(Apr 18 2025) What To Do When You Want Your Chords To Feel A Bit More Modern

There’s one harmonic technique that I’ve been obsessed with a lot recently, not just because it seems to be a crowd pleaser, but because it is highly effective at establishing a mood for very minimal effort. It is built around a non-diatonic modal concept that Bill Evans leaned on a lot in his compositions and piano playing but is also completely applicable to arranging. If you like the sound of Kind of Blue, it comes from a similar type of approach but takes the sound a step further and creates some really rich harmonies.

So back at university, a few too many years ago now, I walked into an arranging class not knowing what to expect. Each week we covered a different unique topic and although I had seen the syllabus for the semester, that was the last thing my heavily sleep deprived self could recall. However, what Rich DeRosa showed me that day has stuck with me ever since.

The main concept he introduced was the idea that you can harmonize any melody note with some kind of modal chord shape. Dorian and Lydian are the most common due to the structure of the associated chords (now that I’ve experimented with the technique over a number of years, I imagine you could probably stretch the concept to all of the modes of the major scale to some degree). As a result of this type of harmonization, he explained that you can create a chord progression which doesn’t resolve functionally but is built on similar sounding chord shapes, albeit all related non-diatonically. I’m sure Rich mentioned a name for the technique, but if so, it has now been forgotten and I just refer to the sound as modal harmonization.

Sometime after taking the class, I ran into a video of Bill Evans explaining one of his approaches to reharmonization. To my surprise, it actually matched with exactly what Rich had taught in the class and I immediately was able to draw the connection between the concept and a number of practical applications. The way Evans described his process was to take a melody note and to think of it as the #11 of a maj13#11 chord (the Lydian sound). I believe he then went on to demonstrate the idea by playing a standard like Autumn Leaves.

To my ears, there really isn’t anything quite like the results you are able to pull from using this technique, and when you hear Bill Evans, I believe it is one of the major characteristics of his sound. So how can you start incorporating it into your own writing? Fortunately, it is quite simple.

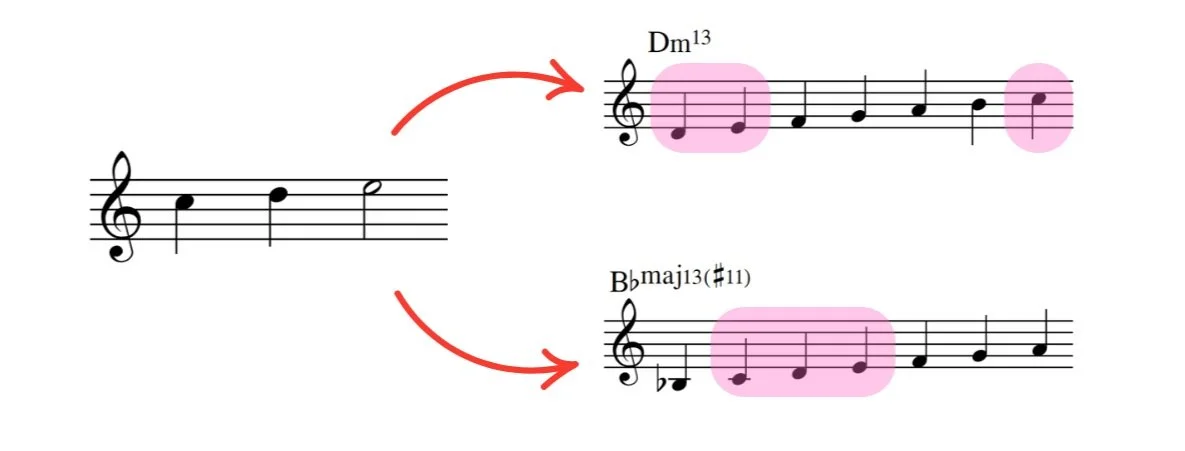

Similar to what Bill Evans described in that video, all you have to do is interpret a melody note, or set of melody notes, as being in a certain mode. For example, if you have a C in the melody, that could be a chord tone of multiple different Dorian or Lydian chords. To make it feel like Dorian, assign some kind of min13 chord, and for Lydian, a maj13#11. You can choose which chord tone, but in general if the melody note is thought of as an extension in either chord option, it will feel far more colorful. So taking that C, you could think of it as a #11 in Gbmaj13#11, or perhaps as an 11 in Gm13, or maybe as a 9 in Bbmaj13#11 or Bbm13. There are a lot of options so experiment and find which one you like.

In the instance where you have multiple melody notes but don’t want a new chord on every single note, all you have to do is find an accompanying Dorian or Lydian mode which includes all of the notes in question. For example, if the melody goes C D E, well that could be D Dorian, or Bb Lydian, or a number of other options.

I’m a really big fan of this approach and by having a number of these types of chords together, you can create quite a unique sound which feels drastically different to any other technique. You can see elements of this type of harmony throughout the mid 20th century, in artists like Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, and of course Bill Evans. Each of them use it in different ways and in different dosages, but to my ears it always feels fresh. So next time you’re analyzing one of their compositions and run across some weird sets of m11 or maj13#11 chords that don’t quite make sense functionally, it may just be that they are tapping into this modal harmonization technique.

Well that’s it for another newsletter entry. As always, thanks for taking the time to read it and I hope you find modal harmonization as interesting as I do, because lately I’ve been using it in probably a few too many charts! I think I’m going to take a break from harmony related topics next week, but haven’t quite decided on what I want to tackle just yet. So it’ll be a bit of a surprise.

Until next time,

Toshi