(Apr 24 2025) Demystifying The Congas

Recently one of the participants in the Arranging 101 cohort asked me about how to write for congas. As a result, a couple of us spent about 30 minutes discussing the topic in depth after class which made me think some of the readers of this newsletter may enjoy the topic too. For many, including myself, percussion is somewhat of an after thought when it comes to jazz arranging. Like most people who grew up in a Western education system, I was introduced to Latin percussion through the ensembles I played in at school. No one really knew anything about it, including the students who played the instrument, the band directors, and especially not onlooking students like me who played other instruments.

I always loved the sound of percussion though, so inevitably as I formed bands of my own, I would include at least one percussionist. At the time, I knew very little about playing the bass, let alone leading a band and what a percussionist should or shouldn’t do. So I just booked my mates and let them work out what to do. I remember it generally going well but again I was clueless and I doubt it was as smooth as I recall.

As my musical journey progressed, I was eventually given opportunities to write for the Latin Jazz Lab Band at the University of North Texas where I started to see the true limitations of my knowledge. The director, Jose Aponte, pretty much held my hand through the entire process and would tell the percussionists what to play under the charts I brought in. Unfortunately, I missed a fantastic opportunity to ask Jose at the time what he was telling them and how I could replicate that in the music, but I would make up for that later.

Although I was in the presence of someone who really did know something about each percussion instrument, due to my extremely limited knowledge and awareness, I really had no clue just how deep the tradition went for these instruments. To be honest, the same could be said about my thoughts on the more common horn instruments like trumpet and sax too, but that knowledge is far more accessible and I eventually was taught it through the college’s curriculum.

Eventually, I too became one of the band directors who didn’t really know too much about percussion but wanted to include it in my ensembles. I had fooled myself into thinking that I knew enough to really write for the instruments, but after one specific rehearsal when I hosted Jose as a guest artist and he called me out in front of everyone, I had my reality check. At the time it felt terrible but to be honest, I needed the brutal truth and that experience was the catalyst for multiple years of research that has ultimately put me in a much better position.

So what do you need to know to write for congas and not make a fool of yourself like me? Well you need to approach the instrument just like any other. You need to respect that it comes from centuries of tradition that inform how it is played and you need to understand the inner workings of the common techniques used. The latter being considerably easier to grasp than the former.

The congas themselves were created in Cuba in a time where Afro Cuban culture was seen as illegal by the government. The Afro Cubans who created the instruments came from multiple West African backgrounds where one of the core similarities in their music and traditions was the use of three drums (each culture had different names, sizes, and designs but they all had the same purpose musically). Obviously slavery didn’t allow for them to bring any of these drums from their home, so they created new drums out of the resources at hand. Specifically crates used to transport dried codfish as they had the closest sound to the original African drums.

The Afro Cubans would congregate and play music regularly due to the Spanish allowing for a weekly day of rest for the slaves. It was in these informal gatherings where the cultures of several West African nations blended together and eventually created what is now thought of as Rumba. As such, the rhythms most strongly associated with the congas are drawn from the various Afro Cuban folkloric religions such as Palo, Santeria, Vodu and more. Originally there would have been three different musicians, each being assigned a different sized drum and a specific rhythm for a given song. However, as the music developed, the role of these three drummers has now been boiled into just one player who plays multiple congas at once (in traditional settings they still maintain three drummers but I’m mainly referring to commercial and Latin Jazz ensembles).

To complicate the situation a little more, from the mid 19th century through to the mid 20th century, dozens of new styles were being developed across Cuba, the most notable being Son (the style which introduced the world to the montuno). As the styles expanded across the island, they merged with each other to create a pretty awesome combination of rhythms and musical characteristics. Although Son originally didn’t include congas, through artists such as Arsenio Rodriguez they were integrated into the style and picked up new vocabulary based on the other instruments commonly used in the style.

So why is all of this important to know? Well the history of the congas informs why they play the rhythms they currently play. Depending on the style, there may be dozens of different “correct” options for a conguero to choose from and as a writer looking to include congas in your ensemble, you should try to be aware of them. Think of it like this, how many different grooves exist for the drum set? Now think about how many different ways you can play just one of those grooves (eg. Elvin Jones vs Tony Williams vs Buddy Rich etc. on a medium swing pattern)? That level of complexity exists for each of the Latin percussion instruments too but for their specific styles. It is definitely okay not to know much about congas, but we need to respect the instrument and the musicians who play them so that we can accommodate them better in our arrangements.

As you can see, there’s a lot to unpack in order to understand how to write for congas and far more than I could include in a single newsletter entry, let alone a dozen. However, I will unpack the common hand techniques used on the instrument so you can go away and at least start identifying them in the music you listen to. They include:

Bass tone (Open/Closed): A bass tone is when you strike the center of the drum head with the palm of your hand. It gives the lowest tone available for the drum and often congueros will tilt the conga so that these tones can be more resonant. There are two variations of the bass tone, an open strike, when you let the hand rebound letting the tone resonate, and a closed strike, when the hand stays in contact with the drum head. Typically this is notated by the letter B above a given rhythm/note.

Open Tone: An open tone is when you strike the edge/rim of the drum head with your palm (just under the knuckle line) and let the hand rebound. It produces a higher pitched tone and is more accessible at faster tempos compared to the bass tone. Typically this is notated by the letter O above a given rhythm/note.

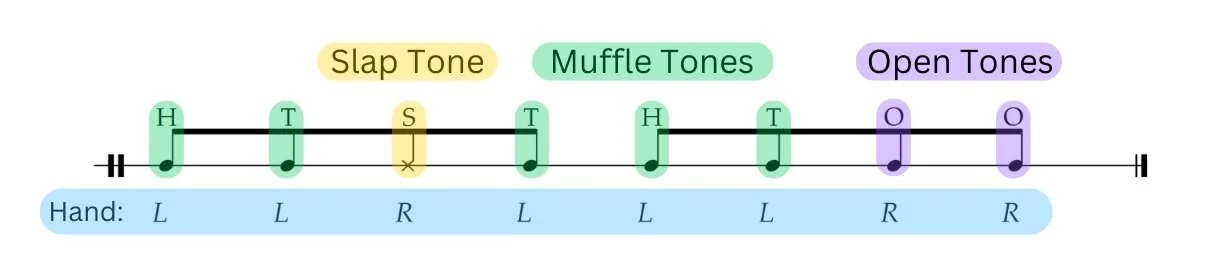

Slap Tone (Open/Closed): A slap tone is one of the most iconic sounds on a conga but also the most difficult technique to pull off. It is created with a similar hand shape to the open tone but a different part of the hand actually strikes the edge/rim of the drum head. It’s slightly different for every hand shape, but personally I’ve found that if I slightly spread my fingers and try to focus on making contact with the stretch of skin between the bottom of my ring finger and the first knuckle, it produces a great slap sound without having to use a lot of force. Similar to the bass tone, there are two variations with the open slap being when you let the hand rebound from the skin (in my opinion the hardest to execute well), and the closed slap being when the hand stays in contact with the skin. Typically this is notated by the letter S above a given rhythm/note and I personally also use a cross notehead.

Muffle/Mute Tone: Last but not least is the muffle tone which is an indistinct strike on the conga which is meant to be felt more than heard. There are two main types of muffle tones, those that occur on the rim/edge of the drum head, and those that occur on the center of the drum head. The rim variation is quite similar to an open tone except you don’t let the hand rebound, resulting in a muted strike with no resonant tone. The center variation starts off exactly like a closed bass tone but then alternates with a fingertip strike. The motion comes from the wrist and can be easily understood by putting your hand face down on a flat surface and then just lifting up the fingers while the palm stays fixed and then letting the fingers fall back to the surface. Commonly this type of muffled tone is thought of as a heel and toe movement, and the closed bass tone is notated by an H above a given rhythm/note while the fingertip strike is notated by a T.

One thing you should be aware of is that many professional conga players don’t read music notation as Afro Caribbean music is primarily passed down orally. Unfortunately a byproduct of this is the lack of a standardized notation system for the instrument. I’ve seen a lot of different conga parts over the years and none of them have looked similar. To keep things simple, all I will suggest is to notate the rhythms clearly, specify which hand technique you want for each rhythm, and if you want multiple congas to be used, have a different note assigned to each drum. As you get more familiar with the common patterns, you’ll see the normal conventions for each hand technique and how they work together. I’m still blown away by watching modern congueros at work, and the more I learn about the instrument, the more I realize just how exceptional musicians like Pedrito Martinez really are.

Well I wasn’t expecting this to be such a long entry but here we are. I always figure it’s better to go a bit over than not explain things fully, and with the incredible history and culture that the congas are a part of, I definitely was trying to restrain myself from writing what would’ve been a short novel on the instrument this week. Thanks for reading this far and always feel free to reach out if you have any questions.

Until next time,

Toshi