The Standout Techniques Which

Defined The Sound Of Cool Jazz

When we think of Cool Jazz there is one album which comes to mind, “Birth of the Cool” by Miles Davis. Probably because many see it as the album which launched the entire genre as well as established the name. But what is Cool, and how does it differ from the styles that came before? If you’re like me, the term can feel somewhat ambiguous and the more you look into defining the sound it becomes quite confusing. As one of the first major post-bop styles, Cool occupies a special place in jazz history and surprisingly is more relevant to current jazz arranging and composition trends than most other styles from the 20th century. Through writers such as Gil Evans and Gerry Mulligan, the innovations of bebop were transformed into a completely unique sound that offered a new direction for jazz composition. However, while Cool has created ripple effects in modern jazz, it often competes with other styles from the same period such as Hardbop and Modal Jazz for attention from the wider jazz audience.

During my teenage years I never really had an awareness of the style, nor the albums associated with it. Like many, I stumbled onto “Kind of Blue” pretty early on but didn’t look into Miles that much further. Instead, I spent more of my time listening to Basie and Sinatra, as well as more contemporary releases. That all changed though in my first semester at university where I took a class dedicated to jazz recordings. Being one of the seminal albums in jazz history, it is no surprise that “Birth of the Cool” was mentioned. Due to the sizable recording library at the college, after every class I was able to go and borrow the albums covered, stockpiling them for listening at a later date. While the class was great at introducing me to a lot of music I had simply never heard of before, due to the overwhelming number of albums covered, unfortunately “Birth of the Cool” went untouched for a number of years.

Then one day in my penultimate semester, my roommate expressed interest in performing the entire “Birth of the Cool” album as a recital. Seeing the vision, I jumped into action and started putting together the pieces. Due to the nature of the music, it was easy to convince some of the best players at the university to come on board, including multiple doctoral students and even a faculty member. That left me with one big problem, I didn’t really know anything about the music we were playing, let alone how to lead a group of players through it all. Not to mention one of the conditions of the recital was that it had to be a mixture of music from the album as well as a number of arrangements in that style. Going off the musical suggestions of one of the arranging teaching assistants, I tried writing for the instrumentation of the ensemble and hoped that it would be good enough for the concert. Somehow we all got through it, mainly because the musicians I had booked actually knew something about the music and saved me from utter embarrassment. However, for many years that was my only taste of Cool Jazz, with life taking me in other directions after the recital.

My hiatus with Cool lasted close to a decade, filled with explorations in many other musical directions. The name Gil Evans often came up during that period, but due to the busyness of life, any time I looked for inspiration it was with more familiar arrangers such as Quincy Jones. However, the recital all those years ago had planted a seed of interest that was slowly growing and eventually led me to dive deeper into Evans and his other projects. It’s hard to describe the feeling of listening to his music for the first time but coming from a background steeped in the Basie tradition, when listening to his earlier arrangements for the Claude Thornhill band, my jaw hit the floor at how amazing the music sounded and how completely different it was to any of the other Swing Era bands. This experience inspired me to look even further and around every corner was another amazingly refreshing gem.

In this resource my aim is to explore some of the amazing characteristics of Evans and his writing captured in those early recordings and how they helped to establish the entire Cool genre. While there are many other artists that fall under the Cool category, a majority of the elements of the style were first created through the Thornhill and Miles Davis Nonet sound, so I have chosen to focus primarily on those two ensembles with a small detour to discuss Gerry Mulligan. There is a lot that can be said about Evans specifically, but I’ll leave an exploration of his entire body of work, notably the later collaboration with Miles at the end of the 1950s, for a later time.

What Is Cool Jazz?

Like many, for years I thought Cool Jazz was specifically a label to describe the sound of the “Birth of the Cool” album, not realizing it is its own category of music that actually encapsulates a considerable amount of other artists. Yes, Miles and Evans are a major component of the style but through their influence there are actually over a decade's worth of other artists that are also considered as part of the Cool banner. These include many of those involved in the original Miles Davis Nonet such as Gerry Mulligan, John Lewis, and Lee Konitz, but also extends to others such as Lennie Tristano, Dave Brubeck and Chet Baker, among many others.

One way which has helped me understand the term is to think of it in a similar way to how the words hot and sweet were used in prior decades, instead of associating Cool in a similar capacity to styles such as bebop or hardbop. The word is far less critical of certain characteristics and is applied more broadly, making it somewhat confusing to nail the specific traits that make up the sound. In general, Cool musicians are linked with one unifying factor, that they have a more relaxed approach to playing bebop inspired jazz. A fantastic example of this is to compare the sound of Konitz to Charlie Parker, two outstanding alto saxophonists, but with two drastically different tonal concepts. There is a higher level of intensity with Parker, almost as if the lines he plays have to resolve more urgently or be emphasized to a greater degree. Whereas Konitz offers a smoother approach to the same vocabulary, with each note being rounded off. For an even starker difference, listen to the sound of Paul Desmond in comparison to Parker.

Outside of this particular element, the various artists within the Cool bracket actually showcase considerable differences when it comes to their music. For example, the music of Tristano pushes the limits of tonality and meter in a completely different direction to Evans. Although there are some similarities between the artists, a side-by-side comparison reveals two drastically different angles to the Cool category.

These days it can be quite confusing knowing what to title certain artists and their music. After the creation of bebop, jazz moved along a number of different paths, some of which had defined styles and others being more broad such as Cool. At the end of the day, the styles and titles assigned to music is a secondary issue compared to the actual music itself and should only ever be thought of as a tool to help us organize the many different approaches that exist. When Evans and the other pioneers of Cool got together, they didn’t call it Cool, they simply had a musical idea which later was marketed by a record label as Cool and the rest is history.

Claude Thornhill & His Orchestra

Unlike other bands of the Swing Era, Claude Thornhill’s group often gets very little mention in jazz history. While they weren’t as popular as Glenn Miller or Tommy Dorsey, they still maintained a considerable presence in the large ensemble jazz scene and were often voted as one of the more popular ensembles of the time. Interestingly, the ensemble started with a completely different concept than the majority of dance bands, drawing more from contemporary classical music than the riff based passages of the Kansas City sound. As such, much of their music fell into the sweet category which may be one of the reasons jazz history hasn’t been as kind to Thornhill in comparison to others.

Established at the inception of the band, one of the major differences that Thornhill brought was the inclusion of two clarinets alongside a 4-piece reed section. At times they could be utilized as a mighty 6 person clarinet section, giving an incredibly unique sound to the band in comparison to anything else at the time. Due to the popularity of Miller using a clarinet lead in his reed section, Thornhill’s clarinet heavy approach quickly gained recognition from the American public, enabling the band to continue in a more symphonic approach. With the power of hindsight, in 1941 one of the most impactful decisions for the band’s trajectory was made. Evans was approached by Thornhill to assist with the arranging for the ensemble and joined as chief arranger shortly after.

At the time, Evans had spent a number of years running a mildly successful band in California that operated as his main vehicle for composition and arranging. With no formal composition training, he learned by meticulously transcribing the works of all of the great bands of the 1930s, which inevitably turned into experimentation with instrument combos and harmonic ideas. Well before his tenure with the Thornhill band, Evans had already started having his band use uncommon woodwind doubles such as flute and oboe, with no option being off the table. Drawing inspiration from the sounds of Duke Ellington, Sy Oliver with the Jimmy Lunceford band, Eddie Sauter with the Benny Goodman band, as well as contemporary 20th century classical composers such as Ravel, Debussy, and Manuel de Falla, the harmonic palette of Evans was unlike most jazz composers at the time. A fantastic example of this can be heard in the intro to Strange Enchantment recorded by Skinnay Ennis in 1940.

Unfortunately, only a year after Evans came on board with the band, Thornhill enlisted with the navy and the group was broken up. Evans soon followed suit and also joined the military for a number of years. After returning to civilian life, Thornhill started up the band once again and rehired Evans in 1946 upon his relocation to New York. Even though Evans had contributed a number of titles to the ensemble prior to WWII, the period afterward is more noteworthy due to the musical developments of bebop. Having moved into a city apartment close to the clubs on 52nd street, Evans quickly fostered relationships with a number of musicians including Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. He was enthralled by the new sound of jazz and wanted to capture it within a large ensemble sound. Fortunately, Thornhill’s band provided the perfect testing ground for such an idea.

Coinciding with Parker’s return to New York in 1947, Evans was entrusted with more responsibility with the Thornhill band. He now ran all of the rehearsals, wrote a majority of the arrangements, and had the freedom to explore his artistic vision within the confines of the ensemble. Building off of the symphonic sound that Thornhill had created, Evans decided to expand the band by adding a tuba. With the addition of two french horns prior to WWII, the Thornhill group was now considerably different to other big bands and leaned toward a woodwind heavy and orchestral brass sound. It was with this palette that Evans started applying the concepts of bebop, creating a new approach that differed from the large ensemble sound Gillespie had established with his big band.

Before getting into exactly how Evans crafted his new bebop inspired arrangements, it would be wise to explore the specific approach of the Thornhill band to better understand how exactly it differed to a typical big band of the Swing Era. Not only did the band have an unconventional lineup, it also approached playing music in a drastically different way to other dance bands. Coming from a background of playing ballads, Thornhill had pushed the ensemble to take on a more classical approach to playing swing music. Augmented by a large woodwind section that often played in the middle to low register, the overall sound of the band was quite lush and played in a relaxed manner compared to the piercing high brass featured in many of the major Swing Era bands. To match the mood established by the woodwinds, the brass were also written in their middle to lower register and often used mutes, namely the hat mute which dampened the sound further. When the french horns were added in 1941, the arrangements started to highlight the new timbre, utilizing horns on lead lines alongside the reeds. And once the tuba joined the ranks in 1947, Evans chose to not write for the instrument in the conventional 1920s two feel approach and instead used it too as a contrapuntal voice with melodic counterlines.

To push the sound of the ensemble further, Thornhill went against the common vibrato conventions and had the band play with little to no vibrato. A stark difference to the wide oscillating approach that Guy Lombardo had established and which was popular throughout big band music at the time. Additionally, the Thornhill band was known for its fluid use of dynamics, capturing a more classical approach that ebbed and flowed and provided drastic shifts to the music. The combination of all of these elements gave the ensemble a signature sound, which surprisingly was quite popular even though it differed in many ways from the status quo. A great example of this sound can be heard in Evans’ arrangement of There’s A Small Hotel recorded in 1942.

With Thornhill’s band as his base, it’s no surprise that any sort of combination that Evans was able to conjure up between bebop and the established sound of the ensemble would lead to unique results. Interestingly, in the late 1940s the concepts found in bebop were primarily utilized by improvisers more so than composers. With the exception of a handful of writers such as Gillespie, there was really no established format for the style outside of the small groups that lived on 52nd street and in the late night jams of Harlem. By arranging a number of Parker’s compositions such as Anthropology and Yardbird Suite, Evans provided an alternative approach to large ensemble bebop.

At the time only a small number of musicians in New York could actually capture the sound of bebop accurately, with most of the Thornhill band falling outside of that group. Evans’ solution was to bring saxophonist Lee Konitz into the band, someone who understood the intricacies of modern jazz and could help the other members. Additionally, Evans meticulously wrote every articulation and phrase marking based on how Parker approached playing, allowing musicians with no knowledge on bebop to somewhat accurately capture the sound of the style.

Due to the high density of notes being played at fast tempos, it was common in bebop to feature unison and octave voicings to allow the lines to speak and not be weighed down by harmony. While Evans did stick to this convention to a degree, he would also harmonize the full band, including writing moving lines for both the french horns and tuba. To do so, he used a variety of passing chord techniques over a walking bass part which outlined the functional harmony. Compared to the common arranging techniques in use at the time, Evans pushed the harmonic boundaries further than most, making use of multiple chromatic extensions and tritone substitutions within his passing chords. The result was a highly colorful realization of bebop vocabulary where the harmonic techniques used in the solos of musicians like Parker and Gillespie were applied vertically to harmonize a full big band.

Evans also departed from the conventional block voicing techniques of the time, instead using a mixture of shapes dependent on the context. For example, in the band interlude in Anthropology he starts off with block voicings for the majority of the band with the tuba part highlighting the functional harmony while still playing homophonically to the rest of the ensemble. However, in the second half of the section there are moments where Evans is thinking more about the individual lines of the inner parts, creating some unusual shapes which can only be justified through the melodic nature of each line. In the same passage he also uses quartal and open voicings, two techniques more commonly found in 20th century contemporary classical music than jazz at the time.

Anthropology

Arr. by Gil Evans

Apart from a unique approach to harmony and voicings, Evans followed the mindset of the late 1920s arrangers by interweaving solos with band figures. While not as groundbreaking as other aspects of his writing, this shift marked a return to emphasizing soloists in an arrangement more so than the 4 or 8 bar sections that had become the norm in the Swing Era. His arrangement of Yardbird Suite recorded in 1947 is a fantastic example of balancing solos with band figures, allocating about half of the arrangement to both.

Although the bebop inspired arrangements of Evans are spectacular, they were not the only charts he wrote for Thornhill post WWII. Instead of the influence of Parker or Gillespie, he looked to classical composers and adapted components of their compositions for the ensemble. One such example is Troubadour which is based on Mussorgsky’s Pictures At An Exhibition. You don’t have to listen long to notice the stark difference in textures explored by Evans, who makes full use of an 8-piece woodwind section filled with flutes, clarinets, bass clarinets, and a piccolo in the first few bars. It is in these classical inspired arrangements that Evans really embraced the full range of textures at his disposal, making the typical swing big band arrangement feel quite bland in comparison.

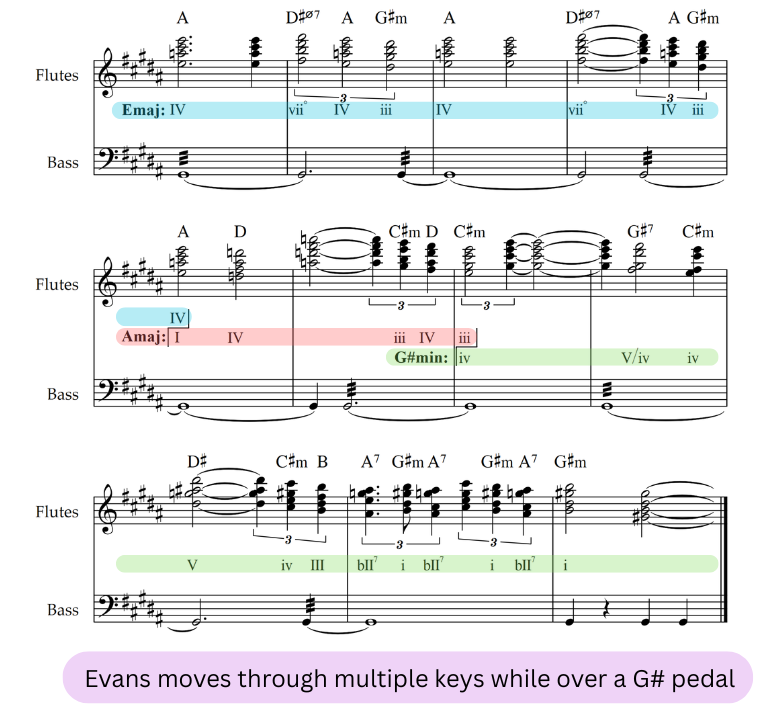

Like we explored with Anthropology, Evans also utilized a variety of harmonic techniques in this side of his writing too. Unlike earlier though, a completely new array of approaches were used which resulted in a much more orchestral sound. For example, the majority of Troubadour is set against a G# pedal in the bass with Evans shifting the harmony above into a number of different keys. Although the moving harmony generally modulates through pivot chords quite smoothly, Evans is able to create dissonance through the relationship between each chord/key and the underlying bass part. A particular striking moment is when the flutes are voiced in an A major triad over the G# bass, bringing a lot of attention to the highly volatile m9 interval.

Troubadour

Gil Evans

The overall effect of both the bebop and classically inspired pieces combined with the Thornhill approach and the diverse instrumentation led to the creation of a completely new sound that would later be described as Cool Jazz. However, in the late 1940s it was only considered the signature sound of the Thornhill band and it would take another decade before it would become a standalone category. For that to happen though, a number of events had to take place, many of which started in Evans’ New York apartment.

Birth Of The Cool

For the first couple of years following Evans relocation to New York, not only did he write for the Thornhill band but he also consistently discussed ideas with a small community of likeminded musicians in his apartment. As mentioned earlier, the apartment was located only a few blocks from the thriving 52nd street jazz scene making it one of the go-to hangout spots for musicians. Evans also had an open door policy where he would leave the room unlocked at all times regardless of whether he was there or not, making the space available for anyone who needed it. Naturally, Evans attracted many of the up-and-coming musicians who were keen to share new concepts with one another. At first some of the regulars included Gerry Mulligan, John Carisi, and George Russell, but over time it grew to expand many others such as John Lewis and a young Miles Davis.

Somewhere along the line, the idea of capturing the Thornhill sound with a smaller ensemble was raised. A band that had just enough instruments to allow arrangers access to the diverse textures found in Thornhill’s big band. At first Evans had the idea to use three saxes (alto, tenor, bari), all of which could double on clarinet, alongside french horn, trombone, two trumpets, and a standard rhythm section. However, over time the lineup was refined to alto, bari, french horn, trombone, tuba, trumpet, and a 3-piece rhythm section. At first the small band was just a concept, but that all changed when Miles started frequenting the apartment in 1948. Although Miles was known as a bebop musician at the time, he had a different concept to playing the trumpet compared to other boppers like Gillespie or Howard McGhee. Evident by his recordings with Parker such as Half Nelson and Sippin’ At Bell’s, Miles had a much smoother approach and rarely played in the upper register. He became the ideal candidate for the new small group concept and once he heard about the idea, he decided to make it a reality.

As the idea had been discussed at length by the time Miles came on board, most of the ideal personnel had been thought out. Fortunately, it just so happened that Thornhill broke up his band temporarily around the same time, freeing up multiple members to be incorporated into the new small group. The leftover positions were then filled out by Miles who drew on his connections in the bebop world. As a result, the band had an eclectic array of musicians including the likes of Lee Konitz, Max Roach, John Lewis, and Gerry Mulligan. With Miles taking charge of the management of the ensemble, rehearsals were scheduled and before long a performance was lined up at the Royal Roost. It just so happened that at the small set of gigs, a representative from Capitol Records was present and signed the band to record twelve tracks with the label.

At the time, many of the regulars at Evans’ apartment contributed arrangements to the group, giving the ensemble a diverse lineup of repertoire to record. Both Mulligan and Lewis wrote the lionshare, but Carisi and Evans also brought in one or two each. Likely due to time constraints, some of the arrangements were reductions from the Thornhill library while others were completely new for the nonet. Despite the differing arranging styles, the unique instrumentation and approach gave a unified sound which helped bring a level of cohesiveness to the twelve tracks. Coming out of the Evans/Thornhill mentality, the arrangements naturally drew upon many of the techniques we explored earlier, however there were plenty of new approaches used too, likely the result of the many discussions the arrangers had in Evans’ apartment over the years.

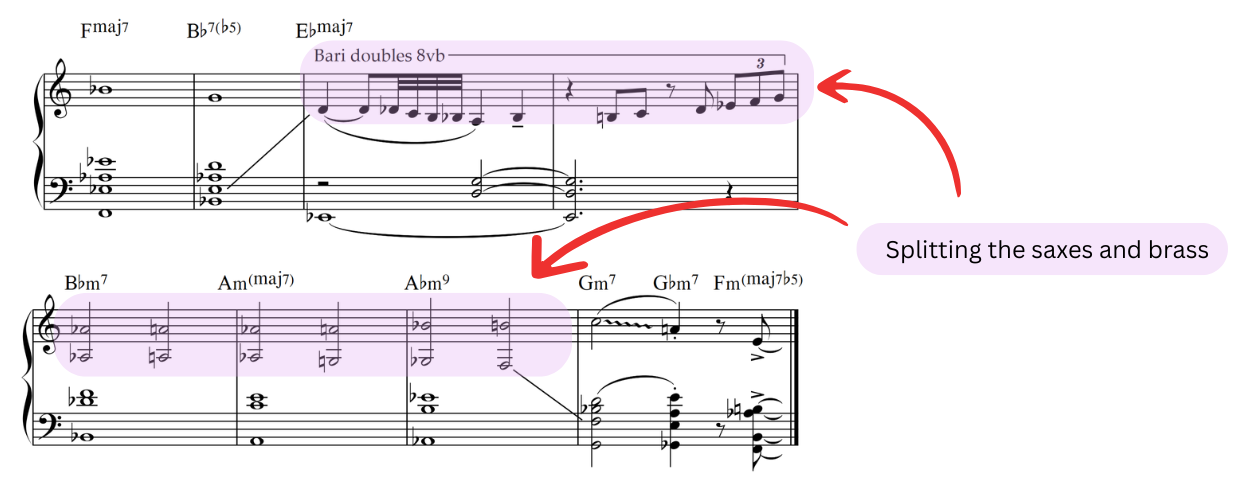

By embracing such a diverse range of instruments, naturally the arrangers were able to group them in multiple combinations. Over the twelve tracks a number of options were commonly used, including using all of the horns together, splitting the saxes from the brass, grouping similar registers together such as trumpet and alto, trombone and french horn, or bari and tuba, as well as isolating individual instruments for solos while the other horns operate as a collective behind them. Interestingly, even though the original Thornhill sound utilized an abundance of woodwind textures and muted brass, no doubles or mutes were ever utilized by the nonet.

Jeru

Gerry Mulligan

Deception

Arr. by Gerry Mulligan

Godchild

Arr. by Gerry Mulligan

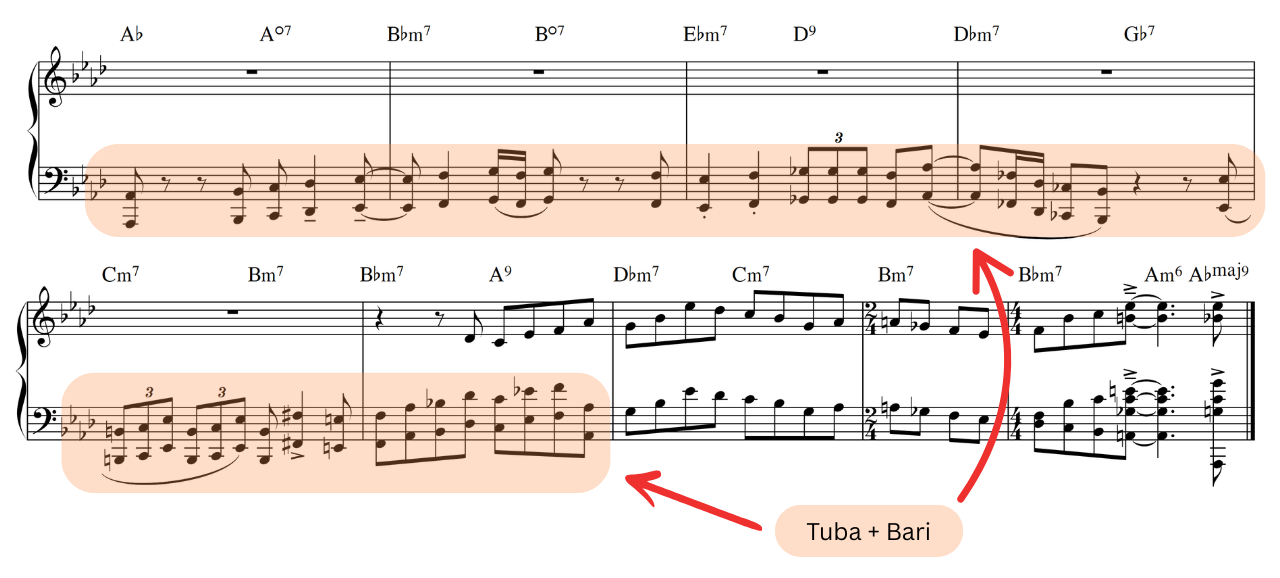

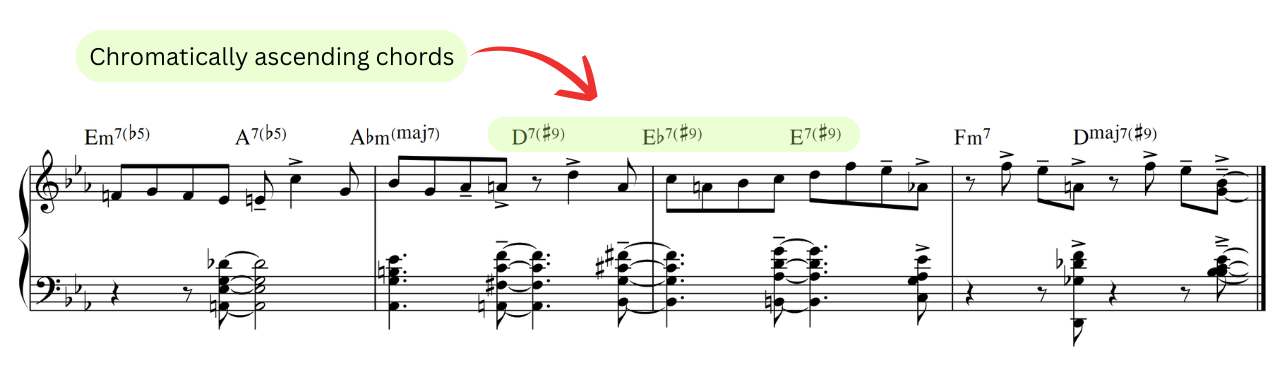

Other than orchestration, the twelve arrangements boasted a myriad of harmonic techniques, some drawn from what Evans had already established with Thornhill while others were more in line with the modal theory concepts that George Russell was pioneering. The harmony prioritized chromaticism with an abundance of alterations and extensions being used on every chord. Sometimes the chords would be connected in a functional manner, however there was also a prominent use of chromatic approach chords, particularly from below the target chord, as well as the use of non-functional modal harmony. The combination of all of these factors led to a lush harmonic palette which sounded unlike any kind of jazz that had come before and even made the classically inspired works that Evans had written for Thornhill feel tame in comparison.

Jeru

Gerry Mulligan

Deception

Arr. by Gerry Mulligan

The harmony was also further complicated by the use of passing chords in the horn parts. A common technique when all of the horns played homophonically was to have the tuba part play notes linked with the underlying chord progression while the rest of the section outlined various passing chords. This enabled all of the parts to move at the same pace but ensured that the tuba wouldn’t clash with the walking bass line.

Boplicity

Miles Davis & Gil Evans

Although the band did make use of a 3-piece rhythm section, none of the creativeness expressed in the horn writing made it into the three parts unfortunately. When looking at the piano parts, the chords can sometimes seem somewhat unconnected to each other too, primarily because they are not actually the full chords being implied by the horns and bass part, and only represent the specific colors the given arranger wanted the piano to reinforce. It is surprising that while the horns demonstrate an extraordinarily colorful harmonic palette that the same isn’t reflected in the piano. Years later, Mulligan commented on the topic saying that he regretted not making more use of the instruments.

Combining the orchestration techniques, colorful harmony, the relaxed Thornhill sound of no vibrato and instruments being voiced in their middle to low register, alongside bebop vocabulary created a groundbreaking new approach to both jazz arranging and performance. However, when the first few tracks were released by Capitol, the general public did not share the same opinion and the recordings were seen as a commercial failure. For years they sat untouched until 1957 when they were released as a full LP album titled “Birth of the Cool.” Thanks to the rise in Miles’ popularity over the passing years, the album gained considerably more traction and ushered in the official name for the Cool style. The album release also led to further collaborations between Miles and Evans that have now become legendary in jazz history, but that will have to be discussed in a later resource as it lands outside of the scope of Cool Jazz.

Expanding The Style

Between the recording of the twelve nonet tracks and the release of “Birth of the Cool,” many other musicians also latched onto a more relaxed post-bop sound. Some came from the original nonet lineup such as Lee Konitz, Gerry Mulligan, and John Lewis, whereas others created their own approach that just so happened to share many of the same musical qualities. For much of the late 1940s and early 50s though, these artists were simply considered as part of the post-bop movement and were only categorized as Cool musicians once the name was created in 1957.

Having established himself as a prolific arranger with Gene Krupa, Elliot Lawrence, and Thornhill in the second half of the 40s, Mulligan decided to relocate to California shortly after the “Birth of the Cool” sessions. He found himself surrounded by a new group of likeminded musicians and together helped establish the West Coast Jazz style, an offshoot of Cool with almost identical musical characteristics. Thanks to the break up of the Stan Kenton band in 1950 which resulted in multiple of the band members staying in California, alongside Mulligan some of the pioneers of West Coast Jazz included Art Pepper, Shelly Manne, and Shorty Rogers.

One of the first groups Mulligan put together in California was a quartet with Chet Baker on trumpet, Bob Whitlock on bass, and Chico Hamilton on drums. Unlike his prior groups, this particular band had no chordal accompaniment and focused primarily on implying harmony through the three melodic instruments. To do so, each part had a definitive role. The bass generally emphasized the root as well as other fundamental tones while one of the horns took a melody line which covered the other functional harmony notes. The remaining horn was then free to play some sort of contrapuntal line or could harmonize the melody, with both options outlining further chord tones. The result was a much lighter ensemble sound which still had the ability for harmony to be heard. Mulligan paired this harmonic approach with soft dynamics, making the band come down to the volume of the string bass and persisted for the use of brushes on the drums. Some examples of this approach include the quartet’s recording of Bernie’s Tune and Lullaby of Leaves both from 1952.

Bernie’s Tune

Arr. Gerry Mulligan

Mulligan would go on and run many more ensembles in the coming decades, each of which capturing some level of the magic that was created in the original “Birth of the Cool” sessions. For the most part, the Cool style was primarily defined by a relaxed playing style with many different artists providing a variety of interpretations. Some leaned more towards bebop, while others had more simplified harmony. Artists such as Lennie Tristano pushed the harmonic language in a different direction completely, opting for angular lines and a strong association with scales and modes in their improvisations. Others like Dave Brubeck looked outside of harmony and used uncommon time signatures and rhythmic groupings. Regardless of the specific direction one chose, as long as the overall feeling felt light then it was considered a part of the Cool category.

The Takeaway

Cool Jazz is yet another fantastic style within the jazz world that sounds unlike anything that came before. Positioned with a new vocabulary thanks to the creation of bebop, Evans and Miles very much established a new way to utilize the skills developed by the likes of Parker and Gillespie. Although their work may not have been recognized for almost a decade after they recorded the seminal “Birth of the Cool” album, today we can see just how important their concepts were, so much so that the music of many modern day arrangers can be traced back to the techniques Evans was using in the 1940s.

However, Cool was not alone. In the late 1940s another post-bop style was created which leaned more heavily on the blues and offered a contrasting sound. But that will have to wait for the next resource where I go into Hardbop in more detail.