How Bebop Redefined

Jazz Vocabulary Forever

If there is one area of jazz that has defined the artform more than anything else it is bebop. No matter where you look you’ll find influences of the style today, stretching from music education all the way to modern jazz musicians. Somehow, even though we keep getting further away from the 1940s, the vocabulary of bebop has still lingered on in jazz. Whether you like it or not, it has become somewhat inescapable and if you choose to pursue jazz as a career you will inevitably come in contact at some point. But what is the point in learning bebop in the 21st century and what makes the style so important to jazz?

For years I didn’t know the answer to that particular question and pushed myself through a lot of unnecessary frustration to get to where I am today. Unfortunately, the institutions designed to explore the beauty of bebop often come with a layer of judgement due to focusing on execution rather than understanding. As such, they can push aspiring musicians away from learning, and for me I was given a double dosage through both high school and university which took years to move past.

My journey started back in grade 10. I had just been accepted into the senior big band and due to being a member of the rhythm section it was mandatory for me to attend weekly improvisation sessions alongside a few notable horn players in the band. No one had mentioned these extracurricular classes ahead of time, and when introduced to the fact that I had to be there I started feeling extremely nervous. I barely knew how to play my instrument let alone read chords and solo, and it probably didn’t help that the person who ran the sessions was the band director who had a habit of singling people out and yelling at them (such as when he chewed me out for 15 minutes at the first rehearsal for playing a note out of tune).

After a full week of stressing about the first Friday morning session, the day had arrived and I walked into the rehearsal room prepared for the worst. To my surprise nothing really happened. I was told to run some arpeggios from a chord progression and then was given almost no indication of how to use that skill to solo. Don’t get me wrong, my heart was still pumping every time it was my turn to try and improvise, but pretty quickly I realized that the sessions were put on primarily to help give the soloists in the band more time to learn how to solo over the repertoire. I still had to solo every now and then, but my place as the bassist never really extended to more than playing an accompanying role.

For three years I attended those Friday morning classes never knowing more about improvising than simply running arpeggios. Along the way I was recommended to listen to some of the greats like Charlie Parker but with no further information given. After trying to get through a few tracks it was clear that the music didn’t really resonate with me and when paired with the quality of the improv classes, I never was inspired to go away and learn more about soloing. Instead, I spent all of my hours trying to slap bass like Marcus Miller which seemed far more enjoyable than whatever my band director was trying to teach me at the time. Since then I’ve been able to see just how amazing it can be when a dedicated student is inspired by the right teacher, but unfortunately the director I had never found the right way to connect with me and so I spent those years exploring other avenues of music.

After finishing up my time in high school I soon found myself pursuing jazz at the tertiary level which meant more improvisation classes. My first year in the program was amazing. I was being bombarded with so much knowledge and I felt like a kid in a candy store but that slowly changed in my second year when I was confronted with the dreaded improv II class. The curriculum was purely built around bebop but instead of exploring anything about the style the reality of each class was running technical exercises the professor had written. Like my previous experience in high school, I had no clue how the content I was being taught actually related to improvisation and when I asked one day for more explanation, the professor screamed at me in front of the entire class. It’s safe to say that I felt pretty terrible and after that point I never really wanted to commit any more time to learn anything about bebop.

Jumping to the lockdowns of 2020, I had just begun running online courses as a way of scraping together some sort of income during the global pandemic. After a few months hosting individual sessions on jazz related topics, one of the students suggested I put together a course covering bebop and mentioned that many of their peers would also be interested in attending. Faced with an impending deadline to pay $30,000 thanks to the impacts of the COVID lockdowns, I put my disdain for bebop aside with the realization that running a course on the topic may be a wise financial decision. I threw myself at the situation and started reading about the many musicians associated with the style. To my surprise, I actually began to respect the music and the sizable impact it had.

Up until that point my only interactions with bebop had been in poorly taught improvisation classes which focused far more on theory than understanding the music itself. By taking the time to actually connect the dots and see the developments that artists such as Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker made, something clicked within me and I started to see the value in learning the style. As a result, I finally understood why in high school I was forced to learn so many arpeggios and in college had to play so many technical exercises. It all started to click and as an added extra also provided some level of therapeutic relief after so many terrible interactions with bebop in the past.

Coming out of such a turbulent period, I now have the utmost respect for the musicians which created bebop all those years ago and finally understand the amazing developments they provided to jazz. While Parker may still not be my favorite artist, I do see the significance of his legacy and have found enjoyment in the music created by many of his colleagues, especially Dizzy Gillespie. My hope is that this resource will provide a different experience than the one I lived through, unpacking all of the necessary avenues of bebop so that you can walk away not only understanding the theory behind each technique discussed but also the logic which led to its creation. As with the other resources on this site, everything on this page comes from an arranging perspective and is designed to help others emulate the sound of bebop in their own writing, however many of the topics discussed can also be directly applied to improvisation too. So sit back, get a snack, and buckle in because there’s a lot to cover!

The Birth Of Bebop

Unlike the styles which came before, bebop actually overlapped considerably with the Swing Era and developed simultaneously for a number of years. There was no official start to the style but based on the recordings that exist, the foundations were likely established sometime in the late 1930s. To begin with, the developments were small, mainly coming from a place of harmonic expansion where musicians experimented with making jazz more chromatic. As discussed in my previous resource on the Swing Era, there was a lot of color which existed in large ensemble arrangements, namely coming from the use of chromatic approach chords, whole tone derived sounds, and the use of diatonic extensions. However, these sounds were generally limited to the voicings used in the horn section and were seldom translated to the improvised solos at the time.

In order to access chromaticism, the two main methods for improvisers were to use blue notes (m3, b5, m7) or chromatic approach tones/passing notes. Both were played in a horizontal, melodic capacity and were rarely thought of in a vertical manner in association with a given chord symbol. In other words, improvisation prioritized creating lines which sounded melodic and were related to the key of a given piece, and any time chromaticism was used it was a by-product of this process more so than a calculated decision to outline a chord symbol or extension. However, as established in the clarinet obligatos in Early Jazz and in the first solos by Louis Armstrong, chord tone resolution was very much a key part to the improvisation process, demonstrating that jazz musicians were crafting solos with certain resolution points between chords right from the beginning of the art form. So it would be unwise to think that all musicians were unaware of how their chromatic notes related to a given progression.

Chromaticism itself was always in the air in the 1930s, with musicians such as Duke Ellington and Art Tatum constantly pushing the limits in their music by adding alterations into their chords. But it wasn’t until the latter part of the 1930s when those harmonic explorations began to be captured by a larger sphere of artists. In the world of improvisation, this first took place by expanding the available chromatic notes available, adding the b9 and b6 to the already established m3, b5, and m7 blue notes. To do this, a number of new techniques were developed which justified the notes such as side-stepping, tritone substitution, and implying extra chord resolutions outside of the written harmony. While these techniques were likely explored by a number of artists, the most notable were Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, and Roy Eldridge.

To understand how each of these new techniques developed, it is important to realize that at some point in the 1930s, improvisers such as Hawkins started to take on a far more vertical approach to soloing. Instead of focusing purely on crafting melodies, their soloing became more technical and reflected an understanding of both the sound and many different resolutions available between chords. In some ways they were trying to reflect the harmony as best as possible with only a single instrument. Of course this was paired with the common approach to improvisation at the time, resulting in a more complex form of soloing which required a strong understanding of theory and chord relationships. Out of this foundation, chromatic notes began to be formulated as not just individual passing or approach tones but as a part of chord sounds, being justified through new forms of substitution.

With this as our base, it is understandable how a concept like side-stepping could be created. The idea behind the technique is that on any given chord you move away from the chord tones by a semitone/halfstep momentarily to create tension before returning back. For example, if you had an F7 chord, to sidestep you would outline the notes of either E7 or Gb7 before then returning back to F7. The tension is not only created through the added chromaticism but also because the accompaniment would typically not move with the soloist, but more on that later. Eldridge was a big fan of this type of chromatic movement and had at least started implementing it into his solos as early as 1938 as seen in the start of his solo on Body and Soul with Chu Berry. Another wonderful example can be heard by Hawkins the following year on My Buddy with Lionel Hampton and his orchestra.

Body And Soul

Roy Eldridge Solo

My Buddy

Coleman Hawkins Solo

A natural continuation from side-stepping was the concept of tritone substitution where dominant chords could be replaced by those located a tritone away from the root (eg C7 to Gb7). To save myself from doubling up on another resource I’ve written, if you want more detail on the specific technique I’d suggest look at this resource. Interestingly, at the time it was common for chromatic approach chords to be used in big band arrangements which to some degree represent a similar sound when a dominant chord was being used. However, tritone substitution provided considerably more freedom and wasn't bound to the quality of a target chord. For example, a progression may go Ab7-G7 or Dbm7-Cm7 when using chromatic approach chords, where every chord is built on the same quality. Instead, tritone substitution only applies to dominant chords so a ii-V-I progression such as Dm7-G7-C would become Dm7-Db7-C. Yes there is still a level of chromatic resolution between each of the chords, however none of them share the same quality, allowing musicians to use tritone substitution in a greater number of contexts than chromatic approach chords.

It’s unclear exactly when tritone substitution became part of the improviser’s tool kit but it was definitely an established concept for Hawkins by 1939 when he recorded his definitive version of Body and Soul as a bandleader. In the second bar instead of a typical V-I resolution, you can clearly hear a bII-I resolution both being outlined by Hawkins as well as in the bass line while the piano maintains the original V chord. By using tritone substitution, he was able to outline the b9 and b5 in relation to the original chord, a sound which was quite rare outside of a select few players at the time.

Body And Soul

Coleman Hawkins Solo

This approach, similar to side-stepping, helped establish the third major technique soloists used in the late 1930s to add chromaticism: chord implication. Once artists such as Hawkins had got to a point in their ability where they were comfortable outlining the chords of a given progression, they began implying additional chord resolutions that were not being reinforced by the accompanying harmony. For example, instead of outlining a ii-V-I progression, an alternative option may be to play ii-bVI-VI-I with the bVI being implied by the soloist. Due to the nature of this technique creating obscure leaps to chords which feel unrelated at first, in most cases the choices being made only ever felt justified once a soloist had finally resolved back into the original progression. From there a clear resolution pathway could be identified but only after the fact, making the music feel considerably more adventurous with listeners being unsure of where a soloist might be going in real time.

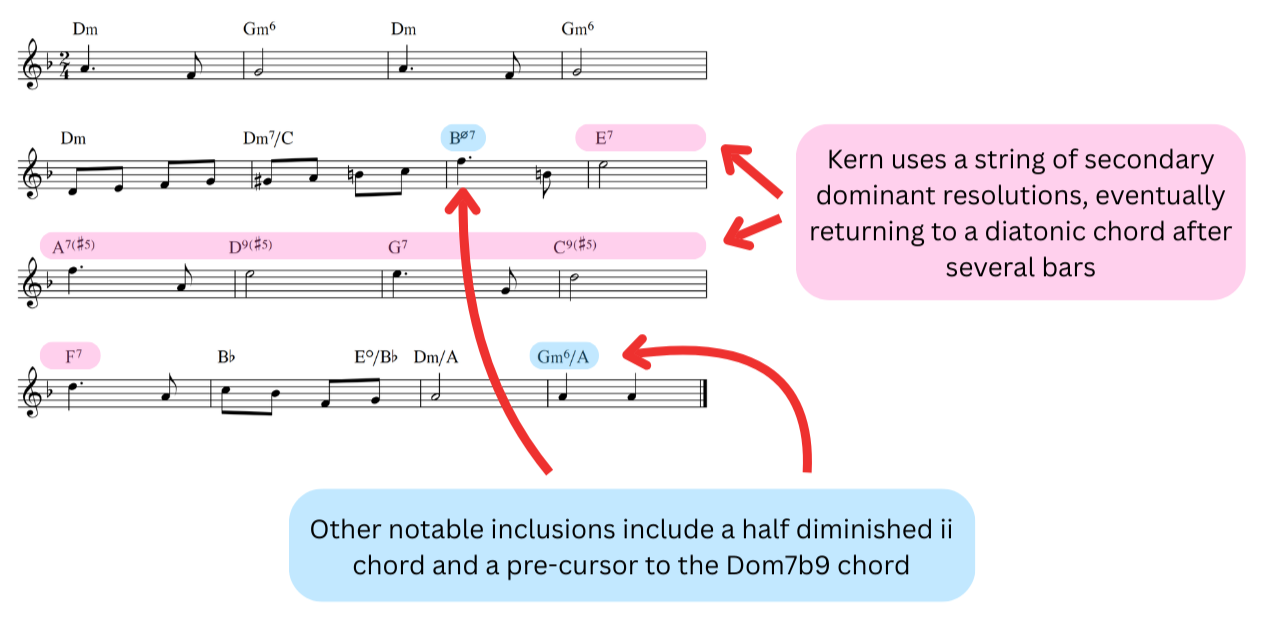

To fully understand the extent at which this technique was used it is important to also be aware of what was happening with harmony in American popular music in the 1930s. Thanks to composers such as Jerome Kern, the music of Broadway had started to incorporate a greater degree of temporary modulations to secondary keys within chord progressions. Unlike songs from previous decades, it was now common to see chord progressions break free from a single key and explore a variety of other tonal centers before eventually returning to where they started. Tunes such as Yesterdays, written by Kern in 1933, made use of multiple strings of secondary dominant chords, taking the listener through a number of different keys over the course of only 5 or 6 bars.

Yesterdays

Jerome Kern

As these songs were a significant part of a dance band’s songbook during the Swing Era, this sort of harmonic language would have been quite common for musicians such as Hawkins and Eldridge. It is no surprise then, that musicians would follow similar chord resolutions when implying chords in their solos and create large strings of either secondary dominant chords or ii-V progressions which eventually brought their solos back to the original chords of a given tune. Jumping ahead slightly, a perfect example of this is in Charlie Parker’s solo in Red Cross recorded by the Tiny Grimes Quintet in 1944. Instead of outlining the I-V-I progression in the A section, Parker implies a number of secondary dominant resolutions taking his solo from the home key of G major to as far away as B major in a matter of beats.

Red Cross

Charlie Parker Solo

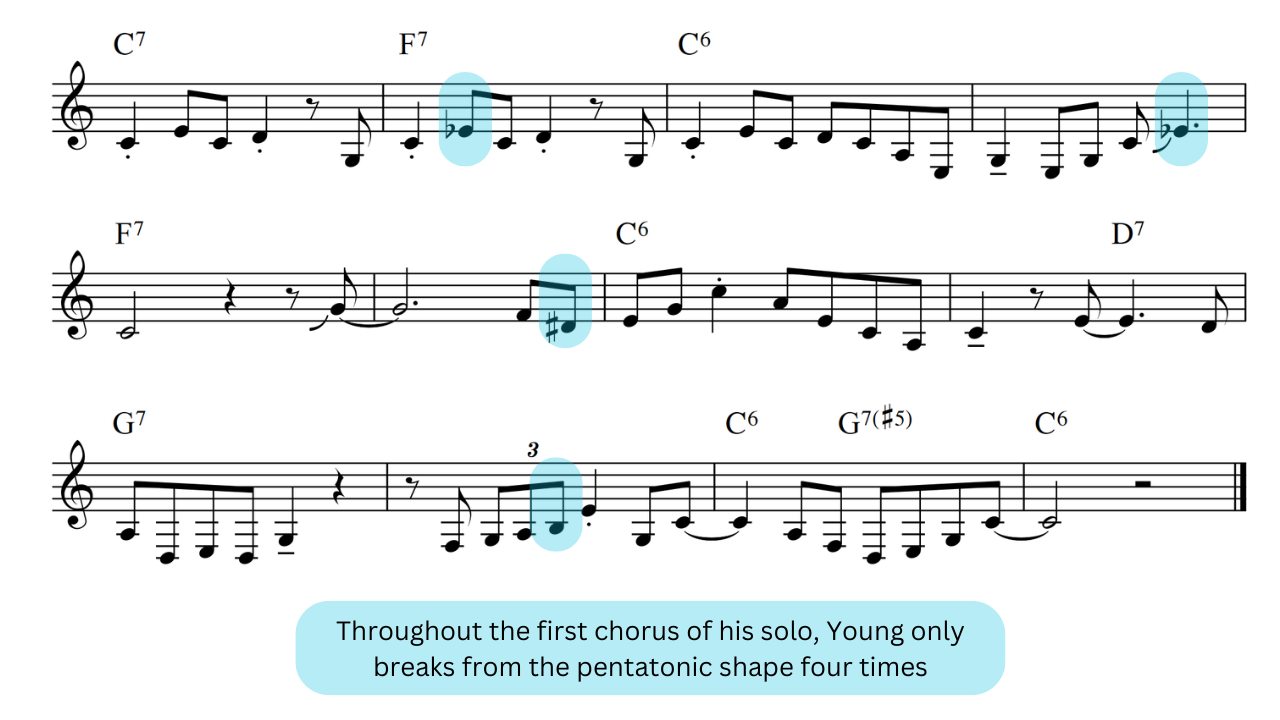

Eventually, this technique would be combined with both side-stepping and tritone substitution, as well as other concepts we will get to shortly, to create a considerably more complex harmonic approach to improvising. However, not all musicians in the late 1930s followed this path with Lester Young providing an alternative option. Instead of adding more harmonic density to a progression, Young went in the opposite direction and simplified his solos by playing harmonically ambiguous lines which could fit over multiple chord changes. For example, over a 12 bar blues he would lean heavily into pentatonic lines which featured the 6th degree of the home key. Due to the 6th being consonant to all of the common chords in the blues progression it wouldn’t necessarily outline any particular chord change or resolution but would still be a viable option.

Boogie Woogie

Lester Young Solo

As a result, when looking at Young’s solos it can be hard to know exactly how he thought about improvising. On one side we can be highly analytical and say he was outlining certain color tones and on the other we can say he was simply floating on top of the changes. Regardless of what Young actually thought, his approach to improvisation led to a significant concept which influenced bebop. By focusing on a set of notes that could be applied over multiple chord changes, he wasn’t bound to outlining specific resolutions allowing him to be more free with when he started and ended a phrase.

By combining the approaches of Eldridge, Hawkins, and Young, it is clear that the vocabulary of improvisation was pushing beyond what was established over a decade earlier by Armstrong. Solos were now becoming more vertical, creating a new landscape for chromaticism to be explored further than just passing chord tones and blue notes. The structure of phrases was also changing, moving from strict even blocks to a variety of lengths starting and ending where they pleased. Now it was time for these techniques to start being integrated by the next generation.

Underground Movements

Accompanying the bustling dance band scene of the Swing Era was a smaller movement of jam sessions held across the country. Depending on the venue, these jam sessions could happen at all times of the day but the most prolific and sought after were those held late in the evening which attracted the best players from the local dance bands. Unlike the big bands which had a set personnel, jam sessions featured any musician who wanted to show their prowess at improvising and prove their place in the music scene. With that said, there were informal filters such as private invitations and challenging music which weeded out the weaker musicians. Some of the methods used were to play pieces at faster tempos, change keys multiple times throughout a piece such as the infamous modulations up a halfstep/semitone after each chorus, and call tunes in uncommon keys, all of which forced newcomers to prove that they understood the music and could hang with the established in-crowd. While it may seem unfair to some, these conditions created the perfect breeding ground for creativity.

It is only natural that when so many gifted musicians come together regularly that new ideas spread, which is exactly what happened in the late night jams of New York. With that said, these interactions also took place on the bandstand as well as more obscure locations such as the rooftop of the cotton club between bassist Milt Hinton and trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. However, the jam session provided the perfect opportunity for musicians to experiment outside of the public eye, giving them the space to refine ideas with a like-minded group of individuals. Tired of the formulaic sound of the Swing Era, many musicians pushed jazz further by shifting the limits of the music. In almost every area something changed, such as what we just saw with chromaticism thanks to the likes of Eldridge and Hawkins, or phrasing with Young. But it didn’t stop there, articulation, rhythmic feel, and accompaniment roles all were impacted too, each of which being heavily associated with the innovations of newer players such as Charlie Christian, Charlie Parker, Thelonius Monk, and Kenny Clarke. It was a fertile arena where the music was changing fast, but before we look at where it ended up let’s take a second to unpack a few of the major contributors.

Up first is Charlie Christian, a guitarist from Texas who redefined the role of the guitar not only in jazz but in American music. As one of the first people to play the electric guitar, he moved away from the traditional approach of chunking on all four beats and gave the instrument a more melodic sound. Pioneering the use of single notes on the guitar, not only did he change the course of the instrument in jazz, he also is considered the foundation of rock ’n’ roll guitar playing and really everything that has come after that involves the instrument. Getting back to his influence on jazz, at a young age Christian was picked up by Benny Goodman which forced him to relocate to New York. Like many of the young musicians at the time, he frequented the late night jam sessions where he brought his rhythmic approach to the new music being created.

Unfortunately, Christian passed away far too young at the age of 25 and can only be heard in recordings from 1939-4. However, bootleg recordings from the jam sessions at Minton’s Playhouse provide an insight into his playing style outside of the Goodman sextet, revealing a unique approach to rhythm. Unlike the majority of swing musicians, Christian put equal emphasis on every subdivision, giving him a level of control over his phrases that didn’t necessarily always abide by the parameters of the time signature he was playing in. The overall effect was the creation of strings of rhythms which could start and stop at any one time. Although this sounds similar to the description of Young earlier, Young’s sax solos very much still reinforced the driving four feeling of the 4/4 meter, emphasizing strong beats more so than others. Christian’s playing on the other hand treated each beat equally, resulting in far more unorthodox groupings that didn’t reinforce the underlying time feel as much.

Right alongside Christian was drummer Kenny Clarke, who reinforced many of the syncopated rhythms on either the snare or bass drum. By the time the two came together at Minton’s, Clarke had already established a new style of playing where he would actively accompany the music with accented hits. This differed drastically from the status quo at the time which was simply to play time and no more. His experimentations began years earlier in the Teddy Hill band where he would look at trumpet parts and use various rhythms across the drums to set up their figures. Unfortunately for Clarke, the disapproval of his new approach actually led to him being fired from the band, however Clarke was hired later on by Hill as the house drummer at Minton’s. This new form of playing started to be referred to as “dropping bombs” due to the large accents on the bass drum and also led to the nickname “Klook,” which was a term that others such as Dizzy Gillespie used to describe some of the sounds of Clarke’s fills.

Not only did Clarke contribute a new form of accompaniment on the drums but he also was one of the first drummers to start using the ride cymbal as the main time keeping device. Supposedly, one night with the Hill band the tune Old Man River was called at a blistering tempo. Part way through Clarke realized he was not going to be able to continue playing the four-on-the-floor bass drum pattern with his foot and decided to move the time feel to the ride cymbal. After no comments from the band, he began experimenting further with the technique and set the foundations for the ride cymbal to replace the hi-hat as the main time keeping device in the latter half of the Swing Era.

Someone who very much needs no introduction when discussing bebop is Charlie Parker. Like Christian and Clarke, Parker also brought a number of new elements to the emerging style of music, namely in the form of phrasing and articulation. While many like to attribute Parker to far more than just those two areas, it is likely that other elements of his playing were a result of the influence of a number of the musicians. For example, it is common to point to Parker’s use of extensions and color tones, however while working as a dishwasher at Jimmie’s Chicken Shack in Harlem, Art Tatum was a regular performer at the venue which likely led to Parker’s use of such notes when soloing. Whereas when looking at phrasing and articulation, Parker provided a unique approach that can’t be found elsewhere.

What made his sound stand out was that he didn’t follow the standard conventions of playing notes legato or detached and instead opted for a more nuanced approach. Where improvisers would usually run up and down lines tonguing every note or slurring them, Parker created a new style of tonguing which accented the offbeats. Nowadays we call this jazz articulation but at the time this was revolutionary as it redefined how horns articulated when they played phrases. A simple way of thinking about the technique is by emphasizing the offbeat eighth notes/quavers and then slurring them into the downbeats.

But Parker didn’t stop there. He also utilized a variety of rhythms in his lines and paired this concept with dynamics and ghost notes to create interesting contours. The end result is a far more three dimensional approach to articulation and phrasing where an individual melody can be manipulated in dozens of different ways.

Sweet Georgia Brown

Charlie Parker

Returning to harmony, one of the major innovators in this department was Thelonius Monk who helped place dissonance at the forefront of jazz. Likely due to having the safety net of a family home in New York, Monk was able to develop his own identity without succumbing to the demands of the dance band industry. What resulted was a highly individual approach that sounded completely different from the dominant stride style of the time. Without going down the rabbit hole that is Monk, some of his notable contributions included championing the tritone as well as other dissonant intervals, establishing the iihalfdim chord as a viable option to improvise over (he thought of it as a ivm6 with the 6th in the bass), and adding a level of surprise into the music through the use of clusters. Interestingly, all of these techniques approached dissonance in a unique manner to how we explored earlier and created more pathways for musicians to navigate.

In addition to these developments, there is one other harmonic technique worth mentioning which is not actually linked to a particular person. As established in prior decades, modal interchange was very much a part of the sound of American popular music in the Swing Era, being used in a large percentage of classic Tin Pan Alley songs. You don’t have to go far to see the classic I-IV-iv-I progression where the iv is borrowed from the parallel minor key. However, somewhere along the line this concept developed into a slightly more complex variation by incorporating the bVII7 chord (also accessed through modal interchange) to create the iv-bVII-I progression. Unfortunately, there is no definitive start point that I’ve been able to locate for this transition but in the original score for Star Dust written by Hoagy Carmichael in 1927, there is a hint to this shift starting to occur in the chorus. Over four bars, Carmichael used the Fmaj - Fmin - Cmaj (IV-iv-I) progression but in the two bars allocated to Fmin, he placed the chord in an inversion alongside the 6th to spell out an Fmin6/Ab sound. Looking closely at these notes, there are many similar chord tones to Bb7 (bVII7) with the only note missing being the Bb. As such, the Fmin6/Ab gives off a similar sense of resolution and likely was a stepping stone for the bVII7 to be used in later compositions.

Star Dust

Hoagy Carmichael

Although we don’t know exactly when the bVII7-I resolution began to be used in the 1930s, it was very much present in the emerging jazz sound of the 1940s. Musicians such as Tadd Dameron used the device in his composition Lady Bird as early as 1939 and both Parker and Gillespie were utilizing the sound in their solos in early bebop recordings from the mid 1940s. For a large part of jazz history this concept didn’t have an official name but in recent decades it has picked up the “backdoor ii-V” title.

Lady Bird

Tadd Dameron

Coming from a similar background of modal interchange, popular tunes such as What Is This Thing Called Love? written by Cole Porter in 1929 started to highlight the b9 interval against dominant chords in minor keys. It should be noted that in the original sheet music these instances were very much not written as Dom7b9 chords, instead being justified through other means. However, important to the development of bebop, this repertoire created the foundation for diatonic extensions in minor keys to be used by the 1940s. In conjunction with Monk’s obsessions with the half diminished sound, somewhere in the early 40s the minor turnaround (iim7b5-V7b9) began to be implemented as an alternative to the common ii-V progression.

What Is This Thing Called Love?

Cole Porter

Thanks to these two specific developments, bebop musicians started to implement a mixture of major ii-V, minor ii-V, and backdoor ii-V progressions when resolving to a tonic chord. Each option was seen as a viable substitution for one another as long as the melody note fit within the new chord progression, giving the ability to set up surprise moments in the music. The technique was also paired with secondary dominant resolutions, giving considerably more chromatic options to the music. Interestingly, it was quite common for ii-Vs to never resolve, instead being cut off by a new set of resolutions taking the music elsewhere.

Finally, the last technique worth mentioning is the chromatic approach tone. As we’ve seen in both the melodies and improvisations of Early Jazz and the Jazz Age in previous resources, chromatic approach tones were an essential part of the vocabulary of jazz right from the start. However, in bebop they started to be implemented to a considerably higher degree. As improvisation became more technical with musicians outlining multiple chord tones, there were more situations where chromatic notes were necessary in order to maintain a string of eighth notes/quavers and make key resolution points. For example, over a G7 chord, if you were to run down all seven notes from G to G, you would arrive back at G on the and-of-4. Secondly, on every beat other than the first, the weaker chord tones (E, C, A) would be highlighted giving the impression that you weren’t outlining G7 at all but instead Am7. This posed an issue because most musicians preferred to arrive at fundamental chord tones on strong beats of the bar. In order to solve both problems, an extra note had to be added to the line, with the only viable option being to repeat a note or use a chromatic approach tone. Depending on the context either could be used, however the latter was considerably more popular.

These days it is quite common to learn this technique through the various bebop scales that have been created, but unfortunately like the blues scale, they offer a simplified outlook which doesn’t fully reflect the freedom of how bebop musicians used chromatic approach tones. While there are many examples of the technique being used in a similar manner to bebop scales, chromatic approach tones weren’t restricted to a certain part of a scale such as between the 5th and 6th degree and could be placed wherever the soloist deemed most suitable. As a result, there are many uses which fall outside of the scope of the bebop scale too.

As you can see, there were a considerable number of techniques being experimented with in the late night jam sessions of New York. Unfortunately, due to a recording ban which took place between 1942 to 1944, there is almost no evidence, apart from a handful of bootleg recordings, which demonstrate exactly how all of these components came together. However, once the ban ended, it was only a short time before the new jazz language was recorded, and when it was, one person championed it more so than any other: Dizzy Gillespie.

Bringing Bebop To The Masses

The transition from late night jam session to recording didn’t happen overnight though. In fact, it took multiple key events to bring bebop to the attention of the record labels, starting with the Harlem riot of 1943. After an incident of racialized violence, riots broke out across Harlem for two days, specifically targeting white owned businesses in the area. As a result, many of the performance venues relocated to midtown Manhattan, opening their doors on 52nd street. While this may seem like a major disadvantage for black musicians based in Harlem, it actually had a different long term outcome due to another event taking place with dance bands at the time.

During the same period, rates for dance bands were inflating at an increasing rate due to WWII. Americans were being asked to ration almost everything in order to support the war effort which often left them in an interesting situation where regardless of the amount of money they had access to, residents were restricted to the number of goods they could buy. An offshoot of this predicament was to spend more money on live performances, leading to record high ticket sales over the 1942-44 period. With more profits came the expectation of better pay for musicians, and over the two years the cost to host a big band at a venue skyrocketed. Eventually the bubble burst with ticket sales unable to match the demands of the dance bands. It was at this time that the popularity of big bands started to decline and smaller ensembles became favored, perfectly positioning the clubs on 52nd street which could only fit half a dozen or so musicians on the stage at one time.

Initially, the clubs hired known names in the jazz world such as the likes of Coleman Hawkins and Roy Eldridge to help attract patrons to the venues. However, both Eldridge and Hawkins often drew talent from the younger generation to make up their bands, which helped introduce musicians such as Dizzy Gillespie and Oscar Pettiford to the 52nd street scene. Thanks to Pettiford's relationship with the Onyx Club, in late 1943 arguably the first bebop ensemble premiered at the club and was co-led by Gillespie and Pettiford. The quintet brought a range of new compositions to midtown audiences including Round Midnight by Monk, as well as a large assortment by Gillespie such as A Night In Tunisia (known as Interlude at the time), Salt Peanuts, and Be-Bop. Interestingly, while this band was the first ensemble to present bebop in all its glory to the public, the first recordings of the style actually came in 1944 with other lineups such as those led by Coleman Hawkins and it wouldn’t be until 1945 when a similar five piece ensemble would properly represent the small group sound of the Gillespie-Pettiford quintet.

What we can see from these 1945 recordings by Gillespie and Parker is the first true representation of the new jazz language. Many of the components we have just discussed come together in each of the tracks as well as a few other notable characteristics. Departing from the big band tradition, the horns are orchestrated in a completely different manner to the swing bands of the time. Instead of harmonizing the melody, Gillespie and Parker play in octaves or unison throughout, allowing the complexity of the melody to speak. This wasn’t the first instance of such a technique being utilized with one of the most notable examples being the unison saxophone melody in Ellington’s Cotton Tail recorded in 1940, however it did become a staple in the bebop tradition.

Interestingly, there are still lingering remnants of the big band arranging tradition present in Gillespie’s writing with interludes and extended intros/outros being featured. In Salt Peanuts a short section of stop time is used to bookend the piece alongside two brief interludes after each melody chorus. It’s also worth mentioning that during the intro, Gillespie breaks from typical voicing conventions and voices the two horns in tritones, an almost unheard of approach for the time where 3rds and 6ths were the norm.

Salt Peanuts

Dizzy Gillespie

One last notable characteristic worth mentioning is the change in piano comping evident on the recordings. In the Swing Era stride piano dominated the sound of the big bands, however, Al Haig plays quite sporadically on the tracks, leaving plenty of room for the rest of the band to interact with one another. This style of comping didn’t originate with Haig and likely was the result of the pulse shifting from a two to four feel at the start of the 1930s. With the driving walking bass line and feathered bass drum, there was no need to reinforce the time feel with left hand stride patterns, giving the pianist opportunities to play more reactively. The technique most likely was perfected in late night jam sessions and was the final piece of the new rhythm section sound alongside the ride cymbal and snare/bass bombs.

As we can see in the 1945 recordings, the sound of bebop had left the realm of the big band behind and was moving in an entirely new direction. So you may find it surprising to hear that Gillespie was also a prolific big band arranger throughout the 40s, with some of the first bebop compositions actually being penned for the white band leader Woody Herman. In 1942, Herman commissioned Gillespie to write three charts for his band resulting in Woody ‘n’ You, Swing Shift, and Down Under. Unfortunately, only the latter was recorded but still gives an insight into Gillespie’s writing style prior to the bebop recordings of 1944. Perhaps more importantly, the members of Herman’s band loved the new direction of bebop and started to try and capture the sound in their own compositions, particularly a young Neal Hefti who played trumpet with the band. Some notable examples of this include Caledonia and Apple Honey.

A few years later in 1944, Gillespie also wrote a number of arrangements for the Billy Eckstine band whilst operating as the musical director. Although the arranger credits for Good Jelly Blues are not stated, listening to both the intro and background lines it is clear that a bebop minded writer was behind the chart, most likely being Gillespie. And for those familiar with his recording of All The Things You Are in 1945, you may notice some striking similarities between the start of both recordings.

With the dream of some day running his own big band, in 1945 Gillespie pursued the idea in collaboration with arranger Gil Fuller and combined his love for large ensemble arranging with the sensibilities of bebop. To be expected, the band was a huge failure as audiences didn’t understand the new approach. That didn’t deter Gillespie though, and in the following year he tried once again to find success as a big band leader. This time around, his efforts were more successful and he was able to keep his band going until the end of the 40s. In my opinion, this particular band represents some of the most exciting big band music of the Swing Era, inputting a considerable amount of experimentation back into the format by combining elements of bebop, cuban music, and swing together. Just take one listen to Things To Come or Manteca and you’ll see how different Gillespie’s band sounded to the popular bands we discussed in the previous resource.

These days bebop is given a considerable amount of attention, but in the 1940s it actually was not that popular. At a time when the swing was losing its appeal thanks to new styles such as rhythm and blues, any developments in jazz were almost undetectable in the bigger picture of American popular music. Due to the complex nature of bebop, the style alienated most audiences and was primarily listened to by aspiring musicians or die hard fans. As a result, many of the major names associated with the new movement died young with little to no recognition, only to become living legends once the significance of their contributions was realized decades later.

Bebop didn’t die at the end of the 1940s though. Instead it transitioned into the foundational language for improvisation which became the basis for a new wave of small group jazz in the coming decades. Through musicians like Miles Davis, bebop continued to live on in new styles for decades to the extent that many of the key developments made by the bebop pioneers still live on in jazz today. It can’t be stressed enough how important bebop was for the trajectory of jazz history. So while the style may not have been popular at the time of its inception, ultimately Gillespie achieved his goal of creating a modern improvisational language that would redefine jazz completely.

The Takeaway

Started by a generation of young musicians who wanted to push jazz in a new direction, bebop truly is one of the special moments in jazz history. Against all odds, the music was able to break free from the late night jam sessions and seep into every nook and cranny of the art form. No area was left untouched with significant changes taking place in harmony, rhythm, articulation, phrasing, orchestration, and instrumental roles. While the music may not be for everyone, I think it’s safe to say that most people can see the tremendous legacy musicians such as Parker and Gillespie have left behind. I’m so glad that even though my introduction to bebop may have been rough, in the end I was able to come around and see the true beauty of the developments that took place.

The years that followed bebop’s heyday were some of the most creative in jazz history, with many new styles being created in the 1950s such as Hardbop, Modal, and Avant-Garde. In the pursuit of exploring each of them in detail, I’ve chosen to break up the 1950s into a number of individual resources like this one. Up first is Cool Jazz, the invention of Miles Davis, Gil Evans, and Gerry Mulligan which took the sound of bebop in a completely new direction.