The Techniques Which Defined

The Crooner Sound

One of the most popular categories of jazz history has to be the period between the mid 1940s through to the end of the 1950s where vocalists such as Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald reigned supreme. Although at the time many of these vocalists were simply considered to be pop stars and not necessarily related to jazz in the same way as others like Dizzy Gillespie or Miles Davis, the arrangements that backed them were often deeply influenced by jazz and represented a continuation of the great arrangers of the Swing Era. This was a time where the role of the big band in American popular culture was being questioned and the musical tastes of the western world were shifting. Fortunately, between the Swing Era and the introduction of Rock’n’Roll there was a brief window where the sound of large ensemble jazz dominated the airways, albeit as accompaniment for the popular singers of the time. To this day, much of the music from this brief window is still remembered fondly and for me personally, it’s some of my favorite music to listen to.

Sometime during high school a guest clinician, the great Melbourne based drummer Danny Farrugia, came in to work with the big band I was playing with. While I can't remember exactly what was said about the piece we were playing I do remember one thing, the recommendation that I should listen to the Sinatra at the Sands album. I had heard the name Frank Sinatra before and was familiar with Count Basie but had never really ventured out from the Atomic Basie album and had definitely never heard Sinatra sing before. That all changed though when I got home and immediately bought the Sands album on iTunes. With a lengthy road trip from Melbourne to Sydney on the horizon, I decided to wait until the car ride so that I could listen to the album front to back. And I’m so glad I did, because to this day I can still remember that moment as if it had occurred yesterday. It was early in the morning on a Saturday, some time around 4 or 5am when my mum and I got in the car. I loaded up my ipod and pressed play on Come Fly With Me, and as soon as the opening passage hit my ears I knew I was in for a treat. From that point onward I was a Sinatra fan for life.

Over time I had the opportunity to play many of Sinatra’s greatest hits with various bands and upon returning to Melbourne in 2017, I started up my own band with the intention of playing his music. As a result, many weeks were spent transcribing his albums, exploring the classics such as Songs For Swingin’ Lovers as well as listening to a wide range of arrangers from Quincy Jones to Nelson Riddle. Not only was it a joy to spend time sitting with the music, but to present it to live audiences and see the joy that the classic songs bring to so many people has been a wonderful experience over the last few years.

Throughout this entire process, from being introduced to the music of Sinatra as a teenager through to transcribing and playing many of his albums as an adult, it never really dawned on me what made the music of this period so special. Surprisingly, it actually didn’t cross my mind until early 2025 when I started looking deeper into big band arranging and how certain techniques developed across a number of decades. Prior to this moment though, I simply associated many of the techniques I had acquired over the years as being from the post-swing era period. Fortunately, by spending more time with the music of the 1920s and 30s, the special qualities of the big band arrangements that were created in the 1950s started to become much more obvious.

In this resource I’ve tried to compile those specific differences into a singular entry, building off of the techniques established in my other resources on the Jazz Age, the Swing Era, and bebop, by exploring the wonderful music of arrangers like Axel Stordahl and Nelson Riddle. This was a time of big bands being accompanied by strings, with vocals soaring over lush harmonies provided by mixed woodwind sections. However, it wasn’t always about the vocals and bands like those run by Count Basie provided a new model for swing music that has since gone on to become a staple in school bands across the world thanks to Sammy Nestico. Like always, to understand the music it is important to understand the context which created it, so I think it’s time to stop talking about me and go back to the early 1940s when a significant recording ban was wreaking havoc on the music industry.

Shifting Perceptions

The period between 1942 and 1944 was a pivotal time in jazz history where multiple factors ultimately resulted in the demise of the Swing Era and the start of the next wave of popular American music. As we discussed in the resource on hardbop, one of the influential moments of the time had to do with rationing during WWII. Due to having some level of dispensable income and nowhere to spend it, many white patrons would often go out to dance halls, causing an increase in demand for swing music which led to a rise in band wages. For white bands, interest in swing music was at an all time high but the dance hall was the only place you could hear a big band as there was a recording ban in place across the United States.

This particular ban was quite important when looking at the entirety of jazz history because two outcomes came from it. The first was that it took place at the critical moment when bebop was being developed. Due to the recording ban, there was a crucial gap in recorded history when jazz musicians were starting to experiment with new ideas. As a result, the first bebop recordings emerged after the ban at a time when many of the critical ideas had already been established.

The second outcome of the ban was the shift of popularity towards vocalists. During the first half of the Swing Era as well as the sweet music of the 20s and early 30s, the vocalist generally played a secondary role to the bands which they accompanied. But when the recording ban came into effect, the only musicians allowed to record new music were vocalists, resulting in two years of prime radio coverage being dedicated to acapella groups. While singers had been popular prior to the ban, such as Bing Crosby, instrumental music still was the main draw for audiences across the country. That all changed with the recording ban though, and over two years of being fed vocal based music, the appeal for dance bands shifted to their accompanying vocalists. Many of the main band leaders used this to their advantage and picked up vocal trios and quartets as well as changed their marketing to be built around the singers they employed.

The culmination of these factors led to the fracturing of the big band scene with the final nail in the coffin being administered by the end of rationing. The general public was now free to spend their money however they wished, diluting the revenue that had once gone directly to the venues and musicians. Unwilling to compromise on the high wages they had become accustomed to, big bands started to break up in favor of small groups. As we explored in the hardbop resource, one result of this situation was the emergence of rhythm and blues. However, another pathway presented itself through vocal driven music. Coming out of the recording ban, vocalists now captured a majority of the public's attention and were able to capitalize on the market by becoming headline artists. This particular shift resulted in the creation of the pop singer concept as we know it today.

In a matter of years, the music of the Swing Era was replaced by the first iteration of American pop music (now referred to as traditional pop), a new style which was dominated by the crooner. For the most part, the music drew heavily from its origins in the sweet music of the 20s and 30s, as well as the stereotypical tropes of swing music in the 40s. The result was a sound which had one foot in jazz and the other in classical, leading to a mixture of instrumentations being present on recordings. In the first half of the 40s, string sections had become all the rage for many major dance bands, often being formed as a tax write off for the leaders, such as with the Tommy Dorsey band. While the strings may not have been able to compete with the traditional big band in a live setting, they were prominently featured in recordings, paving the way for the new vocally inspired pop music to draw from in the late 40s and 50s. Arrangers such as Axel Stordahl were some of the first to develop the vocabulary of the new style, establishing a new musical foundation filled with oboes, flutes, bass clarinets, and full string sections for singers like Sinatra to stand on top of. The horns and rhythm section also were thrown into the mix, creating an elaborate mix of textures for writers to draw from.

As traditional pop developed, three major categories were created: Hollywood pop film scores, standalone big band instrumentals, and the repertoire which accompanied crooners. All three came from the same set of characteristics but each one had a different flare which made it distinctly unique. In the film world, writers like Henry Mancini created elaborate scores which drew heavily on the pop music of the time, borrowing jazz harmony and rhythms but applying them to full studio orchestras which drew heavily from the classical world. Whereas in the big band instrumental department, writers such as Sammy Nestico and Neal Hefti penned original compositions that blended elements of bebop with characteristics of dance band music in the 40s. And finally, in the crooner world, arrangers took the popular repertoire of both Hollywood and Broadway and reimagined the songs in a way which would often add elements of the previous two categories while also making sure that the vocalist was featured effectively throughout. There was definitely a lot happening! For this specific resource we will be focusing predominantly on the latter two categories by looking at a mix of arrangements from Sinatra’s library as well as a number from the many arrangers associated with the Basie band.

Textures & Orchestration

One of my favorite aspects of traditional pop might just be the beautiful colors that were able to be created by blending different textures together. Originating in the 1920s with the sweet music of the Paul Whiteman orchestra, combining classical instruments with jazz sensibilities had been well established by the time the Swing Era was coming to a close. However, what made the arrangements of the 40s different to prior decades was the use of jazz harmony, with arrangers now drawing on extensions and alterations within their voicings for both the strings and woodwinds. Of course the other noteworthy factor was the focus on the vocals throughout a piece, something which was not nearly as common in sweet music.

For most crooners, two contrasting types of arrangements had been established by the 40s, the ballads which drew more heavily from orchestral colors and light swing numbers which were somewhat of a watered down version of the swing instrumentals that filled the Swing Era and now focused on the vocalist delivering the melody instead of the horns. In both types of chart the melody was seen as king and it was essential that nothing got in the way of whoever was carrying it. As the vocalist almost always was assigned to the melody, all other instruments were now seen as secondary. Interestingly, by shifting the focus toward the vocalist it allowed arrangers to make more of a mark on a chart through the unique countermelodies they penned.

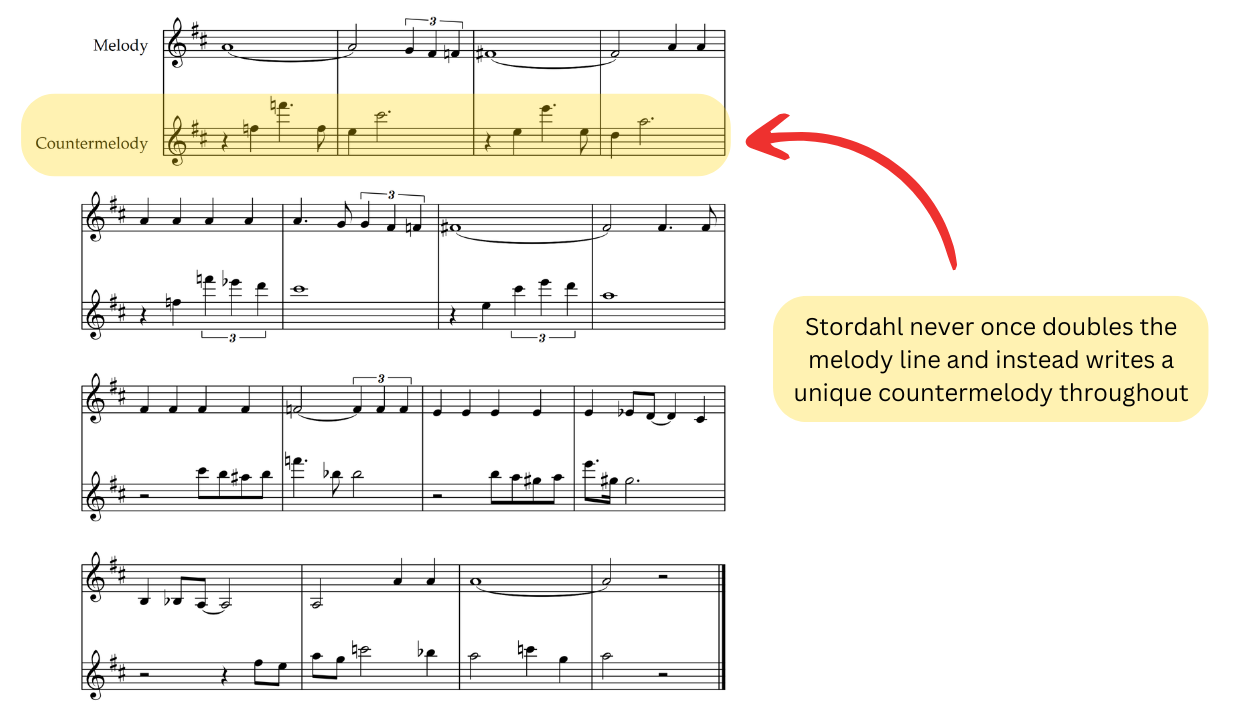

Thanks to the arranging book that Nelson Riddle wrote, we also know for certain that it was considered bad taste to double melody lines underneath a vocalist during this era. One of the main reasons was that it restricted the interpretation of the singer, forcing them to adhere to the rhythms that were written and not how they personally heard the melody being performed. As a result, a majority of the arrangements for vocalists such as Nat King Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, and Frank Sinatra left the melody completely untouched, allowing them the freedom to do with it as they wished. A fantastic example of this can be heard in the classic Night and Day as recorded by Sinatra with the Tommy Dorsey band in 1942. Not once during the entire piece does Axel Stordahl double the melody, instead using a fantastic countermelody throughout which helps provide a unique identity to the piece.

Night And Day

Arr. by Axel Stordahl

Taking a deeper look at the orchestration used in this time reveals a myriad of different instruments, all bringing a wide range of tonal characteristics to the music. In the ballads the common foundation of the ensemble was a five person woodwind section, a large string section boasting multiple violins, violas, and cellos, and a mixture of other unique voices such as french horn and a harp alongside a conventional big band brass and rhythm section. For the most part, the arrangements leaned heavily on the reeds and strings, with the rhythm section plodding along in the background. When the trumpets and trombones were used, they almost always were in some kind of mute in order to balance with the delicate sounds of the strings and woodwinds, with cups and hats being the most common. The result was an extremely colorful ensemble sound which blended the best of the big band tradition with many of the textures from the classical orchestra.

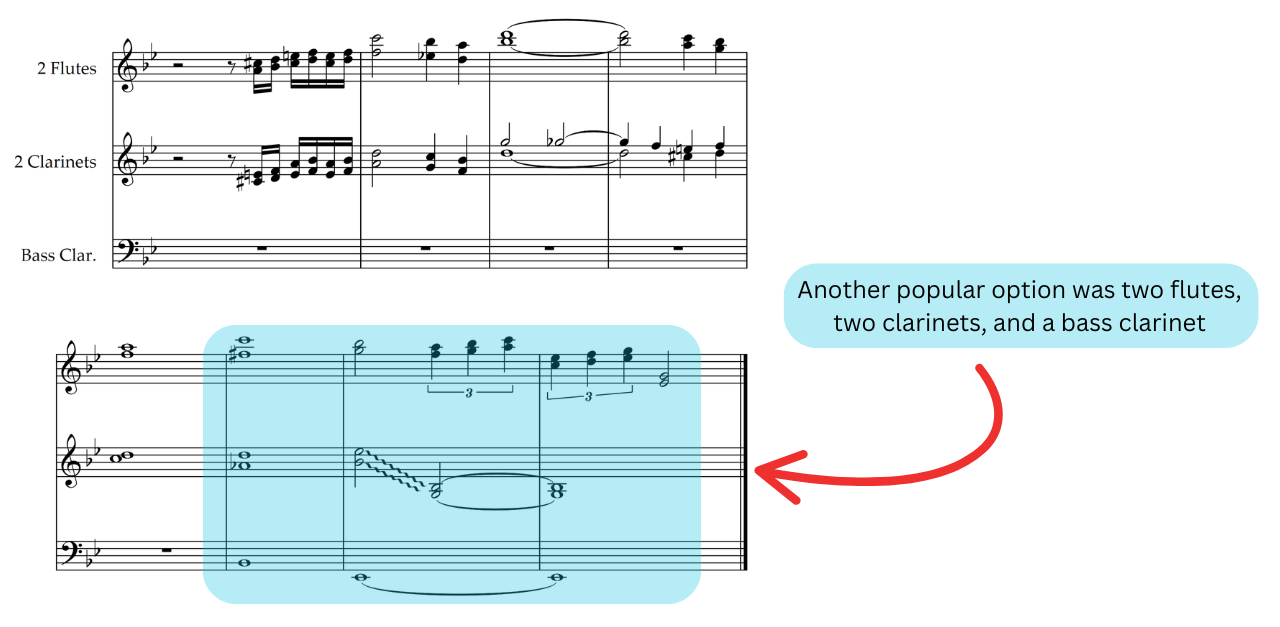

While every arrangement used a unique blend of voices, there were some common conventions that were leaned on. For example, it seems that the general approach to woodwinds was to use three or four clarinets and one or two bass clarinets for a total of five instruments. With this foundation, some voices would then double on flute, piccolo, alto flute, oboe, english horn, or bassoon for special moments while the rest would remain on clarinets. When these doubles did appear, they almost always would be used as a solo voice for a particular moment, sometimes by themselves and sometimes doubling other instruments such as the lead violin. However, there are also cases where flutes would be used alongside clarinets to create a full section sound too. This particular style of orchestration also extended to other instruments in the ensemble such as the french horn, which typically would be reserved for specific melodic moments more so than collectively with other sections.

Christmas Dreaming

Arr. by Axel Stordahl

Christmas Dreaming

Arr. by Axel Stordahl

No Orchids For My Lady

Arr. by Axel Stordahl

No Orchids For My Lady

Arr. by Axel Stordahl

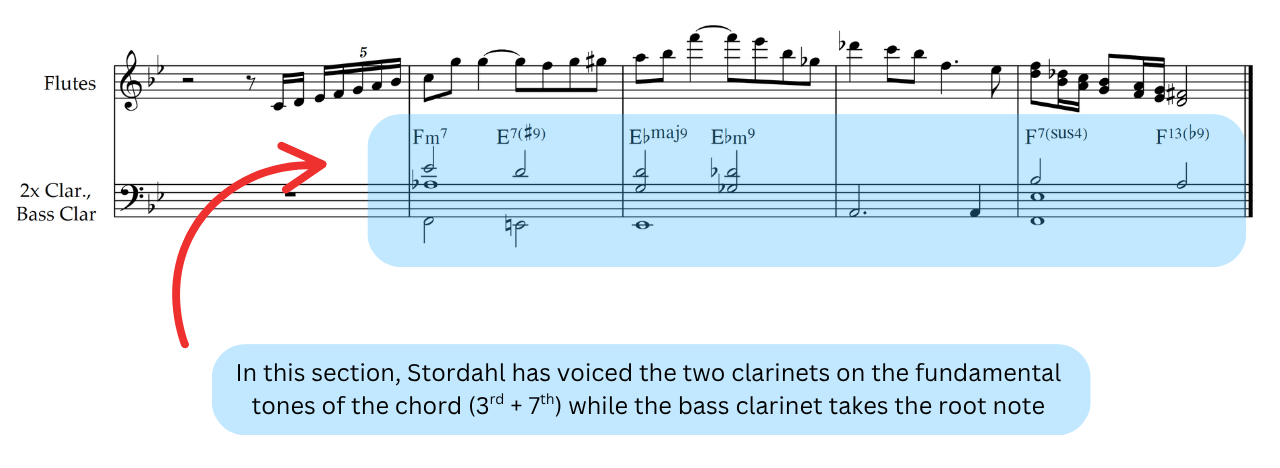

Due to the large amount of variety in woodwind doubles, the voicings that were used in the section could vary drastically from section to section. If the standard four clarinet and bass clarinet combo was used, almost always it followed conventional four note block voicings with the bass clarinet either being dealt with as a bass voice and being assigned the root note of the chord or as a fifth voice which would often double the top voice down an octave. However, it seems that even though the standard voicings would be initially laid out as some kind of closed position voicing, often they would vary from note to note in favor of inner resolutions such as in the manner of 18th century counterpoint.

I’ll Make Up For Ev’rything

Arr. by Axel Stordahl

When the situation became a little more complex with voices being assigned different doubles or being coupled with other countermelody lines, the voicings naturally changed. In most cases the remaining section would be broken into two or three part harmony which outlined the fundamental chord tones of the underlying chord progression. In other cases when the mixed instrumentation was voiced together there was a mixture of options depending on range. For example, with two flutes, an oboe, clarinet, and bass clarinet, the most common application was to treat the first four instruments as a group with the bass clarinet once again being broken off and treated like a bass note. The flutes would be the top two voices, the oboe the third, and the clarinet the fourth, with all four being voiced in either a four note closed shape or a drop 2. Like before, at times counterpoint rules would take priority and certain voices would resolve accordingly.

Christmas Dreaming

Arr. by Axel Stordahl

I’ll Make Up For Ev’rything

Arr. by Axel Stordahl

With so many different woodwind options to choose from, there were inevitably many other combinations and voicing options for arrangers to use. In Nelson Riddle’s book he mentioned a couple of others I haven’t come across in my score analysis journey yet, such as pairings between two flutes and clarinets with the flutes being voiced in two part harmony and then the clarinets doubling the notes down an octave. Some other combinations included the use of bassoon alongside two clarinets as well as his favorite grouping of 1-2 flutes, 1-2 oboes, 1-2 clarinets, and 1-2 bassoons being joined by three french horns which he made use of on Sinatra’s Only The Lonely album.

Moving over to the strings, it’s pretty safe to say that most of the countermelody work in the crooner ballads was carried by the violins. In almost every track I’ve listened to and analyzed, the strings provided the majority of the interest behind the vocals with only brief moments of other textures being sprinkled throughout an arrangement. It was also quite common for those other voices such as the flute or oboe to double the violin part but due to the mixing of the records, the violins often dominate the overall ensemble sound. Violin parts were often written over the entire range of the instrument, moving from the low register to the extreme upper register. Although the violas and cellos also enjoyed some level of melodic writing, they were constrained more often to pads underneath the moving violin parts. At times they would break free though, either playing a secondary counterline or having their own standalone part.

I’ll Make Up For Ev’rything

Arr. by Axel Stordahl

I Have But One Heart

Arr. by Earle Hagen

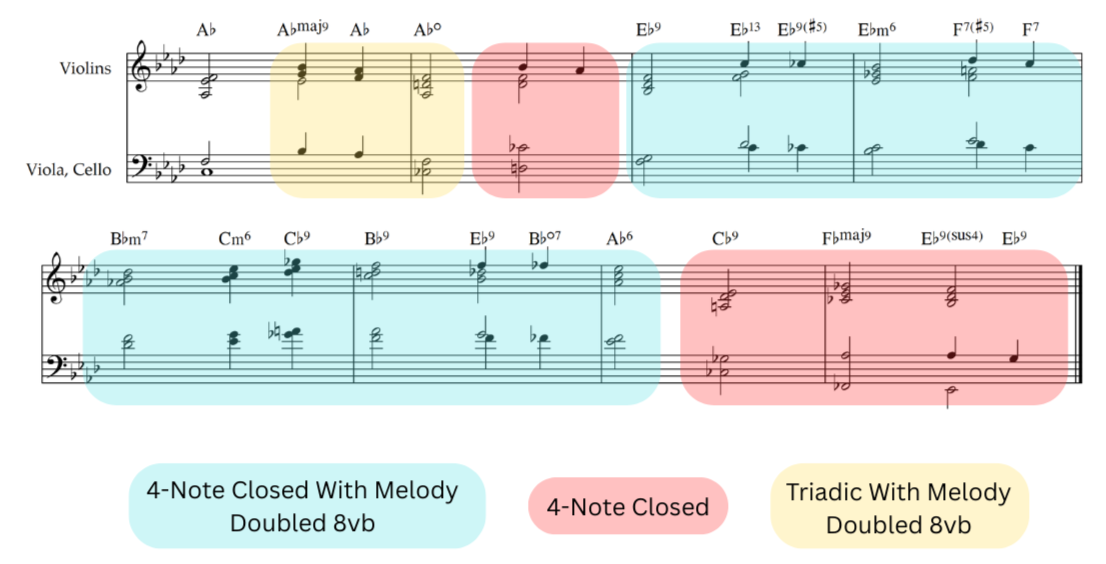

Unlike the smaller string sections which accompanied the dance bands of the early 40s, the studio orchestras were fitted out with considerably more musicians. As a result, the norm was to write three different violin parts often titled A, B, and C (also known as violin I, II, and III) alongside the violas and cellos, with divisi being common across all string instruments. Notably, the string bass was separated from the rest of the string section and generally maintained a similar role to other jazz styles by playing pizzicato bass lines. At times it could be used as an extension of the string section but for the most part it was considered a member of the rhythm section.

With so many instruments there were a number of different voicings available from tight closed shapes to wide open structures which covered multiple octaves. At times they would be rather simple harmonically and only outline the fundamental notes whereas other times they may cover a number of color tones too. Unfortunately, due to there being so many different options it’s quite hard for me to give you an accurate picture of every single type of voicing which was used. Instead, below you’ll find a few different examples which should hopefully give you a rough idea of how arrangers voiced the string section.

I’ll Make Up For Ev’rything

Arr. by Axel Stordahl

Just for Now

Arr. by Axel Stordahl

Nevertheless

Arr. by Axel Stordahl

Outside of the world of strings and woodwinds, there were many other instruments for arrangers to draw upon. Whether it be the trumpets and trombones, harp, or many different sorts of keyboard instruments, arrangers utilized them all. Fortunately for us, those three textures in particular were used in only one or two ways and are much simpler to understand compared to what we’ve just covered. In the world of the trombones, most often they would be used as a section of three or four and played long harmonized pads in block chords or simply outlining the fundamental harmony notes. Due to the tenor range of the instrument, they were the perfect sound to support the rest of the ensemble without getting in the way of other voices and were often used alongside both the strings and woodwinds to help fill out the sound of the group.

The Stars Will Remember

Arr. by Axel Stordahl

Harp parts were also relatively straight forward, with the instrument only having one function in the ensemble. At specific moments the harp would play a large flourish of ascending or descending notes, helping articulate a certain bar or build into a new section. These runs would often just be fast, multi octave arpeggios and act like the cherry on top of a beautiful moment. Sometimes, instead of the harp, the piano would play a similar sort of motif giving a slightly less transparent sound. However, it was also possible for the piano to be swapped out for other keyboard instruments like the celesta or harpsichord depending on the particular flavor of arrangement.

All The Things You Are

Arr. by Axel Stordahl

Hopefully by looking at these selections you are able to see just how expressive and filled with color the crooner ballads were. But as I mentioned earlier, alongside the ballads were the light swing numbers which had a different feel entirely. For the most part, these songs shed the diverse set of woodwinds in favor of the classic five person sax section, and the elaborate string parts were replaced with horn heavy counterlines. With that said, the strings didn’t leave entirely and generally were given long stretched out pads for the majority of a chart, sometimes escaping for a brief run or two. Generally speaking, there was not much difference between these types of arrangements and the instrumental swing numbers from the Swing Era. They both used the same type of vocabulary but with the crooners the horns were delegated to accompanying parts. There were some differences of course, namely with the form of an arrangement being shaped around the vocals, however most of the evolution when it came to big band swing numbers came from the instrumentals written by the likes of Sammy Nestico, Neal Hefti, Frank Foster and countless others.

Introductions, Shouts & Solis

As the Swing Era instrumentals were being replaced with vocal heavy songs, the space in which an arranger could put his mark on a chart also changed. Typically, without any vocals to contend with, an arranger could really do whatever they wanted at any time in order to showcase their artistic ability, such as change the melody or harmony drastically. However, with the melody now being assigned to the singer at almost all times, the creativity was channelled into countermelodies and small other sections. Quite quickly the introduction of a song became one of the best places for an arranger to leave their mark. As it preceded the melody, the first sounds penned were often completely original and set up many melodic ideas that could then be threaded throughout an entire arrangement. Even though it could be as small as four bars, a talented arranger could establish the entire mood for what was about to take place as well as put their stamp on even the most famous of songs in the introduction.

One such example was I’ve Got You Under My Skin arranged by Nelson Riddle in 1956 for Sinatra’s Songs For Swingin’ Lovers. In the first few bars Riddle used a wonderful bass clarinet ostinato alongside a set of syncopated hits in the celesta which is then echoed throughout the entire arrangement and assigned to a few different instrumental textures. Even more amazing is that this particular chart, which has now become one of the most well known Sinatra hits, was actually written in less than a day alongside two other tracks for the album. Famously, Riddle received news the evening before the final day of recording that he had to complete three more arrangements for the album. After what must have been a pretty adrenaline fuelled evening, he finished the final touches to I’ve Got You Under My Skin in the back seat of the car while his wife drove him to the studio. To make the story that little bit better, after the orchestra read the chart down, they immediately burst out in applause for Riddle as they recognized just how good the arrangement was.

I’ve Got You Under My Skin

Arr. by Nelson Riddle

Looking closer at the arrangement we also find something a little different to the big band songs written in prior decades. There is what we would now call a shout section right in the middle of the piece, splitting the vocals into two distinct sections of the song. In the Swing Era, shouts were primarily riff based sections that came at the end of a piece, but somewhere in the 1940s they started to be reworked into what we see in I’ve Got You Under My Skin. Most likely when the vocals began taking center stage, band interludes were implemented to break up the multiple verses being sung. These eventually evolved to a point where they would restate the melody, often molding the notes and harmony to create more impact and swing, with the brass being voiced in the upper register to add excitement. Over time this style of band interlude eventually became the norm instead of the ending riff based shout and was often incorporated into instrumental charts too.

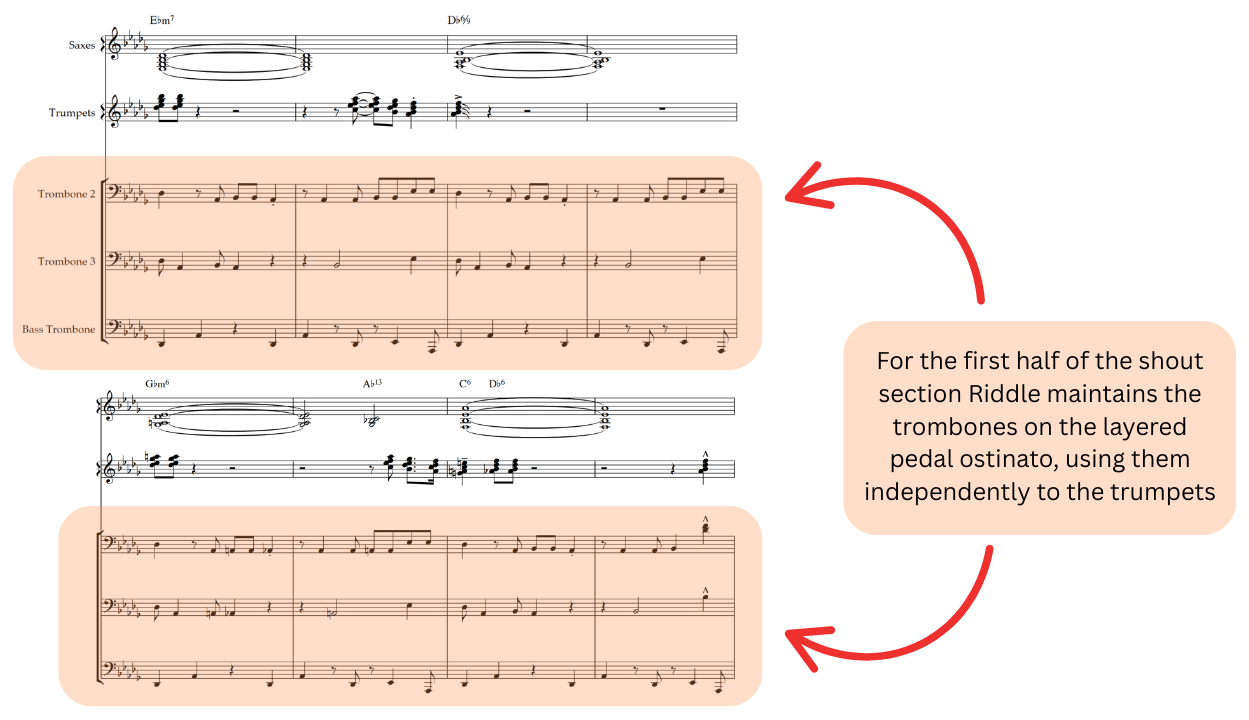

Taking a closer look at the shout section of I’ve Got You Under My Skin, there are a few notable takeaways worth mentioning. First of all, unlike Swing Era charts, the trombones have moments where they move independently to the trumpets, outlining an ostinato while all of the action takes place above them. Although this particular chart doesn’t utilize them as freely as others from the same period, such as Frank Foster’s arrangement of In A Mellow Tone, they are still independent for a full section.

I’ve Got You Under My Skin

Arr. by Nelson Riddle

In A Mellow Tone

Arr. by Frank Foster

It is also clear that the rhythm of the melody has been modified to swing harder and reinforce a greater level of syncopation. Due to the nature of the melody only featuring a few notes every two bars, Riddle initially filled the space with an improvised trombone solo, but later on brings the whole horn section together when the melody is more busy. At that moment the drums have some room to fill and set up horn parts. Similarly to what we just saw with the independence in the trombone section, this particular example only gives a small insight into what drum interjections could sound like, whereas other examples from the same period such as Neal Hefti’s Splanky give more room for the drums to play with.

I’ve Got You Under My Skin

Arr. by Nelson Riddle

Splanky

Neal Hefti

Alongside introductions and shouts, one other section became quite popular in the big band instrumentals of the 1950s and 60s: the soli. Most likely originating from the melody sections that were assigned to the reeds in the early big band music of Fletcher Henderson and similar bands, the soli came into its own after the Swing Era. Instead of restating the melody, arrangers used the section as a place to compose their own lines and tried to emulate the excitement of an improvised solo, albeit harmonized and with a full section. With the creation of bebop, solis were primed to take on a high level of harmonic, rhythmic, and melodic syncopation, which resulted in standout moments in arrangements that highlighted the virtuosity of the band playing them.

One of the most noteworthy was the saxophone soli on In A Mellow Tone arranged by Frank Foster in 1959. Foster didn’t hold back and used the saxes to their full potential, immaculately crafting rapid passages of semiquavers/sixteenth notes alongside bold melodic statements. The section executed the soli perfectly and threw in even more personality to make the lines feel as if they had been improvised. Like many sax solis of the day, this particular one mainly used block voicings with the bari doubling the melody down the octave. There are times where this shape is broken momentarily in order for more color to be included within a voicing, however the large majority of the soli utilizes the same voicing structure. The real strength of the section though, comes from the lead line which is a masterclass in how to write a great melody.

As we have just seen, many of the elements found in the light swing numbers for the crooners were also shared with the instrumentals played by the remaining big bands. There was a large crossover in ideas, most likely due to the arrangers often being booked for both situations. One notable difference between the two though was the emphasis on improvisation. In the vocal arrangements there would usually be eight or so bars at most of improvisation, if at all, whereas in the instrumentals there could be whole sections dedicated to a solo. This was likely due to the demands of record labels and the different audiences each type of arrangement was being marketed to.

Like the Swing Era that came before, eventually traditional pop would be pushed aside by new music. Thanks to the success of rhythm and blues, record labels copied the sound with white musicians such as Elvis Presley, fracturing the interest in Sinatra and other crooners. However the final blow came with the British invasion in the 1960s, where bands like The Beatles reigned supreme. As a result, the sound of traditional pop was relegated to the background, although it never quite faded completely thanks to avenues such as the Las Vegas casinos as well as the ever popular Christmas themed songs like White Christmas and Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas.

The Takeaway

There is no doubt that in the traditional pop era of big band writing, arrangers were able to take the established norms of the Swing Era and push them into even more interesting places. Whether it be incorporating new textures or redefining the form of an arrangement, big band charts went up a step in complexity. The only way forward from this point was to leave diatonicism and start incorporating more modern techniques. However, before touching on that there is one area which needs to be mentioned. Specifically, how musicians such as Mario Bauza helped integrate latin rhythms into the big band scene.