 1920s through to about 1935, marks a special time in jazz history between the creation of the artform and when it became known by everyone in the western world. It was a time where artists were highly adventurous and everyone had their own defined sound. Interestingly, the Jazz Age was also when the world was introduced to the big band and with it, the jazz arranger. Musicians such as Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, Louis Armstrong, and a whole slew of others, exploded onto the scene with their own bands and rewrote all of the musical characteristics established with Early Jazz. It must have been an exciting time and one that deserves a place alongside every other major era of jazz history.

Surprisingly, as someone who has pursued jazz arranging for well over a decade now, almost all of my journey has somehow avoided interacting with the Jazz Age. Most of the introductory arranging techniques I learnt while at university were taught through examples from the 1950s and onward, and I had only really gone as far back as the Swing Era (1935-45 or so) with my listening. That was until one day I was influenced by something a little more unconventional for a jazz musician, the video game Cuphead.

Just before the world closed down in 2020 due to COVID-19, I was putting together ideas for my youth program, trying to program fun music that the students would find relevant but also fit the big band lineup. I decided on a video game based project and quickly realized I wouldn’t have enough time to write all of the arrangements for the first rehearsal. In a manic dash, I quickly scowled the internet to see if there was any video game music written for big band and stumbled across Cuphead. In case you are unaware of the game, the game was a passion project between two brothers (as well as a small indie team) based around the animation style of the 1930s, also known as rubber hose animation (think Steamboat Willie). Alongside the animation they decided to have an authentic big band soundtrack filled with compositions in a similar vein to those from the Jazz Age. The project was a huge success and became one of the biggest games of 2017, but more importantly to my situation, they had published scores and parts for the entire soundtrack online which I could use with my youth band.

The youth band project came and went, but I couldn’t stop thinking about the style of music the Cuphead soundtrack used. It seemed somewhat familiar, with links to classic big band songs like Sing, Sing, Sing yet a little more raw. In the process of putting together the concert I was actually able to get in contact with the composer, Kristofer Maddigan, and we exchanged a few emails. I learnt that he originally had no background in jazz arranging and had spent two years researching music from that era in order to compose the soundtrack. One of his go-to resources at the time was Gunther Schuller’s Early Jazz, which proved a great starting point for my own research journey.

Shortly after completing the book I realized that a lot of the scores Schuller mentioned were actually available at various archives around the country. So instead of trying to navigate transcribing tracks that came from a time when recording quality wasn’t that great, I descended on the Smithsonian to see what I could get my hands on. It is one thing to listen to a track on repeat and something completely different to do so with the original handwritten score in front of you. While Schuller had primarily used his own transcriptions to create his arguments in Early Jazz, I could now see exactly what each of the composers and arrangers were doing. My mind was blown. Here I was, an arranger in the 21st century thinking that I knew a thing or two about big band history, realizing that all of the main techniques I used were actually developed by people like Don Redman back in the 20s and not later arrangers like Neal Hefti or Sammy Nestico. The entire research process was eye opening and I have now grown to appreciate the music of the Jazz Age as being some of the most interesting and influential big band music in history.

That’s where this resource comes in. It seems in the world of jazz that the artists from the 1950s are far more universally known than those that came before. However, I want to show you just how amazing the previous generation was and how they established the sounds which went on to become famous in the coming decades. If you’re starting in a place with no knowledge about the Jazz Age, then names like Don Redman or Eddie Durham may not sound familiar, but hopefully by the end of this resource you’ll have fallen in love with their music and see just how pivotal it was to the history of jazz.

This particular entry is designed to continue the conversation from my previous resource on Early Jazz, however in a slightly different manner. The Jazz Age specifically featured a number of artists who all had a unique approach to the music they performed. As they became more popular, their innovations were copied by others and eventually led to the creation of a completely new form of jazz altogether. In this resource, I’ve decided to look at a few of the key artists of the time and explore how they went about crafting their sound. While there were ample amounts of artists to choose from, I've specifically chosen only the most influential in order to demonstrate the major shifts that took place. Unfortunately when writing a resource such as this, certain artists and techniques will be missed, but it has been my goal to explore the era thoroughly enough so that you can hopefully recreate the sounds authentically in your own writing. With that said, let’s start exploring the Jazz Age!

The State Of Jazz In 1920

When we discuss jazz history it’s important to understand that the music wasn’t created in a vacuum but directly reflected the living conditions and culture of the people that created it. As such, we must acknowledge that Early Jazz was primarily created by black Americans, a minority group who went through extreme hardship and mistreatment for much of the history of the United States. Early Jazz itself was a result of their experiences and as the decades progressed, jazz shifted to reflect the changing views of black Americans. In order to understand exactly how the artform changed it is essential that we also understand the social changes that took place in the early 20th century.

As we explored in the previous resource, there was a notable movement of African Americans around the United States with the abolishment of slavery. The newly emancipated people left their old life in rural locations and moved to urban centers, bringing with them their various influences and cultures which eventually led to the creation of Early Jazz. Unfortunately, as the South went through the Reconstruction era, segregation laws nicknamed “Jim Crow Laws” were created to limit black American’s rights. While racism was still present all across the country, in the southern states these laws were strictly enforced, making the life of all black Americans considerably more difficult than their white counterparts. To put it in perspective, some historians have said that this particular period of history was actually far worse for African Americans than slavery. When the opportunity to work elsewhere in the country presented itself with the manufacturing boom post World War I, a national movement took place (now called the Great Migration) with millions of black Americans leaving the South in hopes for a better life. As a result, large black communities started to emerge in cities such as Chicago and New York. Similarly to the movement that brought freed slaves to urban centers, the Great Migration also played a large role in the development of jazz, particularly in these large ethnic enclaves around the country.

Notably, musicians from New Orleans started to move to Chicago, with one of the most significant being Joe “King” Oliver. He brought with him his signature New Orleans approach to Early Jazz and after establishing a new ensemble in the city, sent an invitation to his protege Louis Armstrong to join him. At the age of 20, Armstrong moved to Chicago to follow in the footsteps of Oliver, a move which started a set of events that drastically changed the course of jazz. Not only did Armstrong master Oliver’s approach, he started to innovate and experiment with a number of different techniques. He pushed the range of the trumpet higher, moved beyond embellishing the melody to actually start improvising in his solos, prominently played with a legato approach, and helped impose a normalized swing feel among many other contributions. Inevitably, Armstrong left Oliver’s band and pursued other avenues, helping to spread his new approach across the country, but more on that later.

One important aspect to remember when looking back at the 1920s is that jazz was primarily a localized music. For many decades the music itself had been restricted to places such as New Orleans and the small number of New Orleans musicians who toured across the country. Once the first jazz recordings were released in 1917 with the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, the country went through a small period where everyone loved the new music, however the national audience quickly moved to the Blues craze in the 20s and Early Jazz faded into the background once again. Other than the musicians in Chicago, there was a growing jazz culture on the East coast created by a new generation that had received formal music education. As a result, the music took on a different flavor and morphed into a new variation of jazz. The same could be said about other midwestern locations like Kansas City, where the popularity of ragtime and the blues generated another alternative to the Chicago/New Orleans approach. Jazz itself wasn’t restricted to just these three cities but many of the key innovations from the 1920s and early 30s came from artists in these locations.

The Jazz Age was an exciting time, with the music being pushed in multiple new directions. As a localized artform, cities, towns, and individual bands all had drastically different individual voices, each of which contributed to jazz in a unique way. While each band had their differences, one factor which united them all over the 20s and 30s was a gradual expansion of ensemble size. Saxophones and more brass joined the ranks. Some instruments were replaced by others, such as the tuba giving its position to the upright bass and the banjo to the guitar, while approaches on all instruments collectively evolved. It can be hard to map exactly when each change took place but we do know that by the mid 1930s all of them unified to redefine the national image of jazz, however I’ll save that for another time. Most importantly, the Jazz Age is where jazz arranging became a profession. Having more musicians in a band created a need for written arrangements in order to organize everyone together, and like all new artforms, in the beginning there were no official rules or techniques to go by. Thanks to the experimentation of people like Fletcher Henderson, Don Redman, Benny Carter, Duke Ellington, and a whole slew of others, a new tradition emerged, one which I’m proud to be a part of a century later. To help cover the wide range of characteristics from this era, I’ve split this resource into three sections, representing the three major cities discussed earlier and the musicians and sounds associated with each scene. Up first is Chicago!

Chicago

Being one of the largest hubs for black Americans in the country, South Chicago started attracting black residents of New Orleans right from the start of the Great Migration. However, most musicians chose to stay in the Crescent City until the mid 1910s as the local scene still yielded a plethora of work. At first it was players like Jelly Roll Morton who left but in late 1917 with the closure of Storyville, many more would make the long train journey north. One of which was Joe “King” Oliver, who when offered two different invitations to join bands in Chicago in 1918, left promptly and didn’t look back.

After a number of years in his new home, Oliver formed his own ensemble, notably bringing Armstrong from New Orleans to play second cornet in the new organization. Fortunately for us, the band was able to record a number of times, giving us an idea of what their approach to jazz sounded like in the 1920s. At the time these recordings fell into a larger classification of music called “hot,” a label used to differentiate jazz before it had an official name. Most prominent jazz artists from the period belonged to the category with the key defining characteristic being the tempo or energy they brought to the music. As the decade progressed, the term shifted from describing a whole demographic of jazz to a specific approach to improvisation, so much so that you can see it handwritten in a number of early jazz arrangements.

For most scholars the recordings of King Oliver from the 20s, as well as many of his contemporaries such as Kid Ory and Jelly Roll Morton, represent some of the only examples of what Early Jazz may have sounded like prior to 1917 in New Orleans. Because recordings don’t go back any further, all we can do is speculate based on those who originally came from the city and how they approached making music in the following decades, as well as drawing from the earlier influences in the 19th century and any personal accounts that still exist. As such, in my prior resource on Early Jazz, the characteristics explored in the latter part of the entry also can be used to describe the hot music of Chicago in the Jazz Age. To avoid doubling up on information, the main takeaways can be found below. If you want to explore the sound further feel free to check out my earlier resource which goes into considerably more detail.

A front line horn section of a minimum of 3 horns (cornet, clarinet, trombone)

Typically the cornet would take the melody while the clarinet played an obligato above and the trombone would play a counterline below

Each of the horns were allowed to embellish the melody

The rhythm section was made up of a banjo, tuba, and drums, with piano being added along the way

Almost all of the music featured a heavy two feel at a moderate to fast tempo

Stop time sections and breaks were very common

The repertoire primarily drew from blues, ragtime, marches, and popular songs of the day

However, there’s plenty more to talk about when it comes to Chicago jazz that I haven’t unpacked yet, specifically when it comes to Louis Armstrong. So instead of focusing on the various sounds of the ensemble and how to recreate them, the rest of this section is going to look at another aspect of hot jazz: improvisation.

As Early Jazz transitioned into the Jazz Age, the approach to improvisation changed. Initially, a jazz solo referred to embellishing the melody, however somewhere in the early 1920s musicians began actually creating unique lines when soloing. If you’ve done any reading on the topic, you’ll find one name comes up more than any other as being solely responsible for the shift, the great Louis Armstrong. As I wasn’t there back in the 1920s, I can not say whether Armstrong was the first person to establish the new format of jazz soloing, with that said, it is unquestionable that his approach to improvisation greatly influenced the entirety of jazz music.

The idea of creating a unique solo likely came from the influence of the clarinet part which always improvised an obligato in Early Jazz. Drawing from arpeggios and guide tone resolutions, the clarinet would try to slot their lines among the other two horns. Having grown up hearing this approach, it is quite possible that Armstrong experimented with playing clarinet lines on his cornet and over time they merged with his melodic embellishments. Without speculating further, regardless of what led to the shift to improvisation, Louis Armstrong mastered the new approach and quickly established himself as one of the greatest jazz musicians of all time.

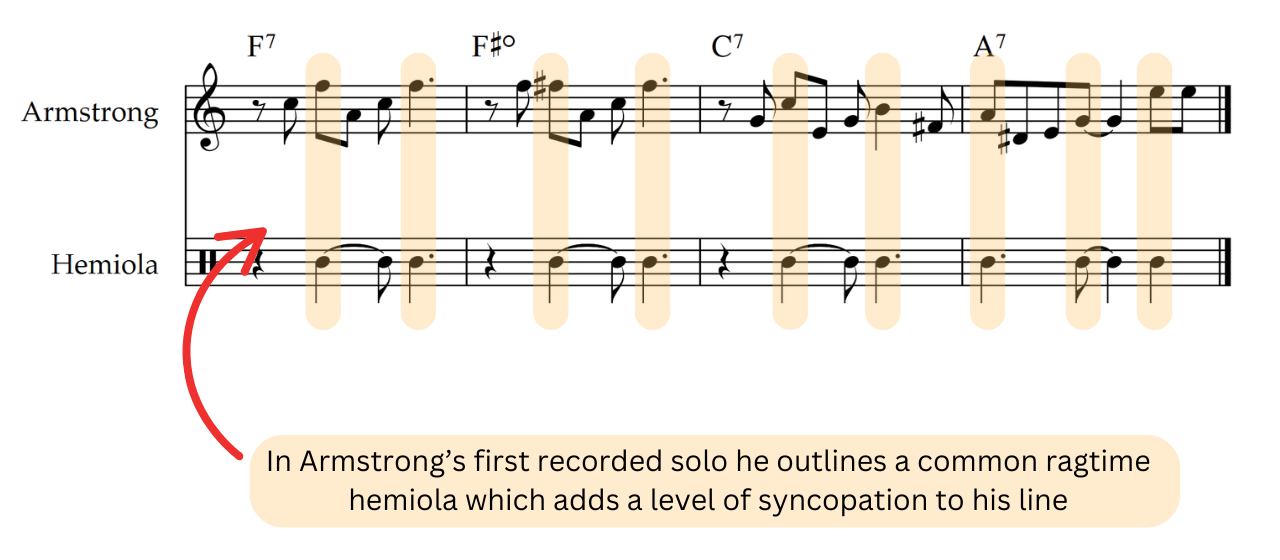

It was during his time in King Oliver’s band that Armstrong was first recorded improvising. One of the earliest examples is Chimes Blues recorded in 1923 which clearly marks a departure from the common approach at the time. Not only does he play an original solo, but Armstrong also has a more defined approach to swing than when the ensemble is playing. One aspect that may have helped amplify his interpretation of swing is the fact that the solo is built around a common ragtime hemiola. By framing the majority of the solo around the rhythm, Armstrong was able to incorporate syncopation into each phrase.

Chimes Blues

Solo by Louis Armstrong

Looking at the notes, for the most part each phrase is built on arpeggios from the accompanying harmony, however the arc of the solo follows guide tone resolutions which help connect each bar with one another. For the most part, these guide tone lines create the melodic foundation of the entire solo and when Armstrong chooses to not embellish them with arpeggiation, he often uses a mixture of chromatic approach tones to resolve a phrase. Looking slightly deeper, it is interesting to see that in some bars he highlights color tones outside of fundamental notes of the chord progression. While it may be difficult to say exactly when jazz harmony started to take on extensions and alterations, it is clear that at the start of jazz improvisation, highlighting notes such as the 9th and 13th were part of the tradition.

Chimes Blues

Solo by Louis Armstrong

Looking at the notes and rhythm of Armstrong’s solo on Chime Blues are important but there are also other components to the performance which are harder to analyze through music theory. For example, his tone has a level of confidence that helps convey each musical phrase and his approach to articulations and vibrato marked a change from typical conventions. All of these individual components came together to help give Armstrong a distinctly individual sound, one which created a new dynamic in jazz. Instead of focusing on the collective, Armstrong offered an alternative, one which focused on the individual and showcased their ability in a standalone manner.

Whole books have been dedicated to Armstrong’s influence, carefully analyzing many of his great solos from the 1920s and early 30s. However, many of the traits found in his solo on Chimes Blues ring true throughout the decade and only become far more established as the years go on. Only four years after the recording of Chimes Blues, Armstrong recorded his solo on Potato Head Blues, and released arguably his most famous recording of the era the next year, West End Blues. Although there had only been a few years separating these events, in that time Armstrong had come a long way and developed rapidly. By comparing his solo on Chimes Blues with Potato Head Blues, we can see how far his approach truly had progressed. All of the foundations were still there, but the nuance and creativity of the latter far exceeded the former.

One of the key qualities of Armstrong’s approach to improvising was his desire to experiment. Due to a high number of performances and recording dates in the 1920s, he was able to push his limit consistently and find new solo devices to add to his arsenal. Whether it be new rhythmic approaches, differences in phrasing, or extending the upper range of the trumpet, Armstrong had a go at everything. Regardless of how successful his attempts were, he never compromised on a few major traits, namely having a strong sense of rhythm, a forward propulsion in his phrasing, a commanding tone, and above all, a fantastic sense of swing. These four characteristics alone were infectious to the musicians who surrounded Armstrong and by the end of the decade many were trying to emulate his approach.

It is clear that these pillars of Armstrong’s style existed with King Oliver’s band in the early 20s, so much so that his wife Lil Hardin (also the pianist in the band at the time) suggested he leave Oliver to pursue a solo career under his own name. So in 1924 he did just that and accepted an invitation to play as a featured soloist with Fletcher Henderson and his band in New York City. Unbeknownst to both Henderson and Armstrong at the time, this multi year stint on the east coast would change the direction of jazz, blending the variation of jazz developing Harlem with Armstrong’s individualistic style of playing. Thanks to the collaborative efforts of Armstrong, Henderson, and chief arranger Don Redman, the dynamic of jazz started to shift away from the ensemble and onto individual soloists, with arrangements separating improvisation from ensemble passages. That’s not to say this wasn’t already being done earlier, however it is in these years that a new model was established which broke away from the collective improvisation style found in the New Orleans/Chicago sound. But we’ll get to that a little later when we explore New York in more detail.

Armstrong didn’t stay in Henderson’s band for too long, leaving after 14 months of employment to return to Chicago. There are many possible reasons behind this but one of the strongest was to pave his own way as a recording artist outside of an established ensemble. Upon returning to Chicago, he formed his Hot Five band and expanded them two years later to the Hot Seven. It is from this ensemble we get his famous solos on Potato Head Blues and West End Blues as well as numerous other iconic Armstrong recordings. Collectively the recordings from this one ensemble, albeit with many personnel changes, launched Armstrong from not just a favorite among musicians but into a new pedigree of popularity, becoming arguably the first American pop star.

It is at this point we have to depart from Armstrong as his career starts to move beyond the scope of the Jazz Age. In order to provide some closure though, most of his major innovations came from this period and afterward he chose to reap the rewards of his hard work more so than to continue experimenting musically. While some see this as unfortunate, and many at the time calling him a sell out for primarily playing/recording Broadway hits out of Tin Pan Alley, I think many of us would also follow the same path if we were put in the same situation. Regardless, Armstrong provided a new model for jazz and consistently refined it over the 1920s. His influence on this period of jazz was monumental, with some of his many contributions including: popularizing the individual approach to jazz soloing, establishing a model for phrasing and capturing the swing feel, almost singlehandedly providing the standard of how to build a jazz solo, shifting horn playing to a more legato approach, and extending the trumpet range within the jazz idiom. That’s not to mention his fabulous vocal work too, where he helped create a new style of singing which mimicked his approach to playing, paving the way for future jazz vocalists such as Ella Fitzgerald, as well as popularizing scat singing. While there were many other highly inventive musicians based in Chicago, no one else had quite the same impact that Armstrong did on jazz and American music in general. However, as we mentioned earlier, there were more innovations worthy of mention than just Armstrong’s and to cover them we have to shift locations.

New York

Similar to South Chicago, Harlem was one of the largest communities of black Americans in the 1920s. For many residents, the neighborhood located in uptown Manhattan represented a new style of life where black culture was celebrated. A drastic contrast to many other areas in the United States at the time. Often this particular period in history is called the Harlem Renaissance, and marks the first time in American history where black people were able to pursue life in a somewhat similar way to white Americans. Of course racism was still abundant in the United States and all it took was for a black person to travel a few blocks south to be reminded of that harsh reality, but compared to the lynchings of the southern states, Harlem provided the foundation for many black Americans to escape poverty and for some to thrive in society.

In relation to music, one of the first major developments that took place in Harlem was the creation of stride piano. Thanks to the growing black middle class, a new generation of young musicians were growing up learning how to play piano. While the repertoire they learned was primarily Western classical music and not Early Jazz, this actually provided a technical base which informed their approach to playing regardless of the genre. As such, when the young musicians began to start playing other styles of music, they had a distinct sound that differed to other jazz musicians around the country who had not received the same musical upbringing, focusing more on the clean interpretation from classical music versus the heavy blues influence of the Midwest and South.

One of the most notable pianists from this period was James P. Johnson, who very much established the status quo for Harlem stride piano. As ragtime was one of the most popular piano styles at the turn of the century, musicians such as Johnson would have primarily played ragtime at house parties and gigs in order to make a living. However, instead of interpreting ragtime through the a highly vertical, bar to bar manner as was established by marches in the late 19th century, Johnson added more momentum to the left hand which gave a certain horizontal drive to the music. It is uncertain exactly why Johnson interpreted the music in such a manner, perhaps it was the influence of the blues or any number of other factors, but what we do know is that the new approach was popular.

Due to the more technically proficient musical abilities of the new generation, ragtime was pushed in other directions too. While the left hand part of ragtime does feature large leaps between bass notes on beats 1 and 3, and chords on 2 and 4, the Harlem pianists took this a step further and made the leaps stretch even further. They bumped up the tempos, and embraced more athletic feats in their right hand, almost trying to cram as many notes as possible within a single bar. The development of stride also came at the same time as the swing feel was emerging, giving the style a rhythmic lilt that is mainly absent from ragtime. However, it is known that pianists such as Jelly Roll Morton, as well as other established ragtime pianists in the early years of the 20th century, would take considerable rhythmic liberties compared to the written sheet music, so there was already a foundation in which the swing feel was being applied. All of these factors came together to create an almost virtuosic new approach to piano which became the norm in Harlem. A great example of early stride piano is Johnson’s Harlem Strut.

Moving on from stride, one name which has to be mentioned when discussing the music scene in Harlem is James Reese Europe. At a time before the majority of America had heard the sounds of Early Jazz, Europe opened the Clef Club in 1910, an organization that helped support black musicians as well as housed a 125 piece orchestra, the first all-black orchestra in American history. The ensemble primarily performed syncopated, ragtime influenced music, and helped pave the way for jazz to take a hold of Harlem in the coming years. There’s a lot that can be said about Europe, but in the context of this resource his name is worthy of mention as he laid the musical foundation for many of the artists we are about to discuss. He had a staggering life and really was an early champion of black musicians, not only helping those locally but also introducing international audiences to African American music. Unfortunately his life came to an abrupt end after being stabbed by a fellow band member in 1919, dying at the age of 39. To pay respect to the amazing work he did, here is a recording of the 369th US Infantry “Hell Fighters” band which he led.

In the following decade, two more bandleaders would emerge out of New York’s scene, drastically changing the world of jazz forever. They were Duke Ellington and Fletcher Henderson. Both grew up outside of New York but found their way there in the 1920s and ended up carving out significant careers in music. While Ellington was able to emerge from the Jazz Age and secure decades of work for himself and his band, Henderson on the other hand didn’t fare so well. However, Henderson, alongside multiple arrangers for his band, arguably did more to establish the big band arranging tradition that took the jazz world by storm than Ellington. The story behind each of them is fascinating, and understanding each of their music is vital to recreating the sound of the Jazz Age.

Henderson

Growing up in Georgia as the son of a middle class family, Fletcher Henderson enjoyed a different upbringing than the generations of black Americans before him. Although he learned classical piano from a young age, he initially chose to study chemistry with aspirations to earn a master’s degree in science at Columbia University. While working in a laboratory, Henderson found work as a musician on the side and quickly realized that music offered more opportunities than the scientific field due to the racism which existed at the time. Almost coincidentally, Henderson was able to line up multiple jobs as a musician and established himself as the musical director for Black Swan Records between 1921 and 1923, where he accompanied blues singers during the blues craze. During this same period he also ran his own ensemble, though primarily as a recording band for various record dates.

For his own band, he picked up a young reed player by the name of Don Redman in 1923, who also signed on as the chief arranger for the ensemble. To begin with, Redman primarily took stock charts and altered them for the band. Fortunately, there exist recordings from 1923 of some of these arrangements which give us a great insight into both how the band sounded as well as Redman’s early arranging style. One such example is Dicty Blues.

There’s a lot we can dissect from the recording, with the first characteristic being that there are more instruments in the ensemble compared to those from the Early Jazz period. Specifically, there are more saxophones, with Henderson employing three different reed players at the time. Supposedly Henderson had been influenced by the four person sax section of the California Ramblers, a popular white dance orchestra, and so expanded his own saxophone section to try and capture the same sound. By incorporating multiple saxophones, Redman was tasked with adapting the standard Early Jazz formula where a single clarinet would play an obligato above the ensemble. From the recording we can hear that Redman decided to maintain the obligato in one of the reed parts while adding an additional background riff part in the tenor sax. Interestingly, something which was quite common at the time was to have a bass saxophone within a reed section instead of having a tuba, an orchestration technique that really only existed in the late 1910s and 1920s due to the limits of recording technology. We can hear that Redman assigned the third reed to the bass sax and stayed within tradition by assigning it to the bass line. Outside of the reed section, the remaining instruments all took on the traditional roles established in Early Jazz.

Dicty Blues

Arranged by Don Redman

Shifting gears from instrumentation to form and development, Redman stays mainly within the scope of Early Jazz for this arrangement. Most of the melody sections feature the standard collective improvisation, with the only unique quality being a background tenor sax riff feature. For the various interludes and outro he mainly makes use of full band figures with the horns primarily playing homophonically. However, in the intro Redman breaks the tenor sax from the rest of the horns, establishing a unique sax line that contrasts to the hits in the rest of the band . Another point of interest comes in the first two solo sections where a small number of horns are utilized on repetitive background figures behind the solos. While this is not a far stretch from other Early Jazz examples, it is a technique which breaks from the common stop time or collective improvisation textures that commonly occurred behind a solo.

Dicty Blues

Arranged by Don Redman

Lastly, the recording demonstrates a considerably different approach to the swing feel compared to the Chicago/New Orleans based bands. When listening to recordings of the same year by King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, you hear a more loping triplet based swing with a large amount of legato, however Henderson’s band plays far more strictly with more of a dotted eighth/quaver and sixteenth/semiquaver approach. When compared side by side, the New York sound is more rigid which makes sense based on the development of the scene. Due to their distance from the blues traditions of the South and their prominent background in classical music, many New York bands were not able to capture the same feeling that the bands from New Orleans and Chicago were able to achieve. One notable aspect of the growing black middle class was the desire to detach themselves from any remnants of slave culture. Musically, this meant pushing away the association with the blues. As a result, while the new generation of musically trained black Americans were technically proficient on their instruments, they lacked the same feeling when playing jazz present in their colleagues who had grown up in the South, at least initially.

Before moving on, it is worth noting that Henderson’s band recorded another take of Dicty Blues a few months later but this time added a second cornet to the lineup. Most of the arrangement is quite similar with the main differences coming from Redman utilizing the second cornet as a supportive harmony voice underneath the lead.

In 1924 Henderson was offered the house band position at Club Alabama, which gave him the opportunity to turn the band into a full time ensemble. Although the recordings give the impression that the group was similar to an Early Jazz ensemble, in reality Henderson’s band was very much one of the many dance bands in New York at the time and played a wide range of repertoire. It was common for such dance bands to perform classical waltzes, ragtime numbers, and many other popular styles. Unfortunately this depth of repertoire was never captured in the recordings of the era. Like all dance bands, with the emergence of Early Jazz in the late 1910s, the new hot jazz trend was just another cog in their wheel. Due to popularity of the style, these were the tracks that were recorded in the 20s in the hopes to generate better sales.

Not long after becoming a full time band, Henderson was offered the opportunity to perform at the Roseland Ballroom which then led to a string of engagements at the venue and established Henderson’s ensemble as one of the greatest bands in New York. In the second half of 1924, Louis Armstrong accepted an invitation to join the band, adding a third cornet to the ranks and bringing the total number of horns to eight as Henderson had also started to include a tuba too. Without knowing it, Henderson had initiated a shift in the New York sound with the addition of Armstrong. Although Henderson’s band was made up of fantastic musicians, the ability to play hot jazz authentically had not quite made it to New York. However, Armstrong brought a direct connection to the source material of Early Jazz which transformed the entire approach of the ensemble, albeit taking many years to achieve. One of the most noticeable examples of this is the transformation of Coleman Hawkins’ sound before and after the influence of Armstrong, yet it is still clearly evident in the rest of the members of the band too. All you have to do is look to the recording of The Stampede in 1926 to hear the difference.

Unfortunately, Armstrong’s stay in the Henderson band only lasted 14 months but it was enough to establish a cultural shift in the New York sound. During that time, as well as for a couple of years afterward, Redman continued writing for the band and developed many new arranging concepts for the ever growing ensemble. Now with three reeds and four brass, Redman decided to split each instrument group into sections, establishing the foundation for big band orchestration for years to come. It’s unclear exactly when this approach started to take shape in the ensemble but a wonderful demonstration of the technique can be heard on The Henderson Stomp recorded in 1926.

The Henderson Stomp

Arranged by Don Redman

Another innovation by Redman was the use of block chords to harmonize each horn section. It may seem commonplace today, but in the 1920s there were no established jazz voicing rules and this was the first time that jazz arrangers had dealt with voicing such large horn sections. Block chord harmonization also went against the traditional view of contrapuntal harmonization established in 18th century counterpoint as it relied on heavy parallel movement within the inner voices. Interestingly, this approach was also used by Ellington in his early compositions. Redman had recorded with Ellington in 1926 so the two were at least familiar with one another but exactly who had the idea first, we will never know. However, the use of block chords most likely stemmed from piano voicings. Perhaps the writers liked the sound or it may have been more practical in order to churn out new arrangements quick enough to meet performance demands, either way they became the go-to harmonization technique for large ensemble jazz.

The Henderson Stomp

Arranged by Don Redman

Across his four year employment in the Henderson band, Redman used a wide range of instrumental textures. In the brass it was common for the straight mute to be used, most likely due to the influence of King Oliver. He also favored using the reeds as a clarinet trio in three part harmony, a technique that likely stemmed from the influence of stock arrangements of perhaps the Paul Whiteman orchestra.

With more horns also came the ability to experiment with orchestration through form and development. Notably, Redman used many varied textures for melody sections, taking full advantage of the opportunities available to him. It was common for him to not only employ the full ensemble, but also at times just the reeds or brass and sometimes just a single instrument to play the melody. While the history of the instrumental jazz soli doesn’t have a definitive start point, it is likely that by highlighting either the reeds or brass in harmony on the melody, Redman established the foundation for such developments to take place in later arrangements.

Stampede

Arranged by Don Redman

Building on the horn background technique he had displayed with Dicty Blues, in later arrangements Redman fully developed the concept and featured various combinations of backgrounds behind soloists. Two of the most common devices he used were harmonized pads and repetitive riffs.

Stampede

Arranged by Don Redman

Eventually, Redman too would leave the Henderson band, departing in 1927 to join the McKinney Cotton Pickers. In his absence Henderson decided to take up the responsibility of arranging for the band, building off of many of the techniques that Redman had originally developed. Somewhere in the latter half of the 20s, the band expanded once more, picking up a second trombone and fourth reed. It should also be noted that somewhere in the early years of the band the cornets shifted to trumpet with the cornet typically only being used for hot solos ala Armstrong. However, this too would change to all trumpets by the end of the decade.

One area that is often overlooked when it comes to the Jazz Age is the type of harmony that was being used by arrangers. While improvisation mainly followed in the footsteps of Armstrong for the decade, arrangements started pushing the harmonic boundaries established by Early Jazz. As the horn section grew larger, voicings left the world of triads to start capturing more chord tones and diatonic extensions began being incorporated as the norm. Although I am unsure of exactly when this change took place, it was very much established by the second half of the 20s and can be seen in Henderson’s composition D Natural Blues recorded in 1928.

D Natural Blues

Fletcher Henderson

Interestingly, even though diatonic extensions were being used, the harmony very rarely included chromatic alterations. Instead, in order to create tension it seems that arrangers would make use of a few common devices such as diminished chords, dom7#5 chords (most likely from the relation to the melodic minor or the whole tone scale), and chromatic approach chords, alongside the already established blue note tradition. In particular, chromatic approach chords led to some results which mimic the tritone substitution method made popular in the coming decades, potentially suggesting that at least some jazz musicians were aware of the technique two decades prior to the emergence of bebop. As with a lot of music in this era, there was a high dosage of modal interchange, most likely due to the popularity of the sound with the songs produced by Tin Pan Alley, as well as the bVI. It should also be mentioned that American music went through a slight obsession with the whole tone sound in the 20s, and bands such as Henderson’s made full use of the trope too. Passing chords expanded from the diatonic and diminished options popular in Early Jazz to also include chromatic planing, most likely as a way to deal with the chromatic approach tones often found in melody lines. Ultimately, the combination of these techniques created a much denser harmonic landscape which provided a new level of complexity in jazz.

D Natural Blues

Fletcher Henderson

Stampede

Arranged by Don Redman

D Natural Blues

Fletcher Henderson

To clarify, it is likely that these sounds had existed to some capacity elsewhere at the time and were probably on display with Early Jazz pianists such as Jelly Roll Morton or Harlem stride pioneers like James P. Johnson, however it was in the Jazz Age where they were utilized in large ensemble jazz for the first time. Based on the level of improvisation present in the 20s, an argument could be made that perhaps only pianists and arrangers were aware of the harmonic shifts taking place. Most soloists stuck to highlighting fundamental chord tones and guide tone lines with the emphasis primarily being on other elements of performing such as rhythmic placement rather than the specific notes being played. However, as we live a century on from the Jazz Age it is impossible to know for sure exactly how aware, or maybe more accurately, how much the musicians actually cared about the harmonic developments taking place.

Interestingly, when looking at the handwritten manuscripts of Henderson we get a better idea of the expectations on each of the instruments. For example, the piano was always notated mainly following the typical ragtime tradition from Early Jazz where the bass notes are in the left hand with chords on two and four. However, at times there would be specific chord voicings written followed by slashes to indicate repeating said voicing. Surprisingly, there is no sign of chord symbols on the piano part at all, indicating that it was the norm for pianists to read voicings and if they did venture away from the sheet music, they had to work out themselves what chord symbol was being created by the voicings written. In contrast, the banjo part almost always had slashes with simplified chord changes. Where the piano may have a D6 voiced out, the banjo was given the chord symbol D.

As the bass role was still played by a tuba, all bass lines were written out with no chord symbols given. Often the bass line would actually imply inversions to the chord symbols written in the banjo part and at times would prioritize the shape of the bass line over actually landing on a root note or fundamental chord tone. These lines were also doubled in the left hand of the piano giving the impression that the bass lines were likely fixed for each arrangement with little to no room for embellishment. Finally, drum notation was extremely simple, mainly featuring slashes or multirests with the text “swing” or “fake” for the duration of the section. Any time a certain rhythm was notated it would be written on the snare and bass drum, however it is unclear whether the drummers would interpret this precisely or use it as an indication of what rhythms to play across the kit.

Before looking at the later years of the Henderson band, we first need to explore the other developments of the 1920s as many of them had a strong influence on the post-Redman sound of the ensemble. As mentioned earlier, there was another titan in the New York band scene, someone who made a significant mark on jazz and American music in general and also began his career in the Jazz Age, none other than the formidable Duke Ellington.

Ellington

Before diving into the significance and contributions of Ellington it may be wise to outline the scope of this particular resource as his career extended over five decades and encompassed many developments. In this section, I will be specifically exploring the start of Ellington’s career and the music he developed in the 1920s and early 30s. I will save a deep dive into later iterations of his band and compositions for another resource as they land outside of the Jazz Age.

Similar to Henderson, Edward Kennedy Ellington grew up outside of New York, albeit slightly closer, in a middle class family in Washington D.C. Unlike Henderson though, Ellington decided to dedicate his life to the pursuit of music at a young age when he fell in love hearing ragtime. Around the same time he also picked up his trademark nickname “Duke” from his school friends as a commentary on how he presented himself. As a teenager, Ellington showcased an entrepreneurial spirit and booked his own performances as well as began writing music, beginning with Soda Fountain Rag in as a 15 year old. By the age of 18 he had officially formed his first ensemble. “The Duke's Serenaders,” which received early success playing formal engagements for both black and white audiences in D.C. When his drummer, Sonny Greer, received an invitation to join a New York based band, Ellington decided to move to Harlem as well, but after multiple months of trying to make it in the highly competitive scene returned to D.C. Years later in 1923, Ellington’s band ended up being offered an engagement at a club in Harlem, which ultimately saw them relocate once again, however this time more successfully.

After a few personnel and leadership changes, Ellington became the bandleader once again, now of a six piece ensemble named “The Washingtonians.” The band recorded a few times in 1924, however it wasn’t until Ellington partnered with manager and publisher Irving Mills in 1926 that his recording career took off. Most of the sides from this particular part of Ellington’s life reflect the popular styles of the day with no major innovations. That all changed though, when Mills was able to secure a contract for the band to play at the Cotton Club in 1927.

The primary role of the Cotton Club house band was to back multiple different revues which featured a mixture of dance numbers, comedy sketches, as well as a wide range of other variety style acts. There was a high rotation of music needed, resulting in Ellington contributing new compositions and arrangements regularly each month. As part of the contract requirements, the band also had to expand to an 11-piece ensemble, thrusting Ellington into a position to explore new approaches to writing music for the band.

The first major breakthrough came from a collaboration with trumpeter Bubber Miley, resulting in the creation of Ellington’s “jungle sound.” Note that this name was created as a marketing strategy by the white ownership of the Cotton Club and leaned heavily on racial ideology that black American music was exotic and associated with far away places such as the African jungles. In reality, that was far from the truth, as we unpacked in the previous resource on Early Jazz, but due to the success the term had in attracting audiences to the venue, the early music of Ellington is still often associated with the name.

Miley had been heavily influenced by the mute work of King Oliver, and developed his own approach to playing with the household plunger, combining other techniques such as growling to emulate the sound of a human voice. At the time it was a revolutionary way to play the trumpet and offered a completely different approach to the popular Armstrong sound. Miley also taught trombonist Charlie Irvis how to create the sound too, and eventually Joe “Tricky Sam” Nanton when he replaced Irvis in the band. Not only was Miley a creative performer, he also contributed a number of compositions to the band such as Creole Love Call, East St. Louis Toodle-Oo, and Black and Tan Fantasy. It is unclear exactly how much of these compositions were aided, if at all, by Ellington, but what we do know is that these three compositions ushered a new wave of popularity on the Ellington band.

For the most part, the “jungle sound” was defined by two, or perhaps three major characteristics. The first was the mute work by Miley and Nanton, which created an incomparable timbre to any other jazz music of the day. In many of the famous recordings, this specific texture was paired with a minor chord progression, often orchestrated out in low reeds (either clarinet or sax). There are other examples though, such as in the beginning of Black and Tan Fantasy, where instead of low reeds underneath a solo trumpet or trombone the melody was harmonized on muted brass in straight mutes. Finally, a potential third characteristic would be the use of three clarinets in the upper register in harmony, a signature technique by Ellington in this period. However, this was utilized on other compositions which fall out of the “jungle” category and wasn’t necessary for a piece to capture the sound. The high clarinet trio was also not unique to Ellington and we have actually already seen it being utilized by Redman in the same time period.

East St. Louis Toodle-Oo

Bubber Miley & Duke Ellington

Although the “jungle sound” title did come from a racist origin, Ellington used the term to his advantage, allowing himself to experiment maybe more drastically than other jazz composers at the time as anything he did could be justified as being “exotic” and permissible. Looking at later examples such as the intro to Jungle Blues from 1930, you can see that Ellington incorporated considerably more dissonant voicings compared to those used by Henderson at the time.

Other than those particular characteristics, most “jungle sound” pieces included a mixture of other more straight ahead components. Ellington was always experimenting so every piece was slightly different but many of the compositions did make use of sections similar to those we have looked at in the Henderson band. However, Ellington was a genius when it came to developing an arrangement, making each solo section feel like an integral part of the overall piece, a skill that wasn’t always executed to the same degree by Redman and other arrangers of the time. The main difference was that while Ellington’s compositions were still stooped in Early Jazz tradition, they marked an evolution from the sound, taking the best elements and incorporating them alongside new techniques and textures. Whereas most other writers of the time more directly tried to emulate the hot jazz sound.

The Ellington band also had other styles in their library, including another unique category considered “mood” pieces that interestingly have a lot of similarity with the popular sweet jazz of coming years. They featured lush harmonies with full orchestrations and leaned more heavily into complex chord progressions. Due to the slower tempos, the full color of the chords were able to speak, allowing the individual melody lines to float above the ensemble. The specific harmony in question was a mixture of modal interchange, secondary key centers, and the all important dom7#5 chord, which in this case was definitely derived from the popular whole tone scale at the time even though Ellington rarely paired it with a whole tone based melody line. One of the best examples of this category of Ellington compositions is Mood Indigo recorded in 1930.

Mood Indigo

Duke Ellington

Alongside the “mood” and “jungle” repertoire, there was one other major category of music that was recorded by Ellington during the Jazz Age: hot jazz. Compositions such as Double Check Stomp, Cotton Club Stomp, Stevedore Stomp, and Wall Street Wail are all fantastic examples of Ellington’s take on the popular style of the 20s. Notably, one such piece released in 1927, Washington Wobble, may have the first walking bass line in jazz history. It is hard to say as various bands were experimenting with a four feel in the bass in the second half of the 20s, however this particular track is one of the earliest recorded examples. When the bass initially started to hint at a four feel, the most common option was to simply repeat the root note of each chord and not to actually have a continuous melodic line. However, you can clearly hear in Washington Wobble that the bass line has a certain arc and sounds like what we would call a walking bass line today. While having the walking line be present this early in Ellington’s band is significant, it was actually another bassist who championed the new approach and made it the norm across the country. But you’ll have to wait until we get to Kansas City for that.

The energy exuded by the Ellington band in these hot jazz numbers is quite something. Although we are now in a different century to when these were made, you can clearly hear the excitement in the music and clearly representative of the dance culture that existed in Harlem at the time. Many of the techniques used by Ellington followed in a similar vein to those already established by Henderson and Redman, but with his own spin on the style. It’s a shame that these recordings don’t get as much attention these days compared to the “mood” and “jungle” numbers, however it makes sense as they are not nearly as ground breaking compositionally in comparison to tracks such as Mood Indigo or East St. Louis Toddle-Oo.

It would be a titanic undertaking to go through the entire catalog of Ellington’s band from this era and note every technique he experimented with as there are so many. As Ellington was primarily self taught in the area of composition, everything was on the table and the residency at the Cotton Club allowed him to trial new ideas every night if he so pleased. Whether it be different combinations of instrumental textures, harmonic ideas, or voicings, almost all pieces from this era demonstrate some kind of experimentation, and those that Ellington liked were incorporated in later compositions. With the luxury of hindsight, we can now see that the years at the Cotton Club were pivotal for Ellington’s creativity, and out of the residency he was able to create a collection of techniques and sounds that he could use countless times for the rest of his life.

Professionally, the Cotton Club also came with a life changing opportunity in the form of weekly live broadcasts to the rest of the country. Just this alone ended up making Ellington a known bandleader across America, allowing him and the band to tour extensively and sell more recordings. It is from this foundation that the band was able to make enough money through the depression and continue existing for many more decades. One final point before moving on, coming out of the Cotton Club period, Ellington chose to always compose in his own way, never falling to temptation and following the popular trends of the day. Interestingly, it is because of this exact reason that Ellington is so highly regarded today while so many other large ensemble composers from the first half of the 20th century have been forgotten. At the time he received a lot of negative feedback from the press by sticking to his own way of writing, causing major debuts such as Black, Brown and Beige to be considered a failure by multiple publications. Yet ultimately Ellington had the last laugh because those works, in a similar way as what happened with the Rite of Spring and Stravinsky, are now considered some of the most creative and critically acclaimed in the Ellington library.

Our journey with the New York scene is not quite over but we have to make a detour to the Midwest before continuing. To a city with a deep musical history and one which created another unique approach to jazz that differed to what we have seen in both Chicago and New York. It was the birthplace of countless jazz musicians over the decades and helped usher in an irresistible beat which influenced every band which heard it. I’m of course talking about Kansas City, Missouri.

Kansas City

To understand the development of the Midwestern approach, we need to take a step back and look at how exactly the black music scene in places such as Kansas City got started. The story of Kansas City actually follows a similar trajectory to that of New Orleans, so much so that there is an argument that jazz actually started in the Midwest and not in Louisiana. Like many urban centers around the country, freed slaves made their way to cities such as Kansas City after the civil war and developed a localized variation of the blues. While the residents didn’t create an equivalent to the Second Line tradition, they did still bring many of the same musical characteristics to the area. Local black American artists such as Scott Joplin also ran smaller ensembles with quite similar instrumentations to that of New Orleans bandleaders like Buddy Bolden. We will never know if the Midwest actually birthed Early Jazz, but it was a prominent musical hub which had many of the same ingredients as New Orleans.

With the rise in popularity of ragtime at the end of the 19th century, the Midwest fell in love with the style, potentially more so than elsewhere in the country. One reason why could be because there is a claim that the origin of the style actually came from somewhere in St. Louis, Missouri. Regardless, the local music scene was dominated by the style well after the rest of the country had moved on. It wasn’t until the blues craze of the 20s that ragtime was finally replaced as the popular music, with local bands featuring prominently blues based music. As mentioned earlier, blues was always present in the Midwest for many decades prior to the 1920s, the main difference with the blues craze was that the music was elevated in the minds of the public and found its way into the dance halls.

Like every major hub around the United States in the 1920s, Kansas City was home to many dance bands looking to make a buck, however it was also common for these bands to visit surrounding states such as Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Texas. As a result, most dance bands were known as territory bands. One such band was led by Bennie Moten, who started off as a small fish in the local scene but gradually clawed their way up the pecking order over the decade. From his early recordings, it is clear that Moten was trying to emulate the Chicago/New Orleans sound of King Oliver as can be heard on Crawdad Blues recorded in 1923. Similar to the comparison between the 1923 Henderson recordings and King Oliver that we did earlier, when listening to Moten’s approach against King Oliver you can hear a drastically different type of swing feel. Well actually there is no swing feel and Moten’s band plays all of the eighth notes/quavers straight.

Even though Moten may have started with an absence of swing, his band did demonstrate something quite unique in their early recordings. In Elephant’s Wobble, released in the same year, the final chorus features a four feel in the whole rhythm section, a remarkable difference to the status quo this early in the 20s.

In the following years, similar to the trajectory of both Ellington and Henderson, Moten’s band developed its own variation of hot jazz. Due to the prominence of the blues in the Midwest, the band started incorporating considerably more riffs in their recordings compared to those located in Chicago or New York. Unlike what we have seen with the Henderson and Ellington ensembles, Moten was likely not the mastermind behind all of the compositional decisions in his band. It was the norm at the time for riffs to be made up on the spot by horn members and those that made it into recordings were likely the favored lines by the band. A prime example of these types of riffs can be heard in 18th Street Strut released in 1925.

18th Street Strut

Bennie Moten

Like all dance bands in the 20s, Moten’s band expanded multiple times over the course of the decade, first starting off as a typical six piece ensemble with three front line horns and a three piece rhythm section. By 1925 an additional cornet, reed, and tuba were included, and in the following year added another two reed players. It’s not exactly certain who wrote for the ensemble as it became apparent in later years that some charts credited to Moten were actually written by arrangers in the band. Many musicians also have the belief that many of the pieces were learnt by ear but with the developing sophistication evident from the recordings, it is hard to believe that there was no arranger behind the scenes penning the charts. Unfortunately we may never know who was behind the shift in the Moten band’s sound, but what is evident from the recordings is that in the space of 1923-27, the band’s sound followed a similar pattern to Henderson. Like everyone, they were influenced by Armstrong’s approach and then started incorporating many of the arranging techniques they heard from the Henderson band that were pioneered by Don Redman.

Another prominent territory band worth mentioning is Walter Page’s Blue Devils. Founded in 1925 by Page, the band actually operated out of Oklahoma City. Like many territory bands, the Blue Devils didn’t have the same access to the recording studio as bands in Chicago or New York due to the lack of record labels based locally. As a result, there are only a couple of recordings of the band from 1929 but both demonstrate a fantastic insight into the Midwestern approach. They also feature a name you may have heard of before on the piano, William “Count” Basie.

Both Squabblin’ and Blue Devil Blues feature a similar approach, prominently featuring individual soloists with the ensemble playing various riff choruses. Sometimes these would be pads and other times the Charleston rhythm. Notably, Walter Page on bass established a driving four feel at the end of both pieces, something we saw earlier with Moten’s Elephant’s Wobble. As Ellington had released Washington Wobble two years earlier, there is very much the chance that Page had been influenced by either Moten or Ellington too, however it was what came next that established Page as the first great walking bassist.

One other aspect that can be heard on both recordings is the use of the hi-hat, something that wasn’t as noticeable, or potentially didn’t exist yet, in the recordings of Henderson and Ellington. Unlike the cymbal that we know today, the original hi-hat was only played by the foot and had no cymbal stand. As a result it was known as the sock cymbal. In the late 1920s and early 30s, the cymbal began being elevated through the use of a stand and stayed there ever since. However, it wasn’t until a few years later where it became the main time keeping device on the drums. Interestingly, in the Blue Devils’ recordings, you can hear it being used on both the back beat as well as articulating certain band figures and fills.

In the Midwest, competition between territory bands was rife, with cutting contests constantly taking place to establish who was the better band. Everyone knew that the best bands got the better gigs and had a higher chance of lining up recording dates. Most likely in fear of losing his position in the local hierarchy, Moten took on a bold strategy of hiring members of competing bands so that he would always stay on top. Eventually this practice saw many members of the Blue Devils join Moten’s band, first with Basie, an interesting choice as Moten also played piano. One by one Page’s band was dismantled until eventually all of the prominent players were hired by Moten. Some of the acquisitions included vocalist Jimmy Rushing, arranger Eddie Durham, saxophonist Lester Young, and even Walter Page himself on bass.

Notably for this resource, the addition of arranger Eddie Durham to Moten’s band helped transform their sound further. With the Blue Devils being absorbed into the band, the music developed to have even more ensemble riff sections, a more consistent four feel, and picked up various aspects of the Redman arranging style through Durham. Supposedly in 1931, Moten’s band was on the brink of collapse, so while on a tour that brought them to the east coast, Moten purchased a couple dozen charts from the Henderson band and had both Durham and a newly acquired arranger, Eddie Barfield, adapt them. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly what charts were added to Moten’s library, but looking at the recording releases around that time one possible arrangement was Milenberg Joys. Whether it was part of the acquisition or not, we may never know, however a comparison between Henderson’s recording and Moten’s does provide a fantastic insight into the differing approaches both bands took.

The Henderson recording in 1931 follows very much in the style we discussed earlier with nothing too distinct standing out. I will mention that the use of the hi-hat, primarily on the back beat, is considerably more present and the improvised solos have continuously improved since the early 1923 recording of Dicty Blues. On the other hand, Moten’s band offers a completely different interpretation with their 1932 recording. The contrast can be heard almost immediately as the first chorus features a solo trumpet against a sax background before launching into a driving four feel. The difference between the walking upright bass compared to the slower two feel tuba in Henderson’s recording is night and day. The Moten version also mixes ensemble melody passages with a considerable amount of riffs giving a whole different personality to the piece.

Somehow the band managed to stay together, most likely due to the popularity of their 1932 recordings which happened to take all of the characteristics discussed thus far and combine them together into a new refined sound. From an arranging standpoint, most of Moten’s sound was quite similar to Henderson except for two major factors: a driving four feel in the upright bass and an oversaturation of blues based riffs. The piano also seemed to be put front and center, very much putting a spotlight on the stride piano style of Basie. These characteristics alone transformed the approach to jazz and brought a whole new wave of excitement to the music. Like most musical developments, at the time the new sound didn’t have a name, but in the coming decades it started to be called the jump style. These days most people simply refer to it as the Kansas City approach but personally I think jump helps differentiate the style. Some wonderful examples of the Moten band from 1932 include Moten Swing, Toby, and Prince of Wales.

While the Moten band was likely not the only band to play jump music in the Midwest, they definitely became the most popular and were likely the group which led to the style being spread outside of the region. Even to this day, you can tell how much excitement was created just by shifting the bass part to a continuous walking line instead of a two feel. In order for this development to take place, it was essential for the tuba to be replaced by the upright bass. The lighter sound and the ability to play continuous notes without needing to take a breath created a sense of buoyancy that simply was unobtainable by the tuba.

One final characteristic of the Midwestern sound that unfortunately was not captured prominently on recordings at the time is the concept of trading fours. It was quite common just before the final melody chorus for soloists to trade four bar improvisations with one another. By doing so, it helped build an upward arc of excitement at the end of a solo section which perfectly led into the energetic conclusion of an arrangement. Most likely due to the capabilities of recording technology paired with the opinions of producers and record executives, most of Moten’s tracks only feature individual soloists and I’m not aware of any that have any trading fours. Fortunately, due to the abundance of musicians which came from Kansas City in the period, we know that trading fours was common and in fact the norm for most live performances.

Over the coming years the band kept expanding and eventually landed on three trumpets, two trombones, four saxes, and a rhythm section made up of guitar, piano, upright bass, and drums by 1934. Tragically, in 1935 Moten passed away with the leadership of the band being passed down to Basie. If you’re a fan of big band jazz then you probably know what happens next but if not, it is from the remnants of Moten’s group that the Old Testament Count Basie band was formed. But that’s a discussion for a different resource as it takes us out of the Jazz Age.

When Cities Collide

We’ve made it! Hopefully you now feel somewhat more comfortable with the differences and similarities between the three major approaches to jazz that existed in the 1920s. But before I wrap up this resource there is one final important point that needs to be addressed. Each of the different sounds we’ve looked at didn’t just stay locked to a certain area, in fact all of them ended up coming together and influencing each other. We already explored the first case of this occurring when Louis Armstrong moved to New York to join Henderson’s band in 1924 resulting in the Chicago/New Orleans approach mixing with the local variation of jazz. However, it wasn’t until the early 30s when the Kansas City approach came across and made an impact in New York. Interestingly enough, one of the major points where the two variations met was once again in the Henderson band.

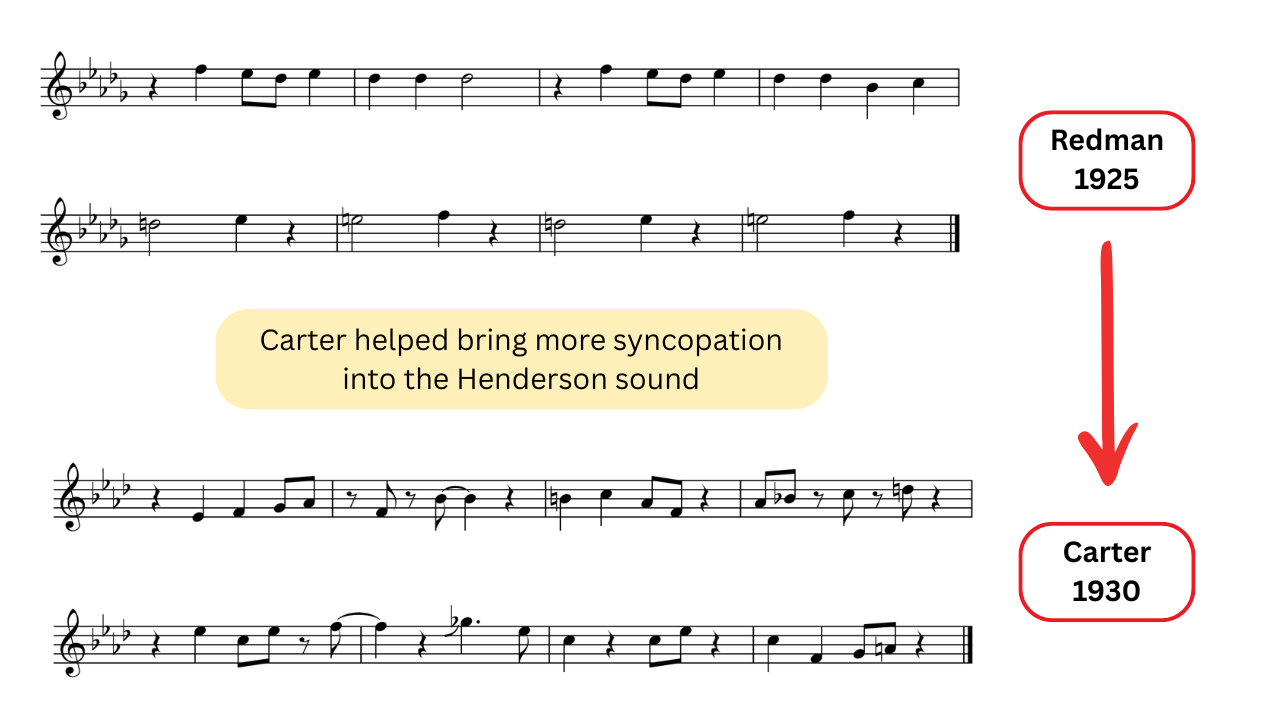

Picking up where we left off, Henderson ended up replacing Redman with a young Benny Carter in 1928, an up-and-coming alto player who also dabbled at arranging. Similar to Redman, Carter helped progress the sound of the band further, sharing the writing duties with Henderson and Henderson’s brother Horace. Notably during the period between 1928 to 1931, a few more significant changes took place within the band. Arguably the most significant was the change from tuba to upright bass and from banjo to guitar, providing a much lighter texture in the rhythm section. Both of which were likely inspired by the developing sound of jazz in Kansas City which was starting to catch on in New York.

Between the three writers of the band, a new formula for large ensemble jazz emerged, paving the way for the next era of jazz. Just as it had done in Moten’s band, with the lighter feel of the upright bass, bass lines began transitioning from a two feel to a four feel resulting in a new pulse in the music. It was also around this time that the high hat transitioned from a floor mounted cymbal into what we know today. By raising the cymbals, drummers now had the opportunity to play them with sticks and not just their feet. As a result, drummers such as “Papa” Jo Jones, known later for his work with Count Basie’s band, started experimenting with shifting the pulse from the bass drum to the cymbal. Within a few years this became the standard for playing time on the instrument and added a completely new feel to the music.

As the time feel in the rhythm section changed, Carter took full advantage and started experimenting with the syncopation in the horn sections. By having such an established drive in the bass, it freed up the horns to not have to play as many downbeats and as a result the horns were able to swing harder. If you listen to one of Carter’s first contributions to the band, Somebody Loves Me, you only have to listen to the first melody chorus to see just how much bounce the music has compared to earlier recordings such as T.N.T. or D Natural Blues.

On top of the four feel, the Henderson band also took the other major influence of jump music, the heavy use of riffs, specifically riffs that could be played continuously over a blues progression regardless of the chord changes. This time it was Horace Henderson who incorporated the technique in his arrangement of Hot and Anxious in 1931. It doesn’t take long before you hear a riff which sounds like it could have come straight out of the Moten band. However one particular riff in the piece overshadows all of the rest as it is arguably one of the most famous riffs and obviously inspired Glenn Miller’s In The Mood. Finally, Horace snuck in one more new approach at the end of the piece with a slow fade out.

And just like that the Kansas City approach had been incorporated into a New York band. By combining all of these elements together, Carter and Horace created a new model for the Henderson band. One which was built off of the early developments by Redman on the Chicago/New Orleans hot sound, the improvisation style of Armstrong, the driving four feel and riffs of Kansas City bands like Moten’s, the syncopation of Carter, the fade outs of Horace, and the ever expanding horn section. However it didn’t become an overnight success. Actually, during the Great Depression, Fletcher Henderson had to break up his band and sell a large portion of his repertoire in order to get by. It just so happened though that the person he sold his library to was none other than clarinetist Benny Goodman. Goodman not only purchased the charts but also employed Henderson as an arranger for his Let’s Dance radio show, saturating all of Goodman’s repertoire with the established Redman/Henderson/Carter approach. What happened next though redefined jazz, with Goodman’s success in 1935 ushering in the Swing Era. But that’s for another resource.

The Takeaway

The Jazz Age was an exciting time for jazz music with so many arrangers experimenting across the country. It paved the way for the sound of big band jazz in the Swing Era but was also filled with so many amazing recordings that deserve to be held up against any of the classics from later periods. In this resource I’ve only looked at a few artists but know that there were so many more bands and writers that were making a mark for themselves and establishing unique sounds. And a warning on things to come, there are even more artists and arrangers that emerge in the coming decade when big band jazz takes America by storm. However, this resource is long enough so you’ll have to read all about the Swing Era in the next resource.