How To Lead & Conduct

Your Big Band Effectively

Leading an ensemble for the first time may be one of the most daunting musical experiences in anyone’s musical journey. Like anything in life, it takes a lot of repetitions before you start to feel comfortable standing in front of others and being able to instruct them without the fear of judgement. Personally, it took me years before directing a rehearsal, running a workshop, or leading a band through a performance felt normal, and unless you’re one of the lucky few, for most people this seems to be the common experience.

My first foray into band leading started out in high school when me and a group of friends decided to run a jazz combo together. We each shared the responsibility for leading the band which helped us start to see what actually goes on behind the scenes when it comes to organizing rehearsals and performances. It was a great introduction to the role and there was very little pressure to get it right as we were likeminded friends who all had no experience. As I transitioned into university, I kept running similar bands with my close friends. Over time I became more of the designated leader but for the most part the ensembles were still run in a pretty open capacity which allowed everyone to speak up and make suggestions. It wasn’t until 2016 when I decided to take the plunge and run a big band for the first time.

Unlike my other experiences, when I put my first big band together I assembled as many of the best players at the university that would say yes. I was surprised how many agreed to join in, which only amped up my sense of imposter syndrome. I still remember the first rehearsal as if it were yesterday. I had no clue how to conduct a band (I had done a classical conducting class but that wasn’t too applicable to directing a big band as we will cover later), I had very little knowledge when it came to the big band tradition especially outside of playing bass in that sort of ensemble, and I was surrounded by a lot of very talented people who were colleagues but I didn’t really know that well. To my surprise, everything went smoothly and all of the moments I was dreading never really felt bad when they arose. The band had enough collective experience that when I didn’t know something, they could help each other out and were happy to be patient with me. What I learnt was that most people actually are quite sympathetic toward conductors, especially when they are just starting out, and because everyone wants the music to be as good as possible, often the band members will pick up the slack when needed.

While I learnt a whole lot about leading a big band during that first experience, unfortunately it only really lasted an intense week or two. Very quickly most of the members graduated and we all went our separate ways. Eventually I ended up back in Australia where I was quickly faced with my next encounter with conducting a big band, this time a paid opportunity to workshop with a school band run by a high school friend of mine. Funnily enough, I actually almost forgot about the workshop entirely as it took place a day after I got engaged and I only realized the morning of! Fortunately, even though it was a 4-5 hour drive away, I made it just in time.

Interestingly, this second major experience leading a band was completely different to the first. I was coming in unaware of the music they were playing, still had very little experience directing a band, and I was now surrounded by school students who lacked the level of experience I had relied on previously. Somehow I convinced them all that I knew my stuff, but the entire time I couldn’t believe anyone would pay me to come and direct a band. I don’t think I made a fool of myself, but I definitely didn’t feel comfortable and was very aware of everything during the entire 3 or so hour workshop.

Somehow by going to a university with such a strong association with big band jazz, people back home in Melbourne started to think I had some magical conducting knowledge they didn’t. Ironically, I don’t think I knew much at all and while studying I spent most of my time focused on arranging more than any other skill. A few months went by after the first workshop, and then I was booked to direct a youth ensemble for a month or two. Only having had two short experiences conducting a big band, I still felt extremely anxious about the role but I agreed to it anyway.

Stepping into that band was a whirlwind. It was filled with the brightest local musicians of their age and they all looked at me hungrily wanting to absorb everything I had to say. The project also featured a number of brand new arrangements someone had recently written for the band, meaning no one had played or heard the music before and I somehow had to make it come together over five rehearsals. I decided to take a throw-everything-at-the-fan approach and would just see what worked and what didn’t. Somehow we all made it through pretty unscathed, and I had convinced the director of the program that I was good enough to be booked for the next project. However, that was more likely because he had been doing some rather inappropriate things at his school teaching job and may have wanted to avoid any unnecessary heat elsewhere (he was eventually caught and prosecuted). Either way, it meant I now had another fiveish weeks to continue working with the band for their next project.

The second project was more of the same but what I didn’t realize was that it was the first time in my life that I was able to have consistent repetitions directing a band. Over the course of a couple of months, I had more confidence and less self doubt, and it helped knowing that the students didn’t know how little experience I had. Eventually the bad behavior of the person previously mentioned caught up to him which led me to take over the whole youth program operation. What that meant for my conducting journey was that I now had two big bands under my direction that could rehearse and perform as much as I wanted. I decided to lean into the opportunity and continued the momentum I had built.

Without going into too much more detail about the youth program, I spent the entirety of 2019 working on my conducting skills. By running the program, I had the ability to bring out a number of international artists who I was able to learn from purely by watching how they directed the ensembles. Alongside the youth program, I also decided to run a number of other ensembles, and for the full year my average week included 3-5 performances I produced, arranged, and directed, as well as at least 4 three hour rehearsals I had to conduct too. It was a lot of work but my comfort with leading a band skyrocketed and by the start of 2020 I felt comfortable stretching myself once again and decided to put on the biggest concert I had ever produced at the time.

Similar to that first experience leading a big band back in college, I went all out and decided to assemble the best players Australia had to offer. Only this time I had the extra pressure of working out the finances, copyright, writing/transcribing the charts and playing in the band. Something I’ve since decided is far too much work for one person to handle when dealing with large performances. Just like the first time I walked into that conducting role with my peers at university, when I entered the rehearsal room for this concert I was filled with that same feeling of dread and imposter syndrome. But just like my first experience, the professionals picked up my slack and rallied to make it a huge success, one which I decided to professionally film and record and can be viewed on the TCP YouTube channel.

After the various COVID related lockdowns in 2020/21 I resumed my youth program and normal ensembles but had a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity land on my doorstep. After one of my various big band shows at a local club, one of the patrons was a choir director at Melbourne University and asked if I would like to produce a concert dedicated to Duke Ellington’s Sacred Concerts with a full choir in the largest cathedral in Australia. As you might expect, I immediately accepted. However, this time something felt different. I had changed, and for the first time ever, I felt comfortable with getting in front of the ensemble even though the stakes were the highest they had ever been in my career.

I compiled an ensemble which represented all parts of my conducting journey. I flew in friends who had been in my first big band, there were alumni of my youth program, and a number of hired guns who I was genuinely surprised they accepted the gig because of their status among the Australian jazz scene. I came into the first rehearsal guns blazing, and by the time the final note was played at the concert, it felt like the ultimate way to celebrate my entire journey. And at no time did I feel uncomfortable directing the band. Sometime in 2022, I must’ve crossed the ~10,000 hour mark, or however long the necessary amount of time needed to stop doubting yourself and feel confident in your abilities. I have no clue when it happened, but I do know that it took the better part of a decade and thousands of conducting opportunities before I finally had that feeling.

Now you might be thinking, why the hell has Toshi spent so much time telling us about his conducting journey and how is this relevant? Well the main reason is that it helps show you how I got to where I am today and how it felt like going through the process. It also demonstrates the sheer amount of time needed (well at least in my case) to start feeling some level of comfort with standing in front of a big band and feeling worthy of directing them. There’s nothing special about me, all I did was throw myself at each opportunity and learn from my mistakes. I listened to as much advice as I could along the way, and pushed my boundaries where possible. In total, it took me close to 7 years before I lost the sense of imposter syndrome, and that’s not to say it won’t come back if I decide to delve into other arenas like conducting for orchestra or in non-jazz settings.

On this page I’ve compiled as much as possible about what I’ve learnt from my experiences. This is the sort of knowledge that has come from the trenches through hands-on work and isn’t what they usually tell you in your average conducting class. Of course there's more than one way to go about directing a big band, but this is what has worked for me and hopefully it will be of some help to whatever situation you might be going through. I’ve tried to divide the resource into a number of different sections, focusing on various elements that I wish I would’ve known when I started my journey. These include how to actually conduct a big band all the way to more general points on what makes a good bandleader. While I would still consider myself in the early phase of my conducting journey, I’ve been lucky enough to go through a lot of experiences in a short amount of time and have learned a lot. It’s my hope that this will at least help you save a bit of time with your own journey and that you’ll be able to avoid some of the mistakes that I’ve made. With that said, I’ve spent way too long on this first section and it’s time to jump into some actually practical skills!

Conducting Basics

Before stepping in front of a band, it may be a good idea to brush up on some conducting skills and understand how directing a big band differs from other conventional ensembles like wind bands and orchestras. As there’s a lot that can be said about the art of conducting, enough to satisfy an entire career in fact, I’ll keep this section brief and only highlight the areas I’ve found useful in a big band setting. Just know that this is only scratching the surface and if you find this interesting, then there’s a whole world out there for you to dive into.

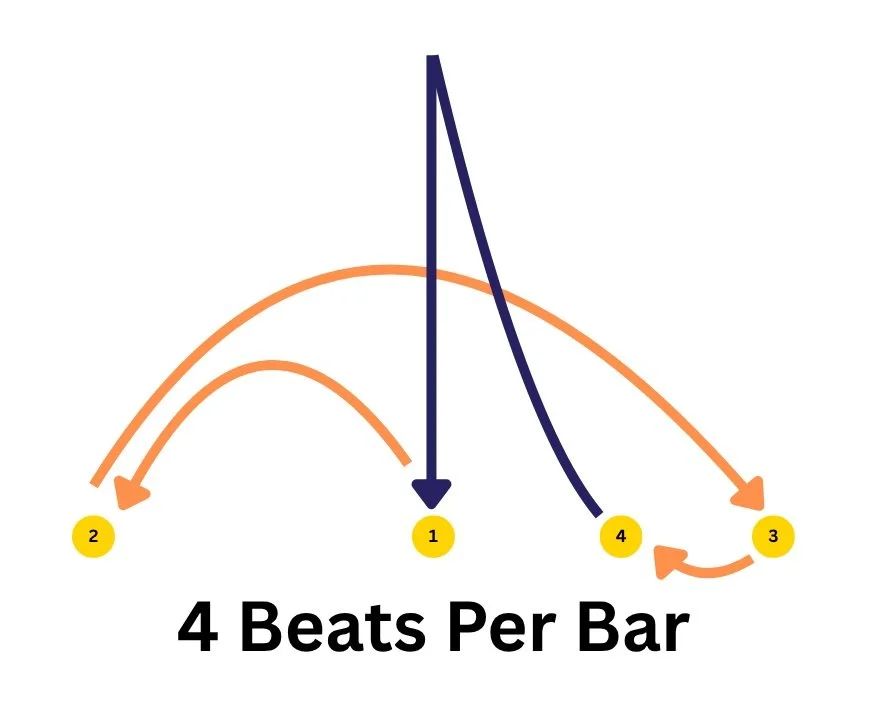

A great place to start is understanding how to conduct various time signatures. There are four main hand movements and you simply add or remove strokes based on the meter you are in (see graphics below). The most important part though is that you have a good ictus, a fancy word which means the imaginary point in the air at which you stop your hand motion to indicate the beat. While most jazz musicians won’t care if your hand movements are unconventional and whether you follow standard conducting patterns, they will need a clear sense of tempo from your movements. In theory this is quite easy to execute, but to give a fixed ictus while also thinking about everything else going on can be challenging. What has worked for me in the past is to practice my conducting at a waist high table where I let the surface of the table dictate my ictus. That way I get used to a fixed point of contact with the beat which can then be practiced away from the table.

Don’t worry too much if you mess up the conducting patterns, it’s pretty rare to see anyone conduct “properly” when standing in front of a big band. Initially, I leaned into using them a lot as that was all I knew but as I got more confident I realized that the rhythm section really does a lot of the work with keeping time. As they establish a consistent pulse (in most cases), it is far more important that you focus your conducting efforts on entries, cut offs, volume/balance, and maintaining the tempo. For the most part, formal conducting patterns can demonstrate all of these areas but to do so requires a significant amount of skill and practice. Instead there are pretty easy work around’s that you can jump into doing straight away and get the job done just as well.

Keeping Time

One of the simplest yet most effective ways to maintain tempo is to tap your hand on your chest. The gesture itself is quite visible and conveys the pulse you want out of the ensemble while also being hidden from the audience. In situations where the ensemble is not following, you can upgrade to more audible and exaggerated gestures such as snapping your fingers or clapping. Within a big band there is one player who can broadcast the tempo more so than any other instrument and that is the drums. Due to the nature of the instrument and their role within a big band, if you are finding that the ensemble is unresponsive to your time keeping, then make sure you have good communication with the drums as they will be able to help you steer the ship to safety. Of course it is everyone’s responsibility to keep good time, but it will never hurt having the rhythm section instruments on your side first when trouble arises.

For the most part, you probably won’t have to keep time as a conductor. Personally I only do it when the band feels unsteady or is quite obviously rushing or dragging. If you have a set of great players, you’ll likely find yourself focusing on other areas. All too often new conductors think it is vital to keep conducting tempo throughout a piece but as soon as you realize it may not be necessary, it frees you up to focus on getting the most music out of the ensemble. Other than course correcting, the only other times I conduct strict time are in odd meters (specifically focusing on giving the ensemble downbeats), rubato sections, or when there is no fixed time coming from the rhythm section. In any of these moments my main priority is to make sure the ensemble can follow my pulse and that I am being as clear as possible.

Cues

Once you’ve dealt with time keeping, the next major job of a conductor is to signal the entries of instruments and sections. Regardless of what you do with your hands, the easiest way of doing this is to get used to making eye contact with the musicians. As soon as you lock eyes with a musician, it gives a sense of reassurance that you are with them in the moment and that you’ll come out of it together. You can then focus on what to do with your hands.

Honestly, cues can feel pretty awkward at the best of times. The only one which feels solid is a downbeat entry on beat 1 as it lines up with common conducting patterns, but as I’m sure you are aware, there are more than just one type of entry that exists. The key to a convincing cue is to make sure your hand/arm movements are very obviously signalling an entry, and while you may think you’re doing a good job, the real test is how accurately the musicians can interpret your gestures. In a professional setting, cues are pretty much only cautionary and almost all pro musicians pay enough attention that they know where they are in the music without a conductor. However, if you work with amateurs, enthusiasts, or people that are simply learning how to play, often there is more dependence on the conductor to ensure a correct entry. It is in these environments where your cues carry more weight and there is more responsibility for you to get it right.

For me, I only started feeling confident with cues once I stopped trying to conduct tempo all of the time. By giving myself the freedom to use my hands more creatively, I allowed myself the space to actually develop various conducting techniques which were simply too hard to do due to my inability to multitask. I realize that in some settings this is simply not possible, such as more traditional ensemble settings like wind bands and orchestras where the conductor is often the only steady pulse within a piece. However, I was lucky that the music I was conducting my big band through gave me that freedom and eventually I was able to merge the two together and successfully cue and conduct tempo at the same time.

What I realized is that most jazz musicians just need a clear down stroke (similar to conducting a beat 1 normally) in order to know exactly where their entry is, regardless of whether the entry begins on or off the beat. For example, if the entry is coming in on beat 3, simply reset your hand pattern by giving a clear upward motion the beat prior and then giving a downward motion on beat 3. Most musicians respond to the direct nature of a downward conducting motion and it is quite clear that it means something significant is happening in the music. In general, I will only do this with one hand most of the time, and reserve using two hands only when emphasis is needed (I only really use two hands for signposting, but more on that shortly).

When there is an entry that starts on an off beat, surprisingly strong downbeat cues work effectively too. Trying to accurately cue a swung eighth note is quite silly and often conveys confusion. Fortunately, almost all musicians are smart enough to realize that your big cue on beat 3 was actually to give them a jumping off point for their and-of-3 entry. If you want to go slightly further, you can give a pretty strict upbeat directly after the cue which may help indicate more accurately the offbeat entry, however this requires a pretty strict upward ictus that correlates with the music. Another option is to get both hands involved and have your less dominant hand cue the downbeat with your dominant hand hitting the offbeat entry. This gives the best of both worlds and when I use this particular technique I give a conventional downbeat with my left hand while either using another strong downward motion on the offbeat, or sometimes just pointing (can be good to very clearly indicate the instrument/s entering) with my right hand.

Everyone has a different way of going about cueing and you may also change your approach depending on the ensemble you are directing. There’s no right or wrong way, simply approaches that are effective or not. Unfortunately, depending on who you’re working with and how well they can interpret your gestures will ultimately dictate the success of your cueing, more so than the actual movements you choose to use.

Cut Offs & Fermatas

On the other side of the equation are cut offs. Generally speaking, most cut offs are simply a discussion that needs to be had in rehearsals, with musicians deciding exactly how long they should hold a note for. However, the main time you need to be aware of how to signal a cut off as a conductor is when there is a fermata.

Back when I took a classical conducting course at university, they gave a number of different approaches to dealing with fermatas, all of which have faded with time and never really seemed to work when I stood in front of a big band. What I’ve since learned through trial and error is that there are three crucial gestures you need to give during a fermata. The first is the entry, the second is making sure it is clear you are still holding a note, and the third is when the note is meant to stop. The entry is pretty straight forward, it’s just a cue and should be treated as we have previously discussed. The hold is also relatively straight forward, you simply maintain the position of impact from your cue until you are ready for the cut off. Finally, the last part is when things get unnecessarily difficult.

We’ve all been in a band where someone has tried to cut off the last note of a piece only for the band to be divided on where the exact cut off should happen. Unfortunately, the end result is that the music suffers and it sounds untidy. Why does this happen? Everyone usually says it was due to a bad cut off by the conductor/individual in question but not go any further than that. Well the reason the cut off was problematic is because it was unclear. More specifically, the person was unable to indicate the exact point that they wanted the note to end. What this looks like in reality, is that people give a downbeat or some weird hand gesture (for some reason people love throwing out whatever they think might work when they are asked to give a cut off) but it has no ictus or fixed point. So many people try to think of a cut off in a similar way as a cue, which in the classical world is often how it is treated, and as they don’t realize they need a very precise ictus for that sort of gesture to be successful, the performance is compromised. Fortunately, we live in the big band world where there are no set rules for conducting and we can use any techniques as long as they signal our intentions more clearly.

What I’ve found to be quite successful is to use a motion which starts with an upward facing open hand and then quickly turns into a closed fist. As there is a clear point where the hand closes into the fist, the band is able to precisely realize where the end of the note should be. No strict rebounds or big downbeats necessary, just a simple closing of a hand. Since realizing how effective this type of cut off is, it has been my go to gesture for all cut offs that have to be conducted.

Signposting

Unlike cues and cut offs, signposting operates a little differently as its main function is to communicate where an ensemble is within the music. This can look like signalling double bar lines, rehearsal marks, bar numbers, repeats, and really anything else that impacts the form of a piece. As with all the other gestures we’ve looked at, the better the musicians you are dealing with, the less likely they’ll need you to spend time accurately signposting through a score. However, it is never a bad thing to do as it will always reassure musicians and help everyone maintain a certain level of confidence with a performance. To demonstrate how crucial signposting can be, there is one specific trainwreck I experienced that could’ve been fixed if the conductor had correctly communicated the sections with the band.

While I was running my youth program back in 2022, I tried to expand the business and ended up taking on a couple of different composers to run the ensembles. Everything was generally going fine until one specific performance of Stan Kenton’s Cuban Fire suite. Due to a number of issues, the band started getting lost in the music, so much so that the performance turned into the biggest musical disaster I’ve ever witnessed. As a bystander, I had no control over the situation and could only watch as the band kept getting further and further away from one another and the director simply just stood there and conducted time. There was no indication as to where in the music the band was and no attempt at trying to bring the ship back on track. As the band had successfully performed the music earlier that same week under a different director, it was clear that the musicians could make it through everything when guided, but the absence of any sort of signposting ended up leading to a complete trainwreck.

Ironically, signposting isn’t all that difficult, it just requires concentration and remembering the moments that it’s needed. I make use of two different sorts of gestures, some which come from traditional conducting and others that come from common hand shapes. It all depends on what exactly I’m trying to convey to the ensemble. For rehearsal marks and double bar lines I give a normal downbeat gesture, however I make sure to over emphasize it with both hands. Usually I only use one hand for cues or keeping time, so by using both hands it helps show the significance of the gesture. Sometimes I’ll break from this when I want to very clearly point out which rehearsal figure we are coming up to by mouthing the specific figure/bar number and then trying to represent it as best as possible with my hands. For example, let’s say I was coming into the A section, I could mouth the letter A and then try to make an A out of my two hands. This works particularly well when someone might be lost as there is no doubt which section we are about to enter.

This sort of “unconventional” conducting also plays into common hand signals that big bands use in repeated sections. As many of us have experienced, repeats can be confusing and it is easy to be uncertain how many times a section is being repeated and when you’re meant to go on. As a result, most jazz musicians use three specific signals:

Open Repeat: Making an “O” with your hands

Last Time: A closed fist

Going On: Either pointing to the side or by making a 90 degree angle with your palm and fingers and then moving your wrist back and forth (think of it as the reverse of the “come here” hand gesture)

Conveying Intention

A big part of conducting is being able to bring the music on the page into reality. Later on we’ll look at how to interpret a score but a large part of the process also comes down to how you communicate the music through conducting. So far we’ve focused on mechanical techniques which are required to make the music operate but they actually do nothing to convey any emotion. And while they are essential from a conducting standpoint, it’s really how you go about pulling the music out of a score and getting an ensemble to play it which is the best part of directing a big band. Unfortunately, so many people who stand in front of a band never get to experience this because they don’t feel comfortable or they don’t realize how much they can actually put their spin on the repertoire.

Once you understand what you want the band to do, e.g. get louder, you then need to be able to broadcast that intention to the players. The primary way we can do this as conductors is to physically represent the music by how we move our entire body. At first, this can feel pretty unnatural depending on what you are trying to convey. Most people are pretty shy, but as the leader of the ensemble you need to try and step out of your comfort zone so that the musicians can see exactly what you want them to do. There are many wonderful examples of this from the classical world with two of my favorites being Leonard Bernstein and Gustavo Dudamel. No matter what clip you find of them online, you’ll see that it is extremely clear what they want out of the orchestra purely from their body movements. Dudamel even goes a step further by making use of his long hair which helps add some drama into his more serious and sharp movements.

I've always found in my own conducting that exaggeration helps ensembles understand my intention. I make my gestures very large and stretch out and use my entire wingspan when I want the band to have a louder volume, whereas I’ll almost hunch down and use quite small arm movements when I want it to be quiet. If the band still doesn’t respond I then make it even more obvious by literally waving my arms upward so they can see I want them to get louder, or the opposite to be quieter. In extreme cases I’ll even verbally say what I want and have done so in performances, but only when absolutely necessary.

In the past I’ve heard various opinions on how flamboyant you should be with your conducting gestures with some respectable individuals saying that big band conducting should be done subtly or discreetly. Personally I disagree and if a band isn’t performing how you’d like then you should try over exaggerated movements to see if they respond. However, I do understand that everyone is different and there are multiple ways of approaching the topic which yield positive results. Find what works for you and keep doing it.

Outside of dynamics, you can affect a band’s time feel by how rigid you make your movements. If you want it to feel floaty then you can use more fluid gestures, whereas if you want strict time then everything can be portrayed quite mechanically. Every musical situation is unique with some circumstances such as rubato sections needing more relaxed and flowing gestures while intricate 16th note funk requires more fixed movements.

How Much To Conduct

Now that we’ve covered the basics of conducting, the hardest decision is knowing exactly how much you should be doing while standing in front of a big band. Unfortunately every context is different and how much may be required varies from band to band and piece to piece. If you opt on the side of over-conducting, often no real problems will arise, you may just feel that some of your gestures are unnecessary and there is a chance that musicians may get confused by the amount of information you’re trying to convey. On the other hand, under-conducting may lead to the opposite where the players don’t nail their entries and simply just read the ink without making the most of the music.

All I can suggest is to try and be aware of what is going on in the ensemble. Use your eyes and ears to see how people are reacting (or not reacting) to your conducting and adjust accordingly. That means not burying your head in the score at all times. You also can ask the players for feedback if you’re in a rehearsal or at a set break, and where possible you can adapt to what they are saying.

Remember that there are no real established rules when it comes to jazz conducting. Through repetition you’ll find out what works for you and as a result you’ll bring a little piece of yourself into your gestures. When you’re just starting out, try to get better at one gesture at a time until you feel comfortable with it. Perhaps that’s keeping time or cueing entries, it doesn’t really matter, you’ll work out pretty quickly what is most important for your situation. Once you feel confident, try to multitask with one hand being assigned to a gesture with the other doing something completely different. For example, cueing a section while keeping time or perhaps flipping a page in the score. This will take a bit more time to develop but isn’t too difficult. I mean if I can do it, anyone can.

Interpreting The Score

The other side of conducting is understanding how to interpret the music written in a score. Oftentimes there is a feeling that you need to make sure you perform the music as the composer intended but almost always you will be dealing with musicians that come from a different period of time with different lived experiences so it may literally be impossible to recreate the original intention no matter how hard you try. With this in mind, my approach is to follow your gut and make whatever band you are directing sound as good as they can, which may in fact mean changing the music written in a score.

There are many ways you can practically express the music in a score but most of it is hidden unless you know what you’re looking for. I don’t mean following clearly marked dynamics or other types of text, I mean looking beyond those to see how you can craft emotion out of the notes written. Practically this can be done by understanding the big picture of a score, knowing where the music is leading to are coming away from, what sort of articulations may help emphasize a given moment, and other considerations such as the hierarchy of passages. There really is no limit to how much you can pull from a score but you have to be courageous enough to experiment and also be humble enough to listen to the music the composer originally wrote. Somewhere between those two extremes you’ll find the sweet spot. Don’t worry I’m not going to leave you there, let’s dive into how to practically do this.

Direction & Contour

When most people look at a phrase they only see a grouping of notes. Perhaps there may be a dynamic given but in most cases they simply do the bare minimum and read the notes and that’s it. However, every line has the chance to be expressive and the easiest way to access that expression is by thinking about phrases having direction. There are three primary directions a phrase could take, they could be building into something, coming away from somewhere, or maintaining some sort of neutral ground. In most cases when musicians are unaware of direction they simply play music neutrally but that doesn’t have to be the case.

If you are unsure of what sort of direction a given phrase has, experiment. What I’ve found is that almost always when the contour of a line goes upward, it feels great to build dynamically, and the same can be said for the opposite too. It’s much more rare for music to feel good when it is stagnant but there are still many examples that can be drawn upon where a neutral approach is beneficial. The most important part though is that you are aware of how you want a given line to be interpreted at all times.

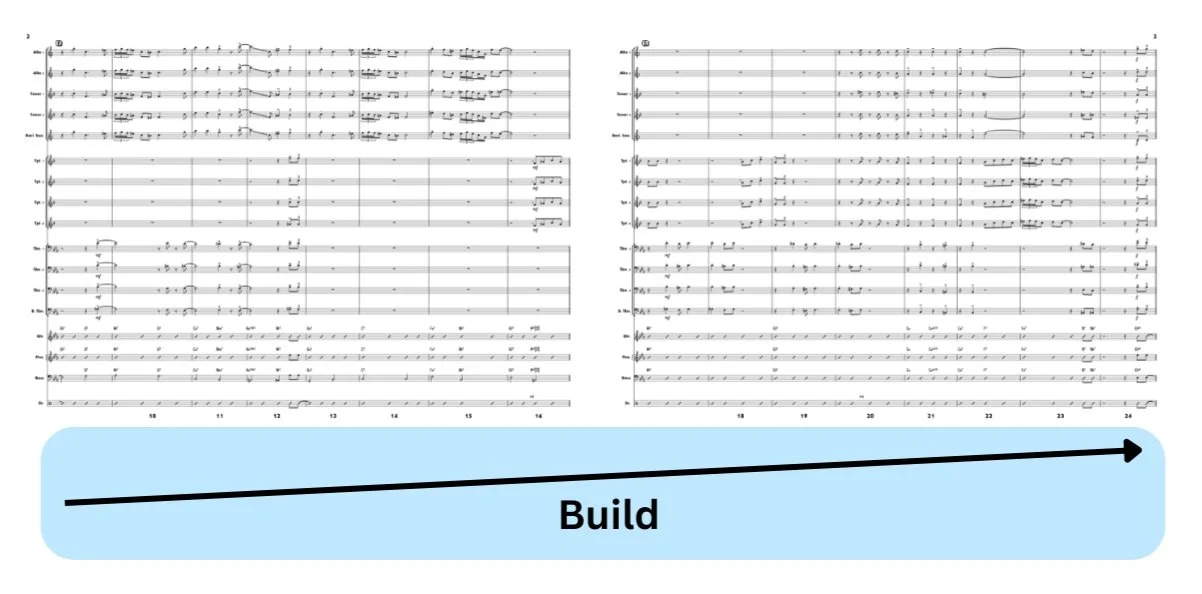

You can also look further than a given phrase and try to map out the contour of a given section. So often scores just have a given dynamic mark for 8+ bars but if we were to take that literally it would generally make the music plateau. Instead, look at the direction of full sections and work out how it all slots together. From there you can then go backwards and see how each individual phrase within a section should be approached.

Once you’ve established the sense of direction in the music the most challenging part is getting the band to convey that. In my experience you should lean on exaggerating everything. It’s so much easier to get musicians to dial back a phrase or section once they’ve nailed it than it is to get it there in the first place. I always tell my bands to overdo it until I tell them it’s too much and in almost all situations they still don’t go far enough. You’ll be surprised how quickly approaching a score in this way will make the notes jump off the paper. Remember, you’re making music not reading it, so lead by your ears not your eyes.

Dynamics

With direction and contour established it’s easy to see that there are actually more to dynamics than the simple p-f system we use in Western music. While dynamic markings are a great starting point, they are far too simple and don’t represent the full extent of the dynamism found in everyday life. One of my favorite examples of this is how the Basie band approached playing softly. Instead of just saying let’s play pianissimo, what they would do is sit in the room without playing a note and focus on the low hum of an air conditioner or some sort of appliance. They would then say that at their softest dynamic they should be able to hear that hum on top of their playing. Whether they actually could hear the hum is another story, but the intent behind playing that softly created a more realistic idea of dynamics, more so than simply reading a marked pp on the music.

Another way of thinking about dynamics is that not every mezzo-forte is the same, even if they are in the same chart. Dynamic markings give the illusion that volume is mapped strictly, however volume is far more fluid and can’t be represented accurately by a couple of symbols. For example, if a musician played a crescendo between a mp and mf marking, they’d show a range of different volumes that exist between those two markers. However, how can we access any of those options when we simply mark the music as either mp or mf? That’s why we have to loosely interpret the dynamics written in a score. They offer a good starting point in relation to the rest of the music, but what exactly an mf is in one context may change and we should be able to interpret it accordingly.

Articulations & Phrasing

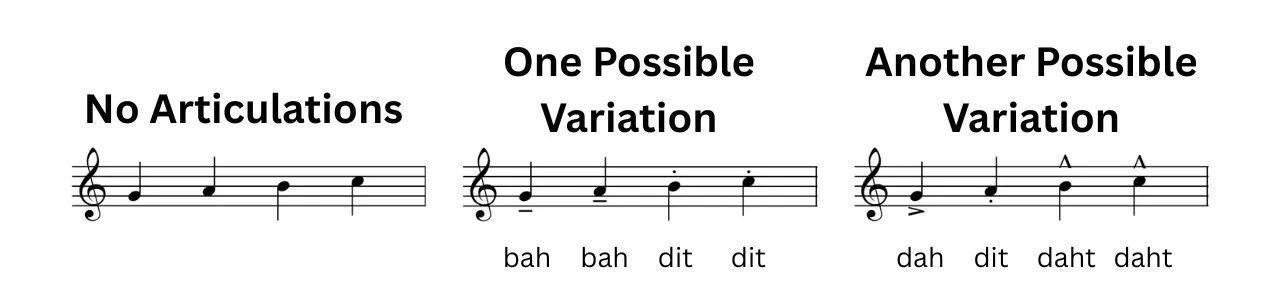

Outside of dynamics, another way we can help transform the music is through phrasing and articulations. It’s so easy just to interpret every note legato (the standard approach in jazz) but that is just one option among many. Unless the articulations are clearly marked, you’ll need to go in and make sure you have a clear idea of how you want each note to be articulated by the band. While this can be overwhelming to begin with, the simplified approach is to think about whether certain notes need to be short or long. From there you can think about if they need to be accented or not, and that’s it.

One way I go about dictating the articulation of a note is by singing the phrase and experimenting with different articulations. It only takes a few seconds and usually I’m able to rule out a number of options pretty quickly. If I’m ever unsure, I just take both options to the band and see what works the best. For staccato (short) notes I use the syllable dit, for tenuto (long) notes I use bah, for accents (accented long) I use dah, and for hats/marcato (accented short) I use daht. From there you need to make sure the players know what articulations you want and again the easiest way to convey that is simply by singing the phrase. Don’t worry I have terrible pitch, all you need to do is be confident and sing the same fixed note on all of the rhythms for them to get the necessary information.

In addition to articulations you also have embellishments such as scoops, doits, plops, falls, and turns at your disposal. These really help shape a phrase but are generally used sparingly. Each one adds a different type of flare to a line with scoops and plops generally happening at the start of a phrase while doits and falls come at the end. I like to think of each of them as a way to bring just a bit more attention to a certain moment. They aren’t always appropriate so be mindful of the situation before you start throwing them around.

Zooming out slightly, another way to interpret the music is by how you define a phrase. Sometimes a phrase is dictated by a phrase mark but often it isn’t, which can be rather ambiguous and allow for some level of influence from us as conductors. Depending on where you dictate the start and end of a phrase you can change how you might interpret the direction and intent of the notes. As a result, the same couple of bars can sound completely different and push the music in completely different ways.

It can be hard to know exactly the right way to articulate and phrase, but over time you’ll start to see how others have done it as well as work out various personal interpretations that you like. All I can suggest is to go out and experiment and as you do, try to be mindful of how the music changes and why you might like or dislike a certain approach. That way you can go away knowing exactly why a certain approach worked and which ones to avoid in the future.

Cleanliness

Although intention is a major component to making music, arguably more important is that the musicians are able to collectively execute that intent as an ensemble. This makes the music come alive and feel unified, and to be honest, is one of the best parts of playing in any sort of band. Fortunately, it is pretty straightforward when it comes to achieving musical cleanliness. Generally I don’t focus on knowing the music as that is something musicians should do in their own time. Instead what I’m talking about are the elements that give the impression that everyone is working together. For me that mainly comes down to entries and cut offs.

While we’ve already looked at these from a conducting standpoint, this section is primarily focused on how to actually get the musicians to execute them effectively. We’re in luck, because both are relatively simple. To have a clean entry it comes down to being prepared. So often musicians only engage a beat or so out from a given entry and the result is that some people simply get to the note slightly delayed than others. As this mainly impacts the horn section, the easiest fix here is to make sure everyone breathes together a number of bars prior to the entry. Not only will this get everyone to engage earlier, it will have the secondary benefit of improving tone and having a more consistent sound across a section. Every situation will be slightly different but leaning on the side of being more prepared for an entry will generally lead to cleaner results.

This idea also extends to complicated passages where it can be easy for a section to feel like a number of individual players and not a unified front. Although this won’t fix the inability to execute a given line, one way to make it feel slightly cleaner is to pick certain target notes to focus on. Similar to an entry, players can prepare ahead of time to make sure they nail those particular notes instead of focusing on every part of a tricky passage. You’d be surprised at how effective this is and I’ve seen a number of pro players do this with the audience being none the wiser.

On the other end of the spectrum we have cut offs. For some reason there is always a sense of ambiguity with long notes where players don’t seem to know where to release their note. As a result, you get a staggered ending which is quite unsatisfying and diminishes the overall quality of the music. To combat this you need to be clear on the exact note duration. Everyone playing the held note should know the precise cut off point and then count while holding the note. It really isn’t that difficult but is highly effective and will make the band feel more unified.

Part Hierarchy

Now that you’ve got the parts sounding musical, it’s time to start understanding how to organize them with one another. Not every line is equal and it is up to you as the director to choose which line is more important. One way of looking at it is to consider yourself as a mixing engineer and as you raise or lower parts you are changing the overall mix of the band. You get to decide what the audience should focus on. While the concept is quite simple to understand, in practice there is a little more nuance needed.

As there are so many instruments within a big band the best place to start is by understanding how each horn section works individually. Traditionally, big band repertoire is built around the lead instrument carrying the most important line with the others in the section playing a supportive role. As a result, the lead instrument will naturally need to be more prominent compared to the others. However, that doesn’t mean that the inner parts should be completely absent as they are necessary for a section to produce a full sound.

There are some cases though where the lead instrument of a section may change, with one of the most common reasons being due to register. As instruments enter their higher register they naturally project more, meaning if you have an instrument in a low register alongside one in a high register you’ll naturally hear more of the second instrument. Generally speaking, the only place where you will need to be aware of this in a big band setting is in the sax section as they are the only horn section with mixed instruments. The way it commonly plays out is when you have a true unison line, in which case the first tenor chair becomes the true lead of the section. It can also take place when there are doubles like clarinet and flute being used too. In these cases it is possible to have some balance issues as traditionally the first alto chair is the natural lead of the section. To combat this you will need to make sure that the section is recalibrated to know who is playing the lead and support roles.

Other than register, sometimes the music is written in such a way where an inner part is actually considered the true lead of a section. This doesn’t take place all that often, and when it does it is usually only for a phrase or two at a time. However, almost always it isn’t indicated in the parts. In some cases it is easy to locate, such as the lead trumpet line being put in the trumpet 2 part, in which case you can hear that the first trumpet is now being pitched below the second trumpet. But in some cases, such as in instrumental features, the featured instrument may be joined by a section which is voiced above them. The only way to be aware of this is to know which line is playing the melody and to prioritize them over the other parts.

Once you’ve established the hierarchy within a section, you can then start mixing the horn sections together. If everyone is playing homophonically, the section in the upper register will generally become the true lead of the horns. Most often the trumpets take this role, but in case it is unclear, you can look at the lead instrument lines (trumpet 1, trombone 1, alto sax 1) and see which out of the three is playing the melody. When in doubt, experiment. You only have three options in this case and it will be pretty easy to work out which section you like being the most prominent.

Now if the sections are not playing homophonically things get a little bit more interesting. You get to decide which lines should be prioritized over others. A lot of the time this means bringing out the section with the melody, however it is always dependent on the context. What you need to do is analyze each section and understand the role they are playing. For example, maybe the saxes have a melody line while the trumpets have hits and the trombones are playing pads. In this case, the most interesting section would be the melody as both brass sections have supportive roles that don’t necessarily bring too much to the table. Every situation is different but if you go in with an analytical mindset and can see how the music is functioning, it will give you a better idea of who to prioritize.

This approach can be taken a little further and is applicable to music where certain instruments are operating independently from their given section. While it may seem more complicated, all you have to do in these cases is understand how each line is operating in the scheme of the overall music. Maybe the second tenor and the third trombone have a little countermelody which needs to be brought out as it takes place while the melody line is holding out a long note. Maybe a flute is doubling the trumpets and should be treated in a similar manner to them. Every situation will be different but the approach to helping them all be heard and balanced is the same.

While these methods are great for balancing the horns, it is a bit less clear when you start trying to apply them to the rhythm section who often play a different role in the context of a big band. The truth is, in almost all cases the rhythm section is playing a supportive role and is never the most prominent part of the band. As such, they should be present but never command the same sort of attention as the melody. Of course there are many exceptions to this, such as drum fills which set up the band, melodic interjections, as well as times where the melody is actually given to a rhythm section instrument. You’ll have to use your intuition when these moments arise as to how they should be balanced alongside the rest of the music but they will allow for the rhythm section (or certain rhythm section instruments) to stand out for a brief moment. In terms of balancing the instruments within the rhythm section, fortunately they each have such a distinct timbre and role that they often naturally support one another when played at the same dynamic. If you feel the rhythm section isn’t balanced, the best way to approach the situation is to make sure each player can hear the other rhythm instruments while they are playing, that way they won’t overstep with their own part.

With all of this in mind, we need to take a step back and start thinking about balancing the entire band. We now understand how to balance each of the sections, specifically the horns and the rhythm section, but it’s time to look at combining them. Unfortunately, so many people don’t do this correctly and end up having an unbalanced band. It doesn’t matter how great each of your sections sound individually, if the full package doesn’t come together it ruins everything. To do this successfully, the band needs to be balanced to the quietest instrument. If you are playing acoustically, that is either going to be the acoustic guitar or bass, and with amplification it will most likely be the piano. However there are moments where it may change to a flute or harmon mute trumpet depending on the situation. Everyone needs to be aware of the quietest instrument so that they can gauge their own levels accordingly. An acoustic bass’s loudest sound is vastly different to a trumpet and if the trumpet isn’t aware of how their playing can impact the overall picture, you’ll end up with an unbalanced band. This obviously applies to every instrument in the band and not just the trumpet.

Ironically, in acoustic situations it is often the rhythm section instruments which are limited dynamically, whereas when they are amplified it is far easier for them to squash everyone else. You will need to handle amplification with care. Don’t simply let the players gauge where they want their volume to be set, they aren’t out the front of the band and their actions may have serious consequences for the entire ensemble. The key to having a well balanced band is by having all of the musicians being aware of one another’s parts and where their own lines sit in the context of the entire band. From experience, the best and quickest way to bring attention to everyone’s parts is simply to have a group discussion. As you have access to the score, you can lead the discussion by bringing attention to similar parts and what to prioritize. You can then run certain sections and have the musicians listen for specific parts they may have been unaware of earlier. In an ideal setting, the musicians would do this right from the get go, but as we all know, it is far too easy just to focus on our own individual parts regardless of how experienced we are.

Balancing an ensemble is an active responsibility from everyone. However, you are the one in front and have the best vantage point to both hear everything and communicate with everyone. Just like driving a car, sometimes everything will run smoothly and you’re able to cruise along, but also quite quickly something unexpected may happen and you have to be ready to jump into action and react accordingly. Try not to disengage and know that while you are responsible for keeping time, cueing, and everything else, you also need to be keeping your ear out and trying to balance the ensemble throughout an entire chart.

Rehearsal Productivity

So you know the basics of conducting and how to bring a score to life, well now it’s time to look at the actual practicalities of running a great rehearsal. Something which is essential to being a great conductor as it is the only time where you get to practice the music ahead of a performance. Like everything stated here, there is no one way to go about having a productive rehearsal. In almost all circumstances you will be faced with a different context, whether that be different people, different locations, or simply the fact that every day is slightly different from one another. As such, we have to be adaptive to our environment and use our best judgement in the moment in order to have a successful rehearsal, but there are a few methods you may want to be aware of ahead of time.

The first port of call is to have an agenda or plan for every rehearsal, something you want to achieve with the time you have. You can be as detail orientated as you want, but simply having some kind of agenda will help inform you how to use your rehearsal time effectively. We all know that musicians love to socialize, so if you are coming into a rehearsal space unprepared then you are setting up a situation where everyone will likely just catch up with one another more than play their parts. In the past what generally informs how I use the time is the repertoire I would like to cover in the time allotted. You should have a pretty good idea of what parts require more time than others, as well as the general duration of each piece. I don’t usually set strict time allocations to each piece or section, but I will think about them in terms of priority and make sure the more urgent tasks are dealt with at the start of the rehearsal.

From there, I like to be as clear as possible to the musicians about my agenda so that they have a realistic expectation of what we need to cover. That way everyone is in the know and we are working together instead of it being just me with a plan. Communication is key for rehearsal productivity and everyone should feel comfortable discussing issues as well as receiving critique. If you’re able to foster such an environment, it will be pretty easy to achieve almost anything you want out of the band as long as you have the required time.

Finally, on a more practical note, rehearsals should be specifically spent on areas that can’t be worked on outside of the rehearsal space. What I mean by that is that the musicians should not be running individual lines that they could practice at home. Instead, focus on areas like working as a section, balance, blend, and really anything that requires multiple people together. Rehearsals should be about crafting the music, not about note crunching.

How you go about working on specific ensemble moments can vary but there are two approaches I’ve found to be the most effective: running full sections and running small passages. In order to get an understanding of how the music works as a whole it is necessary to play large chunks of the music without stopping. The main purpose of this is twofold, to help the players understand how their parts work in a larger context and to get more comfortable with performing the piece as a whole. It is likely they may still make mistakes but remember the point is less about small issues and more that they get a feeling of the whole piece. From there you can isolate smaller passages to work on specific points which you may run a number of times. Personally, how much you focus on smaller passages is more dependent on the level of musician you are dealing with and in professional circumstances I’ve often just talked to the band about the changes I want and then on the next pass they’ll make the required changes. Of course this is unrealistic for amateur musicians who need the extra time on their instrument to really understand how to apply the changes discussed. I should also mention that my go to rule is to only really focus on one improvement at a time, that way you can quickly address an issue, resolve it, and then move on to the next without overburdening the musicians.

The Responsibilities Of The Job

You may remember the story I mentioned earlier of the tragic performance that was compromised due to the conductor not adequately signposting. Well there’s a little more to the story that I think you should know. The person in question had come to me a few months earlier with the idea to have the youth band perform Stan Kenton’s Cuban Fire suite. An ambitious goal but I was happy to indulge as I had trust in the conductor and he had a proven track record for decades with other similar ensembles.

For those unfamiliar with the suite, the entire concept of the album combines elements of Cuban music with the big band tradition. What this looks like is a mixed instrumentation which is built on a core big band. Instead of just having the standard 4 trumpets, 4 trombones, 5 saxes, and 4 rhythm, the suite calls for an extra trumpet, trombone, tuba, 2 french horns, and most importantly a full four piece Latin percussion section. That’s a 26 piece band! The music itself is extremely impressive but to pull it off requires a considerable amount of knowledge not just about traditional big band music but also Cuban musical culture. Without going into too much detail, in order to feel confident leading such a band through that material you’d have to be versed in about a dozen different non-Western musical styles (in addition to the more common swing styles), know how to communicate with percussionists who don’t typically play in a big band setting, as well as feel comfortable with more orchestral instruments such as tuba and french horn. To throw even more variables into the mix, remember this was a youth program and the majority of the performers had no professional experience and would require a lot of assistance from the director, both with their individual parts and also in understanding the context of the music they are playing. No matter which angle you look at, the project was very ambitious and required absolute dedication from the director.

As someone that has spent years studying Cuban music, reading the literature, listening to the music, transcribing, and also learning how to play many of the instruments, I can guarantee that there are only very few people in the entire world that have the entire set of crossover skills to single-handedly direct this project. Unfortunately, at the time I was far too optimistic about the director I had hired and believed he would be able to fill the gaps in his knowledge in time. Something which definitely didn’t happen unfortunately. As a result the music suffered.

Earlier I highlighted their inability to signpost but the core reason behind this was because they simply didn’t have the necessary skills to handle the situation and in the moment they were most likely overwhelmed. In order to get a handle of the situation the director needed to communicate with every musician in the band in a way which they could understand. That meant knowing the terms that the percussionists used and how they may differ to the ones the rest of the band were using. Unfortunately, they hadn’t done their homework and didn’t have the necessary skills to control the band in an emergency situation.

The reason I wanted to unpack this story a bit further is not to bring shade to that particular director but more to highlight how much responsibility you have when you stand in front of a band. So often bandleaders are picked out of convenience due to the situation at hand. Almost all of the school bands I’ve guest workshopped with have had conductors who are underprepared and often are just there because they had the most knowledge on jazz out of the faculty. Other times the person has volunteered, not realizing what they are signing up for. Unfortunately, no matter how a director is appointed, once in that position they have a certain level of responsibility to uphold.

To me, if you want to be a great band director you must understand everything you are asking your players to do and be able to explain it in such a manner that they can see why it is important. You don’t have to be proficient on every instrument, but you do need to be aware of the quirks of each instrument you conduct, otherwise how are you going to know what to say when you hear something problematic? What I’m really talking about is having empathy to relate to the issue and then having enough understanding to offer solutions. I can’t play trumpet but I know what it feels like to try and squeeze out a high note so I can relate to them when we discuss shout sections. I also know certain possible approaches which may help them play those notes, such as certain mouth shapes and breathing approaches. The combination gives me the best chance to help the trumpets under my direction and more importantly help us create better music.

In addition to individual instrument qualities, you should also be aware of how they operate contextually. For example, if you are playing the music of Count Basie, it is important that you know how that impacts all of the instruments in the band and what is needed to capture the essence of that music. As you can imagine, this can change drastically from piece to piece but it is essential if you want to do the music justice and tap into the big band tradition. What you’ll find is that depending on the context, each instrument may have different terminology that you have to be aware of. For example, if you were to have a Latin percussion section you’d not only have to be well versed in the rhythms and patterns they had to play for a given piece of music, you’d also have to know how to talk with them about it. In the case of the band director who tried to lead the band through Kenton’s Cuban Fire suite, they didn’t know that most Latin percussion sections don’t read music and must be instructed where the hits, breaks, and changes of groove are. When trying to communicate this information, they also didn’t understand the correlation between certain styles and rhythms for each instrument, ultimately leading to a lot of confusion and one reason why there was such a major trainwreck.

While the youth program story is definitely on the extreme side, it really highlights how bad a situation can get when the conductor doesn’t have the required knowledge for the music at hand. So often directors hear recordings that they fall in love with and think “that’d be perfect for my band,” without ever considering whether they have enough knowledge required to pull it off. My general suggestion is that you should only put music in front of a band that you understand. Not just from a personal point of understanding what is going on but also from the standpoint that you are so well versed in what is going on that you can show others how to achieve the results you are looking for. Far too many people expect so much out of their ensembles when they simply don’t put that expectation on themselves, and that isn’t fair for the musicians.

If you end up in a situation where you have to get through repertoire that you maybe don’t feel so confident about, be transparent. No one is perfect and we all are learning. No matter who is in the band, everyone can relate to the feeling of not knowing. However, as you are responsible for the band you then have to follow through and do your homework if you want to keep playing the piece. What you’ll find is that by being transparent and putting in the work, you’ll gain a lot of trust and patience from the players, which is far better than any other situation.

When I started out directing bands I literally knew nothing about anything I’ve mentioned on this page, yet I was still standing in front of big bands trying to make it work. Everyone starts somewhere and it is quite unrealistic to expect that you’ll know everything needed for a perfect performance when you’re just starting out. We are on an ongoing journey and no matter how much you understand, there’s always something more to learn around the corner. Just make sure you take responsibility for your actions and try your best to service the music and band in a positive way. Whatever reason that has led you to direct a band, I can tell you that you’re going to do a great job because you have taken the time to look for resources on how to be a better conductor. To help you out just a little bit more, below you’ll find a list of values that make a great leader. These are applicable to situations outside of big band directing and by no means are an exhaustive list, they are just what I’ve found helpful to focus on so far in my journey.

Passionate

When you meet someone who loves what they do it is apparent in every part of their life. The best big band directors are passionate about the music they are conducting and as a result often the musicians that follow them love the experience that much more. Your mood is infectious so try to remember why you chose to be a conductor and lean on that in the tough times.

Honest/Trustworthy

If you want people to follow you, you have to tell the truth and be honest with your responses. People can tell if something is off and if they start to lose trust in you, it’ll negatively impact every other aspect of your relationship with them. Why would a musician follow your direction on the band stand if they didn’t believe you could help them? And if they did decide to follow you, it might lead to resentment which is much harder to fix.

Responsible

A good bandleader hones up to their actions and takes responsibility for their mistakes. When you stand in front of a band you aren’t just waving your arms around, you are the leader of those musicians and as such you are responsible for steering them in the right direction. As such, while you may get a lot of the glory when things go right, you also are entirely responsible for anything negative that might happen too. It’s part of the job and you have to be willing to take on that responsibility if you want to be successful.

Reliable

No one has ever complained about someone coming through when needed but as soon as someone lets another person down it gives the impression that they are unreliable. A great leader shows up on time and sticks to what they promise. Most of the time you won’t get any recognition for being reliable but if you go the other direction you will start to receive the wrong kind of attention.

Committed

Why would you follow someone who wasn’t invested in your ensemble? One of the easiest ways to take the heart out of an ensemble is by showing how little you are committed to them. Every now and then you may need to prioritize other things, but if you have made the decision to be a bandleader then that comes with the commitment to the position and the ensemble. Show that you are committed to the musicians and the music they are playing and it will model the sort of behavior you want out of them.

Intentional

While playing music is a very enjoyable experience we need to make sure that we are intentional with our approach to leading. The position means that more people depend on us and as a result they will pay more attention to our actions. Make sure you know what you want to do, how you’re going to go about it, and most of all why you want to do it. That way your intentions will always be clear.

Patient/Supportive/Kind

You never know what someone else is going through, and even if you do, you aren’t that person and don’t know quite how it feels. As such, the only real way of talking with others is with kindness. That doesn’t mean you can’t be honest and talk about difficult topics, but it does mean that you treat them with respect and model how you’d like to be treated. This is especially crucial in younger ensembles. It never hurts anyone to be kind, patient, and supportive.

Inspiring

Finally, if you follow through with all of the values listed here as a result you’ll likely be seen as inspirational. In a rehearsal space you’ll often come up against people who don’t want to do what you’re asking or simply ignore your directions. Most people try to offer some sort of manipulation in order to get these people on their side. To be clear, I don’t mean they are trying to manipulate them maliciously but instead through means such as offering rewards for certain behaviors. Other times it can be a bit more negative where they may scream or get angry as a way to try and coerce you to follow them. Either way, the end result is never good.

There are three specific times I have been screamed at openly in front of a full band. Once as a 15 year old in my first big band rehearsal at high school, the second as a 20 year old in an improvisation class at university, and third as an adult working in a professional capacity as a musician on a cruise ship. All three times never made me want to work harder and had the opposite effect where I wanted to run away from music entirely. I can still remember each of them clearly as if it were yesterday.

Unfortunately, that behavior instilled in me a subconscious image of what being an educator and band director looked like and when I started my youth program, many of those negative characteristics came through in my own band leading. Only by removing myself from that situation, spending more time researching effective leadership techniques, and realizing how I was simply regurgitating the aspects of my musical journey I hated, have I since realized how damaging that approach is. If you ever find yourself in a position where you think it is okay to verbally yell at someone as a leader, the best option is to remove yourself from the position because you are simply making the situation worse even if you think it is the right thing to do at the time.

While this is an extreme example of manipulation, all examples never work out in the long run. You may get immediate results but it usually comes at the expense of longevity and long term gains. Unfortunately, it is so easy to get hyper focused on one rehearsal or one particular moment and then lean into manipulation so that you can more quickly hear what you want to happen. In all of my years, the only way to truly get the results you want is to inspire those you lead to want them too. Unfortunately there is no cut and dry way to inspire but from what I’ve seen in my life is that if you pursue your dreams, you’ll show others that they can too. The trick is to channel that as a director and get the musicians excited about the music they are creating and the only authentic way of doing that is by being excited about it yourself.

Remember that music is meant to be enjoyable. If you aren’t enjoying the process of making music then you may need to reevaluate the situation and come back once you start feeling excited. Look at what got you into music in the first place and accept that it may take some time to find that place in your heart again. But once you’ve found it, there will be no stopping you and you’ll inspire all of those around you.

The Takeaway

Bandleading is a big job with so many moving parts. It is in one way completely unique to every other aspect of music but at the same time somewhat familiar. The only way you are going to get comfortable with it is by throwing yourself at conducting and learning as you go. Try to accept that you won’t know everything. I mean I’ve been doing it for years and still don’t feel like I’ve mastered the craft at all. Hopefully the information on this page will help you get more comfortable with the role a little faster than it took me and if there is one thing to walk away with it’s that there are no fixed rules when conducting a big band. Do what feels right to you and those you’re directing and go from there.