(Nov 24 2025) How Jazz Harmony Changed Throughout The 20th Century

Well I failed. I wanted to try and maintain a weekly newsletter entry but for the last few months I’ve been buried by research, spending excess amounts of hours trying to zero in on the early traditions of jazz arranging and exactly how it evolved over the 20th century. For what has seemed like an eternity, I’ve been reading dozens of books, articles, and getting my hands dirty with original scores by the likes of everyone from Duke Ellington to Gil Evans, and even some less remembered names like Eddie Sauter and John Bartee. However, on the flip side, my research has yielded a variety of new topics for me to write about and with some luck I might be able to stick to something of a regular schedule at least for the next few weeks.

One such area which I’ve been deeply fascinated about is the progression of jazz harmony, specifically at what points certain techniques became commonplace and why. In my own arranging journey, somewhere along the way I started to feel like I had a solid grasp of which time periods were associated with certain sounds. Most likely due to going through an undergraduate jazz degree and picking up bits and pieces along the way. However, after spending a little too long dissecting scores lately as well as listening to an absurd amount of recordings which no one has likely heard for half a century or more, I started to realize my whole idea of jazz harmony was considerably different from what really took place in the 20th century.

Prior to this year, my main impression was that bebop was the quintessential moment when jazz harmony shifted from more straight forward chord changes to what we see today. But the more I looked through the music of the 20s and 30s, the more I was shocked to see that extensions and alterations have been baked into the harmonic infrastructure of jazz since at least the mid 1920s. Even ideas such as tritone substitution make an appearance in scores well before the time of Dizzy and Bird. What I realized is that while bebop may have been a critical point in the development of jazz improvisation, many of the harmonic techniques associated with the style actually had been utilized by writers for years prior to the 1940s.

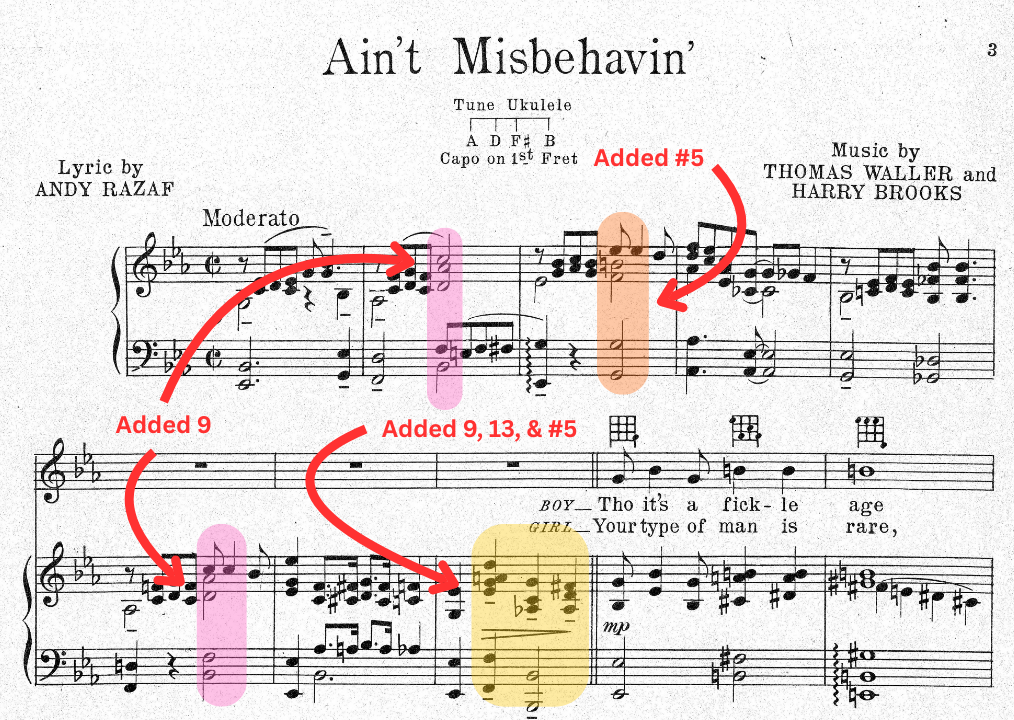

Now we all know that jazz harmony has often been linked with the classical trends of 19th and 20th century contemporary composers such as Ravel, Stravinsky and so on, but the connection to those sounds was also evident in the many thousands of published pieces through Tin Pan Alley. So even though someone like Ellington may have been influenced by the innovations of the classical world, so were the many writers behind the sound of early American popular music. While the original scores of Jerome Kern or Cole Porter may not have used the chord symbol conventions we currently utilize, a quick look at many of their scores showcase voicings which highlight color tones.

This particular example is dated from the 1920s and very much went on to be arranged by popular bands of the day such as those led by Fletcher Henderson. So while the big band tradition was starting to grow out of the hot jazz influence of New Orleans and Chicago, the pop music they were basing their arrangements off already provided a layer of color without the need for further innovation, well at least to begin with.

After looking at many of the charts from the early big band era, it is clear that extensions and alterations littered the horn and piano voicings. But perhaps not to the degree that we might be familiar with in later works by those such as Sammy Nestico or Thad Jones. Instead, most of the color tones were derived purely from the notes naturally found in a major scale. As a result, the music still preserved a diatonic sound. But like most things, the music of the late 20s and early 30s was filled with exceptions, one of which was the obsession with the whole tone scale. For one reason or another, the American public fell in love with the scale and in a majority of compositions from the time you’ll find small whole tone passages which feel somewhat alien to the rest of the piece. This also led to the heavy usage of the augmented 5th, the first alteration outside of the diatonically occurring diminished sound, to enter jazz.

So in the late 20s there were already many different colors being utilized in jazz harmony. Coming from the world of American popular music you had diatonic extensions and alterations such as the 9th and 13th as well as the use of augmented and diminished triads to create a level of chromaticism. As music progressed, new approaches began to be integrated, namely the use of chromatic approach chords. What we see somewhere in the early 30s, or perhaps even earlier, is that dominant chords begin to be used to resolve chromatically into one another. For example the progression A7 - Ab7 - G7. From what I can tell this wasn’t associated with the name “tritone substitution” at the time, but as we can tell today, it gives the same sound. The main difference between the approaches though is that this sort of sound was only used with a string of dominant chords that eventually resolved to the V rather than any sort of bII sound.

As you can imagine, before long composers started to draw from the sounds of the minor scale, picking up the half diminished ii chord and the minor iv. Interestingly, extensions still were primarily drawn from major keys more so than those found in minor keys, most likely due to the extra dissonance they introduced to the music. This is however, where bebop starts to play a role in the development of jazz harmony. Thanks to the music of Art Tatum, Duke Ellington, and many others, harmony took a sharp turn into chromaticism, picking up flavors that were once seen as either problematic or had simply not been popularized yet. There was also the utilization of more chromatic vocabulary in improvisation, now adding tones such as the b9 and b6/b13 into the mix through various justifications. The result was a harmonic world where it was common for chords to have extensions and alterations drawn from places other than the major scale, purely for the purpose of creating chromatic resolutions. Tritone substitution became commonplace as well as techniques like side-stepping, which added a level of non-functional harmony into progressions that only made sense due to how certain chord tones were resolved. While I had once believed bebop was the jumping off point for extensions, what I discovered on my journey was that it really was the turning point for chromaticism, where a younger generation of musicians

For the bulk of the 50s, jazz harmony stayed stagnant, mainly following the conventions established by bebop. Of course through writers such as Gerry Mulligan, John Lewis, and Gil Evans, there were definite forays into non-tonal areas, but these weren’t captured by the masses. Instead it was only when hardbop finally started exhausting the chromatic possibilities of bebop, that jazz once again shifted. This time it pushed the boundaries much further, moving in three different directions. On one side you have the creation of modal jazz, where instead of following functionality, chord progressions now focus on exploring the sound of a given scale or mode that best connects with a given chord. The second direction was through free jazz, where all chords and notes were seen as equal and it was up to the interpretation of the individual as to how they wanted to play them. Finally, the last direction was through a progression of hardbop into a more modern form of the style I like to refer to as postbop. In this period musicians such as Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock broke away from tonality and used a mesh of various non-functional techniques alongside standard conventions to create a new harmonic vocabulary.

Now unfortunately there are far too many techniques to cover when it comes to these three directions and trying to unpack them. But the result of all of them created a sense of harmonic ambiguity in jazz, whether that be through using slash chords, new substitution techniques, or highlighting modal chord changes. I have however written a full resource on the topic which you can check out over on my website at https://www.toshiclinchproductions.com/postbop.

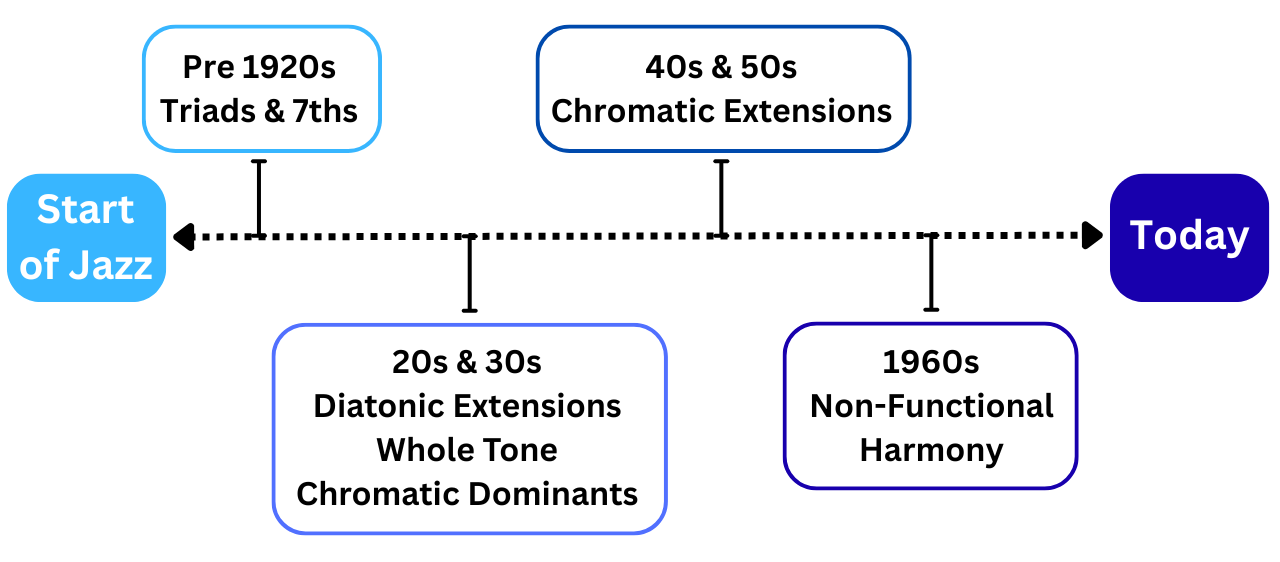

Interestingly, after the 60s, jazz harmony didn't progress to that many more unconventional locations, with only one or two sounds emerging. All of the specific techniques followed in line with the explorations of what had been previously established with the main shift taking place in other areas. To help summarize the progress of each period in jazz history I’ve created a graphic below which should hopefully help differentiate the various harmonic approaches.

Well it’s good to be back and hopefully you’ve found this entry somewhat interesting. If this is the sort of content you like, then you may like the two dozen or so resources I’ve written on my website which cover a wide variety of styles and arranging techniques. They are all free to access and I generally add a couple every 6 months or so. You can find them here - https://www.toshiclinchproductions.com/arranging-resources

Over the next few days it’s Thanksgiving up here in the US. So for those of you who are celebrating the holiday, I hope you have a wonderful time filled with great moments with those close to you. I’ll try my best to stick to somewhat of a regular schedule with these but what I’ve realized is that I want to use this medium to talk about fun different arranging topics, some of which may take me longer to write or research. Also, as this newsletter is purely a creative outlet for me, at times it may not be prioritized to the same degree as other outlets. With all that said, this was a fun entry to write and I’ve been thoroughly enjoying submerging myself in the history of arranging so I hope this has brought some level of enjoyment to you too.

Until next time,

Toshi